No doubt that it is the duty of judges to say what they believe the law is, but that does not mean they are the only ones - juries have their role to play.

Filling the Gap in Colonial Political Thought

When we think of the origins of the American tradition of political liberty, we think of the American Founding—the extraordinary era of political creativity that began with resistance to Britain and culminated in the ratification of the Constitution and the creation of a new republican nation. But where did those who made the Revolution and created the new nation get the political ideas immortalized in texts like the Declaration of Independence?

In the popular imagination, the Spirit of ’76 was the product of the rare political genius of the Founders. In this heroic account, there’s no need to probe the roots of the Founders’ ideas; their status as quasi-mythical lawgivers is explanation enough. Scholars, however, have sought the roots of the Founders’ ideas in the classical and Christian heritage of European thought, and in particular in the tumultuous political debates of 17th and 18th century England—a time of civil war and revolution, and of intense debates about rights, republicanism, and resistance.

The colonists who made a Revolution against the most powerful empire in the world were indeed political geniuses. It’s also true that their ideas were shaped by the seminal thinkers of the European tradition like John Locke. But what effect did the long political experience of the American colonists in the empire have on the Founders’ thinking and, more broadly, on the development of an American tradition of political liberty?

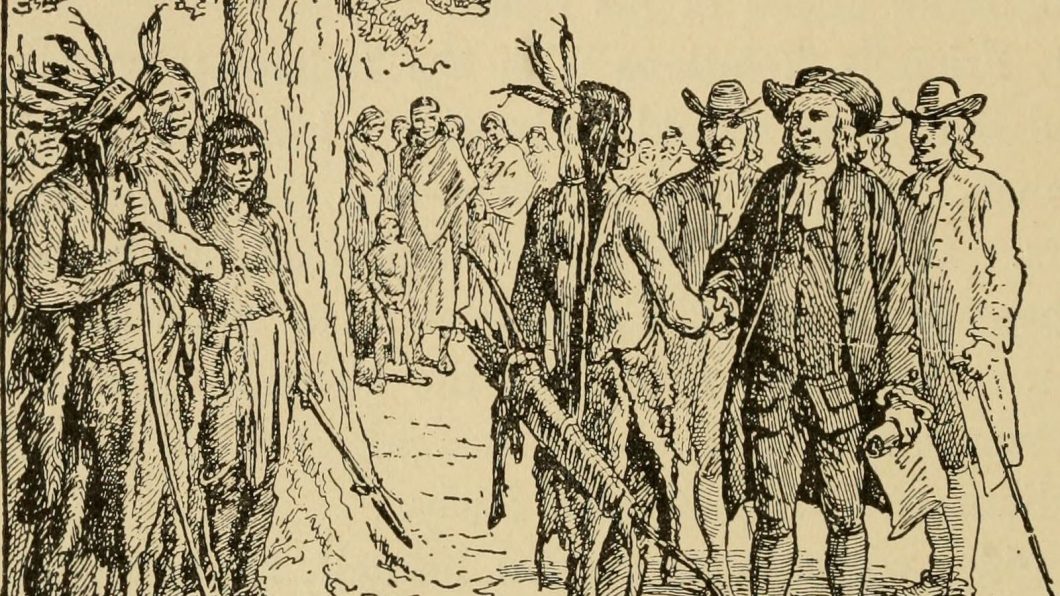

In the second half of the 20th century, scholars became embroiled in a debate about liberalism and republicanism in the American Founding. Yet neither that debate, nor the more recent spate of Founders’ biographies (and musicals!), has paid more than cursory attention to the development of colonial polities and political ideas. Consider that, by the time of the Revolution, the colonies had been largely self-governing polities for over 100 years. They established representative government; asserted their rights and liberties against the Crown and its representatives; developed sophisticated defenses of the constitutions they created for the new polities they constructed; theorized the distribution of authority within the British Empire; and fought against and negotiated with the Native Americans, the Dutch, the French, and the Spanish.

Convinced that these colonial developments deserved more in-depth examination, my coeditor Jack Greene made the case to Liberty Fund in the early 1990s for a collection of colonial political writings to redress this lacuna. When I came to study with Greene a few years later, he involved me in the project, and we began to read a wide range of colonial political writings searching for representative examples that would be suitable for an edited collection. We then had, with the help of several others, the laborious task of finding clean copies of the writings we thought suitable for inclusion, after which we researched and wrote head notes for each selection, setting out the context surrounding its publication.

