In Summer 2020, Vox published an article celebrating the acronym BIPOC, at that time suddenly “ubiquitous in some corners of Twitter and Instagram.” Focusing on the SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective, the article heralds BIPOC as a term of solidarity countering the “minoritizing” of certain oppressed groups. At the very bottom of the Vox piece, a correction is found: “An earlier version of this article defined BIPOC as standing for ‘“Black and Indigenous people of color.’” It stands for Black, Indigenous, people of color.”

We can laugh when purveyors of new liberatory speech get into a muddle and end up excluding those they had hoped to champion. The amusing irony of the situation flows from the fact that toying with language is serious stuff, going to the quick of our efforts to live peaceably. Words are not all there is, but we express belief by them: “We hold these truths to be self-evident.” Language mediates our common life. It is delicate.

Liberalism has its origins in modesty, in the effort to find a political form that might allow mutually exclusive passions to be indulged without corroding the capacity of people to live together. Instead of civil war and cleansings, liberalism developed a neutral establishment to free other spaces for the unencumbered play of reverence, argument, and quirky pastimes. Emergent in seventeenth-century England, it required communities to commit to forbearance and forsake, as Michael Oakeshott points out, any politics matching the Puritan phrase “commands for truth.”

When the use of BIPOC exploded in summer 2020, Vox did better than many blue checked Twitter users who thought the term meant “bisexual people of color.” This misnaming called for clarification from the New York Times. They turned to a Ms. Gabby Beckford, “a travel content provider,” to educate us: “If you’re talking about black people, don’t say BIPOC. If you’re talking about overpolicing in the United States, you can say black people. It can seem lazy, but if you’re talking to people of color in general, compared to the white experience, I think you should say BIPOC.”

Likely none of us need to be schooled by someone the New York Times plucks off the internet, but universities, mechanics’ shops, air traffic control, accountants, and the courts all require precise speech. The importance of names is highlighted at the start of the Bible when God invites Adam to name the animals. A deft use of words is basic to the contracts of commercial civilization. There is nothing foolish about fretting over names, or deferring to authorities learned in their use, but liberal politics requires frank assessment of their polemical value, the pretension of their reach, and the ethos they nourish.

