A Glorious Future Ahead

The best comment on the problem Helen Dale’s acute essay identifies comes from a slightly unexpected source: the comedian Reginald D. Hunter, who hails from Albany, Georgia, but has been living in the UK for a quarter of a century. Only an African American could get away with this joke at a London stand-up comedy show: “When I hear what the Welsh say about the English, and what the Scots say about the English, and what the Northern Irish say about each other and everyone else, and how the English just don’t care, I reckon you guys don’t need Black people at all.”

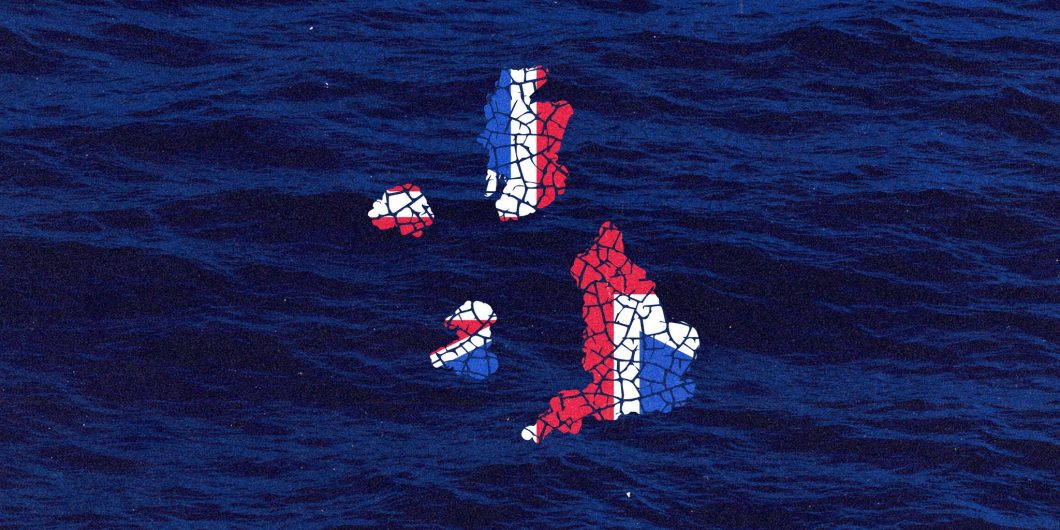

Americans are often surprised by how much the inhabitants of these small offshore islands differ among themselves, despite the obvious fact that such diversity is both a cause and a consequence of having peopled much of the world. In fact, the United Kingdom is no less artificial and delicately balanced a creation as the United States—just smaller.

Helen Dale is an Australian living in the United Kingdom and she devotes the bulk of her essay to the question of Scottish independence. This is a matter of all-consuming importance to Scots; south of the border, not so much. This is not because the English dislike the Scots—as Ms. Dale says, most of us love the country and admire its people—but because we tend to assume that what happens there does not affect us much. There is also the unspoken assumption that was articulated long ago by Dr. Samuel Johnson—that the Scots who want to change the world sooner or later emigrate. “Norway, too, has noble wild prospects; and Lapland is remarkable for prodigious noble wild prospects. But, Sir, let me tell you, the noblest prospect which a Scotchman ever sees, is the high road that leads him to England!”

Scottish National Party

The 2014 referendum decided nothing, because the Scottish National Party (SNP) will never renounce its goal of full sovereignty. Neither the devolution they have nor the fully federal solution discussed by Ms. Dale will ever satisfy the tartan zealots. Given the chance, they will keep rerunning plebiscites until they win one.

An independent Scotland would in reality have less control over its destiny than it does as part of the UK, mainly for reasons of economics, Europe, and security. It could not rely on the English taxpayer to finance the left-wing policies pursued by the SNP-Green administration in Holyrood. At present, the UK Treasury gives the Scottish Government some £41 billion ($50 billion) annually. This subsidy means that the five million Scots enjoy £129 per capita of public money spent on them, compared to £100 per capita for the 55 million English. Even without the subsidies, as Helen Dale points out, Sterlingisation would require draconian cuts in public expenditure. So would adopting the euro—which raises the thorny question of a future Scottish republic’s relationship with Europe.

If they ever get lucky enough to win a referendum, the first thing the SNP promise to do after independence is to apply to rejoin the European Union—in other words, to renounce a large part of the sovereignty they would only just have acquired. Even if the EU were to accept Scotland as a candidate member (which would mean overcoming the veto of several member states, particularly Spain, that detest separatists), actual membership may take decades to negotiate. As things stand, Scotland would have a budget deficit of 22.4 per cent—higher even than that of Greece a decade ago, when it came close to being kicked out of the euro club. Brussels would never tolerate such fiscal incontinence. Even if Scotland could sort out its financial affairs, membership in the EU would create a hard border with England. At present, Anglo-Scottish trade is worth three times as much as Scotland’s trade with the EU. Having seen how damaging the Northern Ireland Protocol has been to their neighbours across the Irish Sea, the last thing most Scots want is to create new trade barriers with the rest of the UK.

Then there is national security—suddenly much higher on the list of voters’ priorities thanks to Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. The long-standing SNP policy of unilateral nuclear disarmament would mean closing the British nuclear bases on the Clyde. There are no other practical options for basing Trident submarines outside Scotland. Hobbling Europe’s most powerful nuclear deterrent would hamper Western defences against Russian aggression, just when Sweden and Finland are joining NATO precisely in order to benefit from its nuclear umbrella. First Minister Nicola Sturgeon is committed to signing the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which no other NATO member state has done, and her Green coalition partners are resolutely opposed to membership of the alliance. It is hard to imagine swing voters in Scotland deliberately rolling the dice on national security while full-scale war on the European Continent continues.

