Islam and the West: Mustafa Akyol Responds

I felt privileged to read three thoughtful responses by three wise scholars to my Liberty Forum essay on “Islam, Blasphemy, and the East-West Divide.”

Hillel Fradkin raises very apt questions on whether contemporary Muslims are really willing to adopt modern ways and norms. On this, I had insinuated a task for Western leaders, that they should ensure “Muslims feel at home in the modern world rather than being ‘otherized’ by that world.” Fradkin reminds us of the other side of the coin: That “it is Muslims who largely insist on their ‘otherness.’” Do I agree?

As someone who has been engaging both sides of this great civilizational divide for quite a while, I would say I partly agree. On that other side of the coin, there really is a view among some Muslims that the world outside of the umma (global Muslim community) is that of jahiliya, or “ignorance,” and its ways are by definition “falsehood.” But this is the view of the Islamists, whose grip on the broader Muslim community is not absolute—it is in fact fraying, at least in the West, as a recent story in The Economist also pointed out.

When you flip the coin back, there are really deep-rooted biases in the West against any religion (or race) that looks different. These roots are in the very forces that excluded Jews from Europe despite the Haskalah, or the Jewish Enlightenment, of the 18th century, and the subsequent Jewish effort to assimilate, in order to became “Germans of the Mosaic faith.” While advocating a Muslim Enlightenment, which might take root in the West more than anywhere else, I do have this as a background concern, one that might derail a promising process.

Nader Hashemi seems to get the Western promise for Islam well, as he notes: “An ethical and humanistic reinterpretation of Islam can only take place in a free and democratic society.” That is why Fazlur Rahman could not continue teaching in Pakistan and came to America. (That is probably why, in fact, both Hashemi and myself, as Muslims who argue for “an ethical and humanistic reinterpretation of Islam,” are now in America rather than somewhere else.)

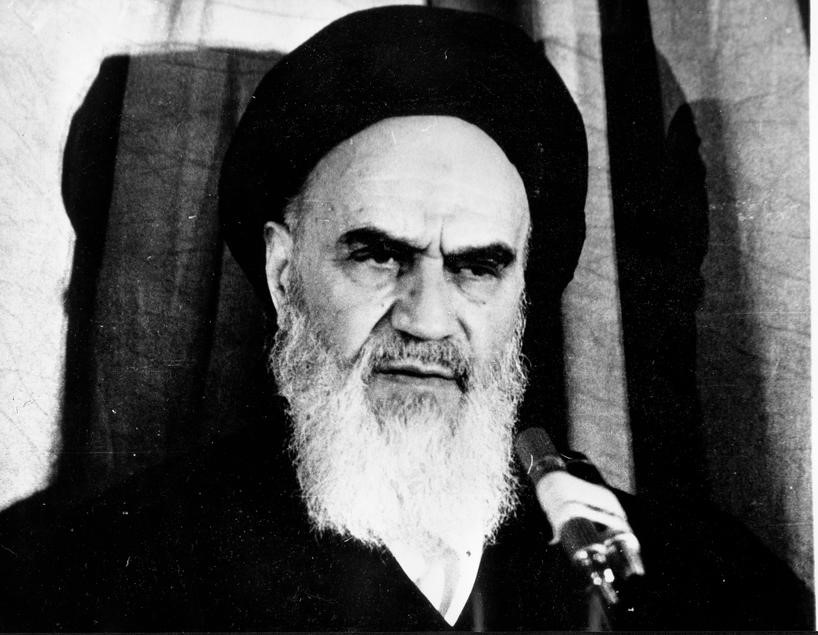

But Hashemi is also right to criticize the West for sometimes failing to live up to its own ideals. The contrast he draws between the Western response to the death threat on Salman Rushdie by the Iranian Ayatollah and the actual murder of Jamal Khashoggi by order of the Saudi Crown Prince is right on point. Such Western double standards exist on a variety of issues, giving the Islamists ample material for their version of whataboutism. So, if the West somehow wishes to help the quandary of Islam, the best thing it can do is stick to its own liberal principles.

Which brings me to the third essay, the one by Luma Simms, which is probably the most provocative of all three. Her point is that an Enlightenment has not yet come to pass in the Muslim world, so “fideism” runs deep, and hence societies are deeply illiberal. “The fundamental problem in the Middle Eastern world,” she frankly writes, “is not necessarily the form of government, but the intellectual and moral state of the majority of the people.” (Emphasis in original.)

I am no believer in political correctness, and see what is meant here, and also see that it has some merit. “The problem” that we’re addressing here—the rejection of free speech—is not only a political matter, but religious and social one. For example, those who are eager to execute all blasphemers in Pakistan, real or perceived, are not just government officials but large segments of “the people.”

However, I still can’t accept the lesson Simms seems to be deriving from this problem with “the people”: A preference for “progressive” autocracies.

Simms’s examples are the “progressive, Westernized, Zoroastrian-friendly kingdom” of the shah, and the staunchly secular republic of Kemal Ataturk. I am no stranger to the latter one, and I must confess that I have been proven wrong with my initial hopes and dreams about the “soft Islamists” who had promised to take over from the secularists in the early 2000’s supposedly to turn Turkey into a liberal democracy. Instead, not too unreminiscent of the more explicit revolution in Iran, their subtle revolution ultimately tilted toward autocracy—one that is getting worse by the day.

Even so, I don’t think that Ataturk’s Turkey or the shah’s Iran were the ideal “progressive” regimes that we should hope to see in the region. The same goes for the brutal government of Egyptian President Sisi, which is finding some undeserved leniency in Western capitals. For none of these regimes have really given their societies what should be the bedrock of modern civilization: individual freedom. They have suppressed dissent, replaced religious dogmatism with nationalist fervor, and enacted cults of personalities. Moreover, with their illiberal notions of modernity—exemplified in the female headscarf being banned in the shah’s Iran and Ataturk’s Turkey—they paved the way for their demise. Conservative Islam, at the end, returned with a vengeance.

If there is any good model in the region, it is what Hashemi points out: The post-Arab Spring Tunisia, where Islamists and secularists, with mutual compromise, made a liberal constitution together.

Meanwhile, matters of Islamic jurisprudence, in addition to the meaning of “honor” and “dignity” as Fradkin rightly points out, must be thoroughly discussed in Muslim societies. Because the challenge, let me repeat, is not just political but also religious and cultural. But wasn’t it exactly like that in Christendom a while ago, when Locke wrote A Letter Concerning Toleration, and toleration was a radical idea?