Commands for Truth

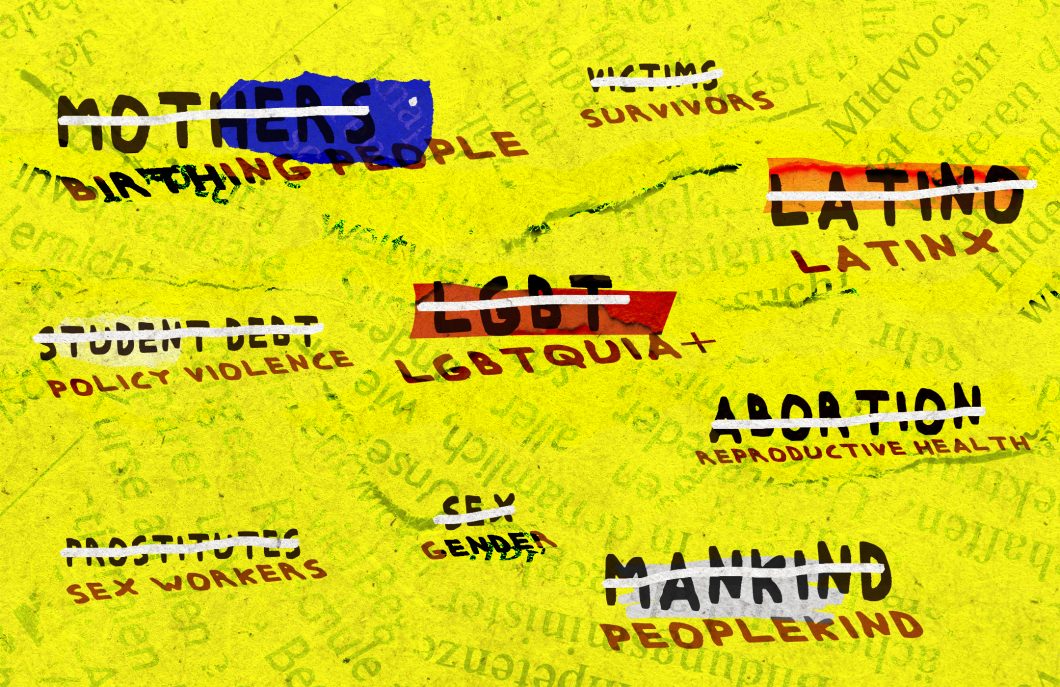

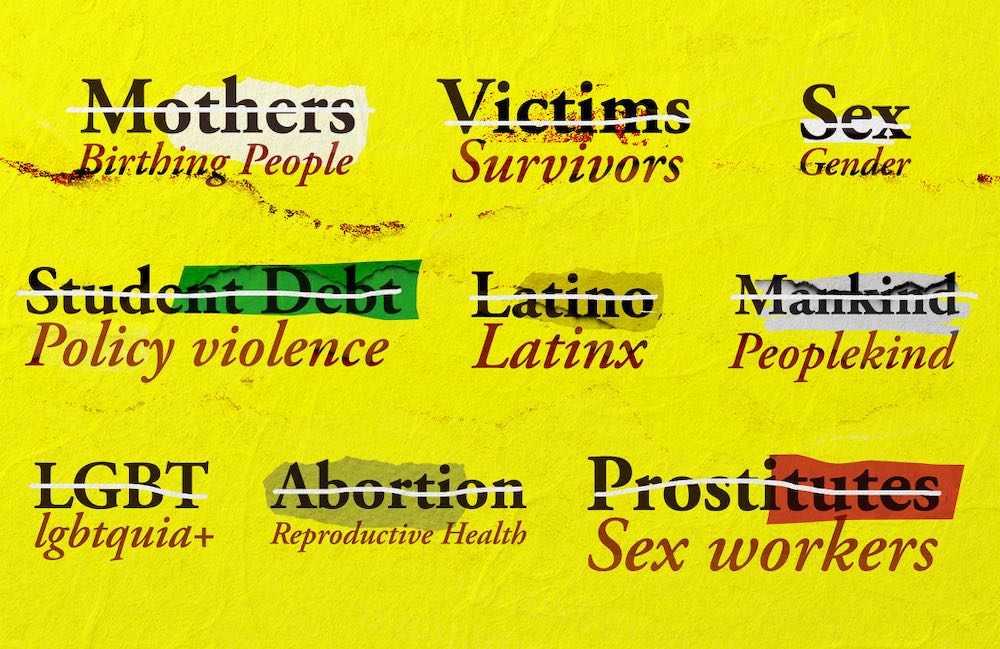

In no particular order, and with no hope of being exhaustive, here are some recently proposed terms for freshening our political vocabulary:

For the left, the polemical value of these changes sits in eroding stratification. Inspired by the Hegelian Marxist hope of dissolving the master/slave dialectic , many on the left aim to eliminate names that hint at inequities of power and standing. Oppression is overcome when hierarchy is gone, reasons the left: those managing the modern state must not box persons into roles in which they might be looked down upon. Our governing institutions must function like a perfectly smooth mirror in which all find equal recognition. Not for the left is St. Paul’s “through a glass darkly.” The left’s lexicon does not tolerate the social refractions and blemishes which are the lot of finite creatures muddling through a recalcitrant cosmos. Hegelian Marxism, as Eric Voegelin observed, echoes the Puritan politics of the Saints of God. Sanctifying language both burns away the taint of past oppression and delivers speech, making it worthy of equality’s shawl.

The left’s new lexicon would have us conspire in the immodest belief that we do not belong to the cosmos, but are free to flit across it, without resistance from its geography or binary structure.

That the Saints are on the march again can be gauged from changes in tone between Sex in the City (1998-2004) and its continuation series And Just Like That, which premiered at Christmas. The original cult show featured four New York white women who, amidst a surfeit of luxury shoes and handbags, pursued their ambitions at work and in the bedroom. In 2022, sanctity is on the agenda. In the reboot, Miranda (Cynthia Nixon), now about 50, quits her position in corporate law and goes back to college to study human rights. Unaware of the “hot house” atmosphere of the contemporary campus, she enters the classroom and immediately makes two mistakes. About to sit on a chair, she is told that is where the professor sits. A black woman enters the room, and goes to sit in the same chair. Miranda tells her it is reserved for the professor.

