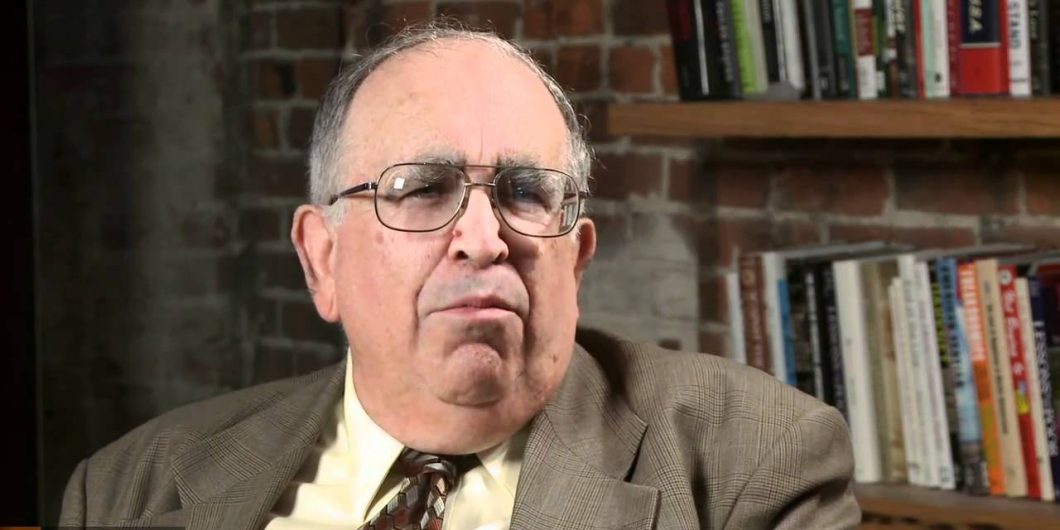

Farewell to a Great Shakespearean

America’s greatest Shakespearean, Paul Cantor, is dead. He was the author of Shakespeare’s Rome: Republic and Empire (1974) and Shakespeare’s Roman Trilogy: The Twilight of The Ancient World (2017), the most important works of criticism on the poet who has been of greatest importance to American history and to the education of the American people. A serious study of his interpretations of Shakespeare—and he had many other essays and volumes covering the other plays—would by itself be an education fit for any American who wishes to understand the inheritance of this greatest of modern republics and the drama of political freedom since Rome. Conservatives especially should honor Cantor, because he was an unstinting benefactor where we are most in need of help: education.

Cantor was born in 1945, a child of the American mid-century. America was then far more prosperous than the rest of the world, had achieved a tremendous and we can almost say blessed victory in WWII. Accordingly, it was far freer and less riven by mutual hatred than it is now, and had a confidence that today cannot even be imagined. This opened it to all the greatest achievements of the spirit that were then available. Cantor accordingly studied Austrian economics with Ludwig von Mises in New York City and Straussian political philosophy with Harvey Mansfield at Harvard. These twin concerns with economics and politics, with greatness modern and ancient, shaped his writing for the rest of his life. As an American and as a student, he was not the peer, but the friend of the greatest thinkers, and he loved freely Plato and Nietzsche, and much more in the history of philosophy.

He was at the same time a fan of TV, including watching reruns of old movies and the horror stories of Universal Pictures from the 1930s, which brought to America the English myths of the problem of good and evil and the connected problem of immortality—Frankenstein, Dracula, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and the stories of H.G. Wells. He was a fan of Wagner, too, and he wrote with fascination on the last attempt in Europe to bring back mythology and give the Germans something that cannot be understood in America: a national, cultural, and political project of education of the passions that started from medieval fairy tales that were older than Christianity.

I want to say also in what way Paul Cantor was childish. If you watch him lecture, you will notice how much he enjoys the troubles he is studying and trying to articulate—how funny he thinks the human situation essentially is. This spirit has seen many students through the terrible stories Shakespeare chose as especially fitting for a modern education. Cantor learned to love the ancient heroes, but also the modern ones. In every attempt to attain human greatness, he found something to learn; and he tried to present intellectually the different moral possibilities—since he found no man completely excellent—but instead tried to see the conflict and competition between the various excellences that show our nature, our powers, and the good we seek. Education awakened in him the taste for greatness even as it kept him always reading, watching things, and involving himself in the public debates of his time. He became an adult in a certain way that is now hard to believe, and about which we have accordingly become silent—his judgment was worth hearing in most cases he cared to offer it, and he knew himself in his duty to offer his judgment generously. He therefore improved everyone who had the good fortune to meet him, because he wished to improve himself without any selfishness, but always as a child going to study amazing matters, without any respect for blind prejudice or arrogant contempt for asking questions. In becoming aware of the world around him, he became aware of his own nature, and therefore of the human longing to understand everything.

