Demons at Work

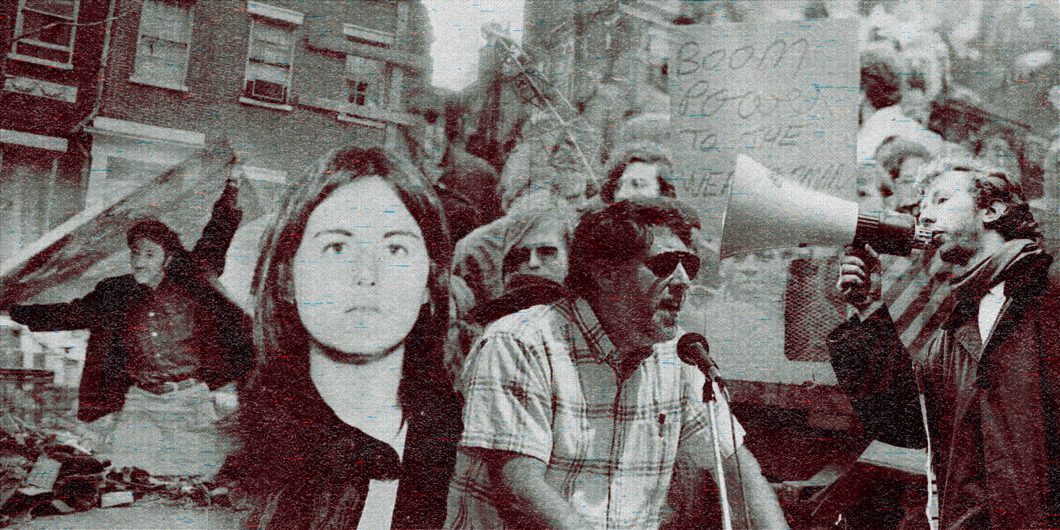

The Weather Underground’s revolutionary effort to slaughter young non-commissioned officers and their dates at a military dance failed. The explosives that were to be placed in bombs went off prematurely, before the nails meant to rip and maim those young bodies were packed into them. The terrorists had succeeded in killing three of their own and sending two into hiding (supported by a network of sympathizers and admirers). They failed in their plan to blow up the Columbia University administration building and only partially succeeded with their bombs at the Pentagon. They did succeed in armed robbery, however, taking $1.6 million in loot from a Brink’s truck and murdering three working-class guards and police officers. They advocated and dementedly attempted to spark the violent overthrow of the United States government.

If they had worn white hoods or the insignia of right-wing militia, they would still be in prison. They were left-wing butchers and would-be butchers, however, so the fates have been kinder to them. Susan Rosenberg, part of the Brink’s heist with its consequent murder of innocents, was pardoned by Bill Clinton and wrote her memoirs; Kathy Boudin was paroled, got a Doctor of Education Degree from Columbia University Teachers College, became an adjunct professor of Social Work at Columbia University and co-founder and co-director of the Columbia University Center for Justice; Cathy Wilkerson taught high school and published her self-promoting memoir; Bill Ayers became a professor of education at the University of Illinois, Chicago and helped launch Barack Obama’s Illinois political career; Bernardine Dohrn, who found the knife in Sharon Tate’s stomach “groovy,” went on to teach at Northwestern University’s School of Law.

Jay Nordlinger has written two essays here. The first is a moral narrative of the Weather Underground itself: its actors, crimes, and mostly impenitent major figures; its attraction to violence; its hypocrisies. He says nothing new. The second essay, on legacy, by focusing on Antifa, Trump supporters’ verbal threats over the 2020 election results, and “a right-wing insurrectionist mob [that] attacked the U.S. Capitol, leaving carnage in its wake,” seeks to draw for us the rather unoriginal conclusions that “extremism” and “violence” go hand in hand and that civilization is fragile.