Watching, you do not need to see the scene play out, for of course the woman entering the room is the professor. In college- and corporate-speak, Miranda’s faux pas is (at best) a microaggression, and perhaps overt racism. The scene segues: flustered and eager to explain why she mentioned the chair at all, Miranda points to a boyish student and says, “he just told me.” Again, predictably, the student immediately retorts, “someone’s quick with the pronouns.”

The writing is obvious because polemical. It is also mischievous because the show wants to blend the two trespasses. Are they equivalent? The first is insulting, betraying a belief that members of a certain race cannot be professors. A skeptical person might think the second an insult to pride only. It is reported that Cynthia Nixon would not return unless the show devoted segments to social justice education. The writing in And Just Like That is nothing like the ludicrous lectures on wokeness from PC Principal in South Park; the modesty built into satire has been jettisoned for the sham clarity of commands for truth.

Inventor of Newspeak, George Orwell complained that “the whole tendency of modern prose is away from concreteness.” He gives the example of government messaging using the term pacification to cynically mask the reality of attacking and clearing out villages. Miranda’s first trespass stems from an ugly legacy of American history, but the supposed second touches on Orwell’s point. The left’s new lexicon would have us conspire in the immodest belief that we do not belong to the cosmos, but are free to flit across it, without resistance from its geography or binary structure. As the Scottish Enlightenment philosopher Thomas Reid argues, the most common elements of language give testimony of organic order. Certainly, we chafe under the rules of the cosmos, but the ancient forms of language concede its sovereignty. There is a difference between demanding names change to reform brutalist inherited attitudes and wanting names to change so all fall in line behind an assured elect inspired by an abstract engineered ideal.

Mother Tongue

Language changes constantly. Very frequently, human ingenuity is responsible. Our speech is enriched by the creativity of writers, rappers, advertisers, comedians, and sports fans. Sometimes language also changes because activists justly require it, and at other times because something fishy is going on. The observer of totalitarian thinking, Hannah Arendt notes that National Socialism was keen on making up new words. The innovations were designed to deflect attention from what was really happening. Rightists manipulate language, as do technocrats. Arguably, our grimmest evasion, masking the killing of innocents by the phrase “collateral damage,” dates to the Vietnam War and was the creation of technocrats tasked with measuring the utilities of military operations. Yet it is the left that has a striking penchant for the rapid switching of terms. The motivation is not to dodge guilt, but to reach across history and transform our standing in the cosmos.

Julia Kristeva is a French psychoanalyst, comparable in significance to Roger Caillois, Albert Camus, and Michel Foucault. She writes:

The human being is fundamentally binary: digesting the good and expelling the bad, oscillating between the inside and the outside, pleasure and reality, prohibition and transgression, one’s self and the other, body and mind. Language itself is binary (made of consonants and vowels…). Thus children gain access to the difference between good and evil at the very moment they begin learning the mother tongue.

The left balks at the use of the term “mother tongue.” Convinced that the family is a core scene of oppression, advanced humanitarianism demands the mother tongue be dispatched. What is lost when we replace mother tongue with “first language”? In light of her psychoanalytical practice, Kristeva argues that children first access language through their mothers. Language is not cold abstract code; it is bound up with the dynamics of family life. Her work defends the claim that the binaries of body, family, speech, and morals are interwoven.

As Aurel Kolnai points out, when the left accuses the rich of being bandits, it invokes an ancient moral binary. Yet, not for the left is the Psalmist’s “you knitted me together in my mother’s womb.” Progressivism’s sanctity demands language be pegged not to the messiness of birth and piecemeal aggregations of family inheritance but to an impatient rush to the deification promised at an “hour you do not expect.” The left’s is a hyper-morality, a self-made production inspired, as Kolnai suggests, by “perfection-visions.”

The term “first language” is proposed for it has the ring of an axiom generating clear directives, able to support a plain and evident plan for moral and political change. Perceptively, Kolnai identified leftists as futurists, their fascination with comprehensive plans a reach for the divine:

The metaphysical core of the concept of social Totality is the concept of Identity; and the postulate of Identity, again, is implicit in man’s pretension to metaphysical sovereignty, his aspiration to be God: for if I admit any entitative “otherness” of mind and will on a footing with myself, if I am aware of any human consciousness and purpose really distinct from my own, if I recognize any valid law and authority over and above my will—and not an efflux and manifestation thereof—I cannot be God.