The result, after many years of work, is Exploring the Bounds of Liberty: Political Writings of Colonial British America from the Glorious Revolution to the American Revolution, out this month from Liberty Fund Press. It reprints in a modern, accessible edition 75 of the most important pamphlets, newspaper essays, and plays published in British America from the late 17th century to the eve of the American Revolution. (A longer e-book edition of another 97 pamphlets is forthcoming from Liberty Fund.) Previously available only in rare book libraries or (latterly) behind the paywall of expensive digital databases, these writings allow not just scholars but members of the public to explore the colonial roots of American political ideas.

Our collection ranges from New England and Nova Scotia in the north to the West Indian islands in the south, and from the Glorious Revolution in America to the final battles over the royal prerogative in the 1760s and 1770s before the British Parliament pushed the mainland colonies into open rebellion. It thus complements two other Liberty Fund publications, Ellis Sandoz’s two-volume Political Sermons of the American Founding Era: 1730-1805 (1991), and American Political Writing During the Founding Era: 1760-1805 (1983), two volumes edited by Charles S. Hyneman and Donald S. Lutz.

What can these long-neglected, often obscure, political writings tell us about the colonists’ ideas of liberty? As shown by William Penn’s The Excellent Priviledge of Liberty and Property (1687), the first pamphlet in our collection, the colonists cherished their rights as English subjects to life, liberty, and property. For Penn the two most important of these rights were to political representation and to jury trials, both of which, he argued, protected English subjects against arbitrary royal power. Representation in a Parliament or a colonial assembly allowed the people to consent to laws that bound them, while juries prevented the Crown from depriving subjects of life and liberty without the consent of their peers.

When the Stuart Kings in the 1680s revoked the charters of the northern colonies, the colonists asserted that their English rights were endangered—rights, they insisted, that all the King’s subjects were entitled to wherever they resided in the empire. To this assertion of the equality of rights and liberty with subjects back in Britain they added another: that it was particularly egregious of the Crown to treat its colonial subjects arbitrarily given that they had risked their lives in a perilous voyage across the ocean and established flourishing colonies in a hostile wilderness.

Both claims were central to Jeremiah Dummer’s sophisticated defense of the New England charters in 1721 (selection number 20), and to Daniel Dulany’s forceful 1728 case for the right of colonists in Maryland to the benefit English laws (selection number 26). In making his case, Dulany imagined America as a Lockean state of nature and contended that the colonists in Maryland had chosen to adopt English law as the best way to guarantee their natural rights. This was a claim echoed by the Virginian Richard Bland (selection number 63), among others, in the imperial crisis of the 1760s and 1770s.

The writings in our collection also show the colonists exploring the implications of their commitment to English liberty by asserting the power of their local assemblies against the prerogative of governors, challenging the powers of the unelected colonial councils and the legitimacy of prerogative equity courts, and by thinking deeply about the nature of constitutionalism, as the anonymous authors of a series of essays in the Maryland Gazette did in 1748 (selection number 42). Our collection does not, however, ignore those who pushed back against the more radical democratizing tendencies of colonial thought, like Gershom Bulkeley of Connecticut (selection number 3), who argued against resisting the Stuarts in the 1680s, and Archibald Kennedy of New York (selection number 43), who warned that the increasing power of the colonial assemblies in the 1750s weakened the colonies in the face of the French and Indian threat.

Nor is Exploring the Bounds of Liberty limited to writings about political liberty. It also includes writings about political economy that show the colonists grappling with duties levied by the Crown on their exports as well as with parliamentary laws which limited with whom they could trade and on what terms. Other writings deal with the vexed question of whether colonial governments could issue paper money, an ongoing source of tension with London in the 18th century. The tension between the growth of African American slavery and the English colonists’ commitment to liberty also features in several of the writings in our collection, as does the legal status of Native Americans who were occupying the land which many of the colonists insisted was in fact a wilderness before they arrived, a theme that I explore in my own interpretation of colonial political thought.[1]

Ultimately, though, our intent is not to dictate to our readers what is and is not important in colonial political thought. It is rather to invite them to explore for themselves this rich body of writings about liberty. While the time may never come when names like Jeremiah Dummer trip off the tongue as easily as those of Thomas Jefferson or James Madison, we hope that Exploring the Bounds of Liberty will lead scholars to take colonial political ideas seriously while educating the general public about the deepest roots of America’s long tradition of political liberty.

[1] Craig Yirush, Settlers, Liberty, and Empire: The Roots of Early American Political Theory (Cambridge University Press, 2011).