Even at the cultural level, for Scots to vote to break up a key NATO member state at such a time would fly in the face of nearly three centuries of British history. Ireland had uprisings in both the Napoleonic and the Great Wars. Having left the UK after partition and civil war, the Irish Republic remained neutral in the Second World War—though thousands of Irishmen fought in the British Army. But Scotland last had an insurrection in 1745. Ever since, Scots have been conspicuous for their patriotic fervour and martial prowess. Having fought against various authoritarian and totalitarian regimes in both world wars as part of the UK, they are unlikely to sully a glorious history by sabotaging the Ukrainians’ struggle to preserve their independence against dictatorship. Handing such a victory to Russian imperialism would be a curious way to show the world that Scotland had renounced all connection to the British variety.

For all these reasons, I should be surprised if Scotland gets as far as an “Indyref2,” as Ms. Sturgeon calls her proposed independence referendum. But she is not easily deterred. Notwithstanding the legal and constitutional reality that no such plebiscite can be held without the permission of the Westminster Parliament, the First Minister is floating the idea of a consultative vote, perhaps asking a differently worded question, in the hope of creating an unstoppable political momentum. This blatant attempt to circumvent the law will doubtless end up in the courts, but the inevitable delays entailed by litigation won’t trouble “Miss Nippy” (as she is popularly known). Keeping the independence question in the air is a useful distraction from the lamentable record of the SNP on health, education, energy, and other pocketbook issues. A permanent question mark over Scotland’s status has enabled the nationalists to run it as virtually a one-party state.

The British have a future ahead more glorious even than their past. If this is the twilight of the United Kingdom, it is the twilight of morning, not evening.

The Northern Ireland Protocol

I agree with almost everything Helen Dale says about Northern Ireland, but I am slightly more sympathetic than she is towards the Protestant community there—despite being a cradle Catholic. Unionists are paranoid about betrayal by British governments; but paranoia is not necessarily irrational if you really have been repeatedly sold out. The Northern Ireland Protocol is only the latest chapter in a history of broken government promises, sometimes made in bad faith, which have conditioned “loyalists” to expect disloyalty. No wonder unionists fall back on their old slogan: “No surrender!”

In the specific case of the Protocol, the bad faith mostly comes from the European side. To claim, as they do, that creating an artificial hard border inside the UK is necessary not only for the sake of the EU Single Market, but also to preserve peace in Northern Ireland, is not only bogus but dangerous to boot. The Belfast Good Friday Agreement, which Ms. Dale wittily dubs a “foreign policy koala, which everyone claims to protect,” is actually protected by neither of the great powers that purports to do so: the United States and the European Union. For both, the Protocol is a fig leaf for the pursuit of Irish irredentism. Anyone can see the damage it has already done, both by its theory and its practice, to the fragile peace achieved by a quarter-century of normalisation since the Agreement.

If the EU really cared about preserving peace in the Province, it would be ready at least to discuss the measures that the British Government has proposed to mitigate that damage. These are designed to facilitate the flow of goods from the mainland to Northern Ireland by limiting the onerous checks and red tape to items that are ultimately destined for the Irish Republic. The EU’s protectionist reflexes have combined with the ulterior motive of detaching the Province from the rest of the UK to turn its ports into choke-points.

What a difference the absence of a land border still makes! It is hard to imagine the US or even the EU encouraging the destabilising project of Irish unification if the North were not separated from mainland Britain by a narrow channel of the Irish Sea. Would Americans tolerate an attempt by Russia or China or Russia to detach Alaska from the Union?

The truth is that the Protocol was never even necessary. On this, I must beg to differ from Ms. Dale, who states that the EU was “rightly concerned that importers would use it as a backdoor into the customs union.” The avoidance of a hard border between the Republic of Ireland and the North was always a technical, second-order issue that the EU deliberately magnified into a first-order one to pressure the British. The EU has other porous borders (for example, Poland’s with Ukraine) which pose no threat to the “integrity” of the Single Market. In the unlikely event that large-scale evasion of customs controls had arisen, it could have been dealt with by simple measures while preserving the “soft” character of an intra-Irish frontier that had survived a 30-year cross-border terrorist campaign.

In any case, the soft border was not the purpose of the Good Friday Agreement but a means to an end, namely peace in Northern Ireland. The two governments had managed to keep the peace for two decades until the EU, aided and abetted by the US, decided to intervene. It is not Brexit but their meddling that has rendered the Stormont assembly dysfunctional and raised the spectre of a return to “the Troubles.”

The keystone of the Good Friday Agreement is the principle of consent: no constitutional change in the status of Northern Ireland without the consent of both communities. But the unionists have never given their consent to the Protocol, which has been imposed by the European Union and its operation enforced by the European Court of Justice. To preserve this unsustainable status quo, Brussels is prepared in effect to impose sanctions on the UK by suspending its trade agreement. Throughout the Brexit negotiations, it felt to many as though Brussels was trying to penalise Britain for leaving the EU by imposing terms that left Northern Ireland semi-detached, at least in economic terms. Now the EU seems to be raising the price, just as global stagflation looms. If Ms. Dale is correct, and “a lot of English people would flick Northern Ireland off like a scab,” then now might be the optimum moment for the EU to bully or tempt the British into flicking the scab.

That ugly simile is not quite Helen Dale’s last word on the subject. She ends with a more lyrical, but ambiguous metaphor: “The kingdom is divided, now, and its future is shrouded in mist.” Yet mist invariably clears as it is dispelled by the rays of the sun. The British have a future ahead more glorious even than their past. If this is the twilight of the United Kingdom, it is the twilight of morning, not evening.