Mother tongue connotes inheritance, first language, a future where human life is delivered from all “entitative otherness” stemming from our place in nature. Language is an archive of our long and difficult encounter with the cosmos. Fabricating names, the left cancels Creation and ambitiously proposes a transhumanism: not a matter of keeping time with nature, but a thoroughly insular mind-filled venture to plot new words for a new beginning; to have the novum without the ovum, as Carl Schmitt quipped.

Holier Than Thou

Liberal conservatism has always been wary of reprimitivism. Burke and de Tocqueville dwelt at length on the political wisdom of inheritance but rejected reaction and atavism. American life has benefitted from greater tolerance around sexuality and the left’s pressure to remove offensive terms from the nation’s vocabulary, especially around race. Futurism, however, is zealous, as the idea of the microaggression illustrates. David Hume defines modesty as a “dread of intrusion.” The left’s lexicon is a hyper-moralism, for at its core is the sin of presumption. Hume argues that the discovery of minute objects sparked the modern age. Around the time of Hume’s birth, Leibniz reckoned he knew everyone who had a microscope. Hume’s is an inquiry into the implications of the microscope, a contemporary example of which is the microaggression.

Words have become snares, their policing a way to wrong-foot the innocent in conversation. Ours is a shrill age because there is an effort to wheedle out the “malign” layers of the unconscious.

Vox explains that: microaggressions are “the everyday slights, indignities, put downs and insults” of the marginalized. The man who coined the idea says microaggressions are “put-downs, done in automatic, preconscious, or unconscious fashion. These mini disasters accumulate.” So minute are these “mini disasters,” they escape ordinary awareness, only visible to those with a special lens: “People who engage in microaggressions are ordinary folks who experience themselves as good, moral, decent individuals. Microaggressions occur because they are outside the level of conscious awareness of the perpetrator.” Most of us, blithely unaware, need the commands of truth to come to clarity about the hidden engines of our love and hate; indeed, the minuteness of our biases, Vox informs us, “makes them all the more dangerous.”

Words have become snares, their policing a way to wrong-foot the innocent in conversation. Ours is a shrill age because there is an effort to wheedle out the “malign” layers of the unconscious. We have an unholy trinity of presumption, scrupulosity, and inclemency. The left’s presumption is to renew the world, and with it returns the age of scruples. Arguably the greatest discovery of modernity’s micrometer is the unconscious. The contingencies and frenzies of the unconscious are a challenge to the axiom driven renewal plan of the left, which explains why the left’s advanced humanitarianism is unforgiving. The unconscious is “fragmentarily knowable” and cannot be “derived from any all-embracing principle” (Kolnai): it is the very definition of Burke’s prejudice and prescription.

Those familiar with psychoanalysis will guffaw at the absurdity of trying to cleanse the unconscious, but the new sanctity requires scrupulous obedience. The forlorn intrusion into the unconscious stems from suspicion, which explains the moral hounding of cancel culture. The immodesty of the idea of the microaggression comes from a loss of trust, a disappointment in human nature. Hume argues that though benevolence is not the strongest sentiment in our make-up it prevents us, when seeing a neighbor hobble past with a gouty foot, from having a bit of fun and standing on it. The left is not so sure: they suspect that most of us are driven to go out of our way to hurt others. Since our natures are guilty, there is no trustworthy self-evidence, no reliable first-person testimony of innocence. The unconscious is put upon the rack, scruples canceling tolerance, and commands for truth ensuring we speak clearly with one benevolent voice.

Kolnai argues that genuinely religious people experience morality not only as the self-evidence of value and disvalue, but as reflecting a “divine exemplar, codifier and guarantor of virtue at least in the background.” God is not the obvious center of our moral experience but is there as an underlying partner in the moral. There are people holier than thee and me, but those who go hunting for faults are not among their number. In the wake of zeal are surveillance and suspicion. The amplification of the guilt of human nature is both a loss of liberty and capacity for forgiveness. As Voegelin comments, you can manage social anxiety by trust (Christianity) or certitude (Gnosticism), and the choice is stark: “There is no alternative to an eschatological extravaganza but to accept the mystery of the cosmos.”