Jay Nordlinger is struck, above all, by three aspects of the Weather Underground: their attraction to violence; their lack of repentance; their widespread acceptance as good folk who made some mistakes. His Weathermen “were in love with violence.” Why? Nordlinger offers a string of reasons: they were impatient; they supported and learned from “their fellow communists” in Vietnam, Cuba, and China; they admired their peer terrorists in Europe. “As much as anything,” however, “they loved violence and sex.” They drooled over the Manson family. Maybe, but there is no effort here to locate these generally privileged, wealthy, and murderous white kids in the American society in which they were raised and educated, to link their reading, writing, and actions with the traditions of revolutionary violence of which they were heirs, or to see them in dialogue or contestation with the Old Left. Instead, we have the shopworn narrative of their well-known public acts. Nordlinger rightly sees that their lack of repentance is easily explained: In their minds still, they were and are right about America; they were and are right in their goals; they were wrong only in their most extreme acts.

The Weather Underground were and still are sustained in this sense of themselves by academic and intellectual circles that generally succeeded in portraying them as impatient “activists” fighting for peace and a better world. Nordlinger mentions (without detail) sympathetic portraits of such militants offered by 60 Minutes, the New York Times, and other major media outlets, but he concludes merely that “some people” invest them “with romance.” The rehabilitation in law, public memory, political life, and individual academic influence of the members of the Weather Underground, however, is a major part of their legacy. We needed less narrative and more consideration of these phenomena. Historical judgment is of the profoundest intellectual, moral, and cultural importance. Why are they “invested… with romance” by any significant segment of observers?

Rich kids wishing to remake the world anew “by any means necessary” have little understanding of the pathologies, narcissism, brutality, and indifference to ordinary lives of those who would make use of their bodies.

Nordlinger likes David French’s recent explanation of why “Right” and “Left” reach different conclusions about political criminality. People, in this view, are limited in their knowledge, familiar with and remembering violence against their own side, but tending “not to know” about violence against the other camp. I’m far from convinced of that. Stephen Spender, in his essay in The God That Failed, came closer to the truth. Seeing the victims of their enemies, people see real flesh and blood, beings whose lives were cut short, individuals with personalities and hopes. Seeing the victims produced of their own side, people see abstractions, numbers, data, and “collateral damage.” That human failing is a mighty and dreadful political force.

There is a compelling apprehension available not only of the Weather Underground, but also of the Red Army Faction, the Baader-Meinhof gang, the Japanese Red Army, the Symbionese Liberation Army, the Brigati Rossi, et al. It was written 150 years ago. In Demons, Dostoevsky offered a searing and prescient portrait of the nihilism that has accompanied and ultimately controlled the revolutionary forces of the modern age. Stavrogin, puppeteer of the would-be social justice activists, and manipulator of scenarios, leads the idealists into destruction for the sake and thrill of destruction.

Rich kids wishing to remake the world anew “by any means necessary” have little understanding of the pathologies, narcissism, brutality, and indifference to ordinary lives of those who would make use of their bodies. The revolutionary Left of the 20th century (and beyond), led and stage-managed by its tyrants, has been the most destructive and murderous agent in human history; it has surpassed all other systems for producing widows, widowers, and orphans. It remains admired. Given the enormity of its crimes, there is little moral let alone criminal accountability. The Weather Underground lacked the power to kill as many as it wished to kill, but we should be haunted by its crimes, its love of terror, its narcissism, its nihilism, and its absolutions by our cultural elites.

Given Nordlinger’s view that the Left and Right don’t truly “know” that there are victims on the other side, his essay has a certain symmetry. He will let the Left know what it apparently did not know and recite the crimes and inadequate remorse of the Weather Underground. He must also now inform or remind the uninformed Right of its own Trumpian threats of violence against Georgia Republican officials and finally the “carnage” of January 6. In short, his essay on the rage and consequences of the Weather Underground concludes with the struggle of the National Review against the Claremont Review of Books.