It is not impossible then to imagine a school built with the help of his many insights, since they are written down and can help us remember and come into possession of our civilizational inheritance. Perhaps this could include some of his students, who have achieved a certain deserved prominence in academia. It is not impossible to imagine how others of his students, out of gratitude and a wish to rise to a comparable generosity, would donate to such an enterprise. It is possible, it is indeed uniquely American, to associate in order to remember the achievements and to achieve anew the learning and experience the delight he shared with everyone willing and able to have such conversations. It is a kind of freedom of the soul to be able to do this, and it is at the same time a necessity of civilization—education in the strict sense. To honor the man would be not only to remember how he benefited his fellow Americans, but to be benefited by him and thus to remember that man cannot be swallowed up by the grave, since the soul is tied up with love and learning. Let his many friends remember themselves through this duty and be friends to each other and to their posterity—this is Paul Cantor’s true legacy.

He was the best that mid-century liberalism could produce, a unique combination of the popular and the high-minded.

All who wish to learn from him can find, along with his books, his other writing online on a website a friend recently made for him. His many lectures on Shakespeare are available on YouTube (Shakespeare and Politics), as well as his many conversations with Bill Kristol. I had the privilege of reviewing his last book for Law & Liberty, Pop Culture and the Dark Side of the American Dream: Con Men, Gangsters, Drug Lords, and Zombies. I know he had a high estimation of his worth and I do not blush to share with you his opinion that he was even better as a lecturer than as a writer. In my opinion, this is true, because his expertise always led him to seek a way to present to others all the clues he was puzzling over and the paths he was wont to take in his own studies. He was most himself when he led those who chase after the same things—the soul, the virtues, and the elusive nature that seems to us always a welcoming home.

I end with a personal note—Paul Cantor was a friend to me, having generously accepted to sit on my board at the American Cinema Foundation. He joined me for long podcasts on cinema, modern mythology, and TV shows; and encouraged me in my writing work, which is a humble attempt to follow in his footsteps. He was as much a friend in all that you would expect of a man with a broad and deep humanist education, from comparing notes on the European cities we both loved, to conversation on the greatest problems of human nature illuminated by tragedy and comedy. I have on occasion grieved that he was not more celebrated, since so many people could be both charmed and benefited by his humanity, and I felt deprived of his company and conversation because high-minded educators receive little respect in our democratic age and accordingly are seldom free. But he never showed any such concerns himself. Instead, he was always looking forward to the possibilities of education opened up by digital technology, since he was always a friend of the American people and of all lovers of learning, and only wished to see them liberated from prejudiced authorities or institutions that do not respect the freedom of the mind.

He despised, with eloquence and charm, the corrupt academia of our times and the even more corrupt publishing, these things that have made a grotesque caricature of a liberalism once noble, dedicated to Enlightenment, friendly or at least tolerant of scholars like him. I saw in his contempt a proud freedom, cheerful that he did not fail where others did. No one who loved him could fail to become as light-hearted, reassured by any touch of greatness, and armored against decadence,

With him dies an entire way of life, since he was the best that mid-century liberalism could produce, a unique combination of the popular and the high-minded, one of the rare men who was as much at home in Shakespeare’s articulation of the history of our civilization as in the worries and amusements of the ordinary people among whom he grew up. For him, patriotism was never indifferent to the attempt to scale the heights of the spirit; he did not see limits in the American way of life, but freedom. He gave constant evidence that friendship is a higher thing than justice, since it involves no desire to punish and no shame. He taught all of us who counted him a friend how to love the works that give access to human greatness. In owing him gratitude, we finally only wish to live up to what he saw in us. He was happy while teaching tragedy, and if I have said anything worthwhile here, it is only because I am happy in remembering him.