Dignity

Does a fresh name dignity make? Not according to Shree Paradkar :

In that moment I realized I’d gone from being Indian to being South Asian to be a person of colour to now being either Black or Indigenous and a Person of Colour. In the span of a few years, my identity had been diluted beyond recognition. This absolute homogenization is the opposite of what the term BIPOC was meant to do.

The Toronto Star’s race and gender columnist, Paradkar wants a stable vantage point to look out upon the world. Kolnai calls such a vantage privilege and argues it is basic to human dignity. From a heightened position:

I am able to make comparisons, estimate distances, and penetrate spatial structures as I could not otherwise do. I no longer merely represent an automatic focus of vison but embody a privileged and nameable focus of visual perception and thus, in a sense, an enhanced centrality of consciousness. In some respect and some measure, I have also gained a certain distance from the earth and a relative independence from it.

The left’s fevered rewording aims to subvert hierarchy but without vantage points—the nodes of heightened consciousness embodied in establishment—moral data is misrecognized and we lose perspective on human want.

Paradkar makes Orwell’s point: BIPOC is an abstraction, it robs her of a “nameable focus of visual perception.” She realizes that there is no diversity of persons—no autonomy—without privilege: her being Indian—with the distance from others this entails—is a particular legacy of her ancestors. Absent this concreteness, there is only futurism, with all the narrowing and simplification this implies. Paradkar is right to complain; homogenization and dignity are contraries. The left’s fevered rewording aims to subvert hierarchy but without vantage points—the nodes of heightened consciousness embodied in establishment—moral data is misrecognized and we lose perspective on human want. Established order is lost in the flurry of names, but this means that extravagant need gets muddled with urgent need, and so leftists think that the wish for gender reassignment surgery is on a par with the indignities suffered by displaced migrants. A peculiar blindness results. OnlyFans, for example, is celebrated as liberated sex work but in matching sexual need to the gig economy, leftists seem to have lost their traditional mistrust of capital, never mind indifference to the plight of those on the margins.

Paradkar intuits that the most important things cannot be open to revision, that justice requires settled order, or what Hume calls, “external establish’d perswasions.” Advanced humanitarianism has a frenetic quality because it is tied to the philosophy of history in Hegelian Marxism, which posits that nature varies with history. The accent is on change, not being. We have been here before. The Puritan “commands for truth” emerged from the late medieval nominalist controversy whether God could command that a square be a three-sided figure or fire cold. At odds with concrete being, our frenetic nominalism is irked by what Kolnai called the splitness of being and Voegelin the in-between. Wrangling over names and values is part of the normal wear and tear of politics familiar to us all, but this points towards our politics having a patched-up, rather than pellucid, quality. Pope Francis identified rapidification as the hallmark of technoscience futurism and in terms like reproductive health and assisted dying we sense the shift from a reform-minded muddling through to a pristine planned end times.

Not for the left, however, is the Pauline tension between the Old Adam and the New. Refusing to rest in the in-between, sanctifying language expresses the Hegelian Marxist drive to “an egalitarian and all-human, ultra-revolutionary vision of perfection” (Kolnai). Intrusion, not forbearance, is the mark of contemporary nominalism because splitness is an irritant, taking the gloss off the shimmer of its futurism. Hegelian Marxism, Kolnai explains, is “bent on determining the whole of human reality according to the pattern of an unnatural utopia and reducing every aspect and detail of men’s lives to a function of One all-absorbing political Will.”

The in-between being our condition, it follows that every gain of the “ultra-revolutionary” is feeble, demanding yet more progress, more intensity, more intrusion. A management treadmill is necessary, lest gains evaporates. The “commanding heights” (Lenin) of the new order are the managers of campus, corporate, foundation, non-profit, and governmental bureaucracies, deploying an administrative machinery honed by MBA programmes across the land. Armed with metrics, Twitter, and commands for truth, the vanguard manages not by phronesis but geometry (Schmitt), treating complex rooted persons as mere chess pieces on a board (Smith). Anxious for the future, as Kolnai perceptively observed, progressivism “no longer tolerates superiorities, but does tolerate tyranny with surprising ease; its desire is not to maintain its dignity in the face of power or superior authority, but to install powers and authorities in which it can feel itself completely ‘embodied.’” It is this immodesty which makes the left’s march through the establishment so unforgiving.

The Prophetic Spirit

The new nominalism mauls dignity but its Puritanism is not simply perverse. Its emphasis stems from the prophetic, a demand that we excise what distorts cognition, judgment, and value discernment. The prophetic runs the risk of Gnosticism, as Voegelin warned, but conservatism has a penchant for cozying up to long-standing social forms that stunt the human spirit. Liberal conservatives welcome reform that rid us of irrationalities, value-blindness, institutional abuse, and indifferentism. Conceding that progressives are traditionally more attuned to the prophetic spirit, conservatives can nonetheless point to irrationalism, overreach, and delusion on the left. Indeed, rightists think progressives inclined to such flaws because our lot is precarious, reengineering all too liable to misadventure, and a cavalier attitude to history apt to mischaracterize past endeavour.

Influenced by the Enlightenment, liberal conservatism has no desire to return to blasphemy laws, and sees in the contemporary left a new variation on that ancient theme. Since conservatism is a disposition rather than an ideology, an amalgam of sentiments rather than a set of axioms, it has no ready handbook to help those perplexed by the welter of lefty linguistic changes. However, there is a value framework available to conservatives to test when change is warranted. Changes to ancestral names that convey autonomy and dignity must be resisted. In addition, we can require that proposed changes be honest, rational, and peaceable.

The concrete needs leavening, certainly, but conservatives can request intellectual honesty. When we hear student debt framed as “policy violence,” we are right to be skeptical. The change robs of all seriousness arguably the most important category of political theory—violence. Think only of the scrutiny of violence in the works of Plato, Augustine, de Vitoria, Hobbes, and Sorel. Comparably, in swapping shanty towns for spontaneous settlements the depth of reflection on property law as basic to good social order is ignored. It is not only reading Locke that would give pause, but theorists as different as Hume and Bakunin. Similarly, we can suspect a lack of intellectual consistency when a 2020 report of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine gives its gloss on the acronym LGBTQIA+: “The beauty of individuality is that self-expression, as well as personal and romantic choices, can manifest in a multitude of ways.”

We are left to wonder how a libertarianism about sexuality ends up as a platform for collectivist politics. Polemical changes should be treated as engagements with the long history of political and legal thought, and conservatives can be confident of winning some of those honest tussles.

Rationality demands an appreciation of complexity and explains why there are books. We can ask those who would reach into the unconscious that they test the rationality of their efforts by consulting the very many difficult books of the psychoanalytical tradition. We can ask those who prefer to talk of mass incarceration rather than punishment to explain why we are wrong to give weight to Adam Smith’s pages on “animal resentment.” History and nature are measures of rationality, and so, with Jefferson, we can evoke self-evident truth and still reject the false clarity of commands for truth that side-line complexity.

An illustration is a New York Times map from March 1, 2022. Tracking the displaced of the Ukrainian War, the newspaper labeled those fleeing west refugees but those going to Russia migrants. Different names were used, because the press is committed to an amped-up narrative in which Russia is an evil aggressor. Who would go there for succor? The befuddled labelling arose from ignorance of the complexity of Ukraine’s history and varied loyalties of its people. Under criticism, by March 5, the language had flipped, but the most the newspaper could muster were the labels refugees and people to Russia. Overreach always stems from ignoring the value of complexity. Not everything is in books, but they exist to make us mindful of the scope of history and the world. There is a reason why Mary, the Sedes Sapientiae, is often depicted reading a book.

There can be no peace until we are reconciled with the worth and tragedy of our earthly lives as an in-between. Futurism picks out one pole and vitalism another. Sanctifying language—especially the sexual lexicon we are encouraged to embrace—clings to the abstract and devalues the cosmic. Faux intellectualism, irritability, and inclemency are the outcome and conservatives happily offer as an alternative to “the monistic spirit of utopia” (Kolnai), a warmth of sentiment cherishing displays of balance, modesty, and tolerance.