With its focus on reconciliation and toleration, Black Panther offers a surprising defense of classical liberalism.

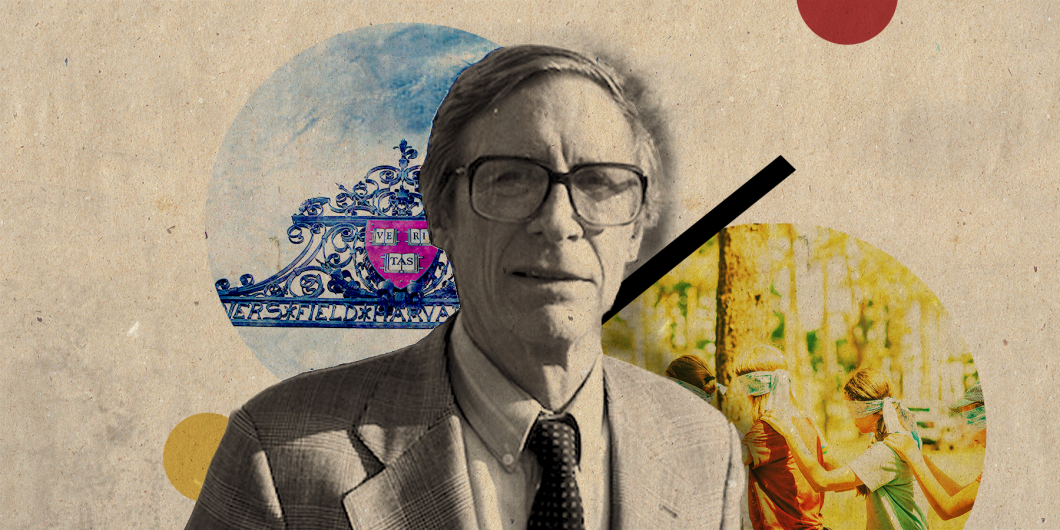

On the Legacy of A Theory of Justice

A Theory of Justice (1971)was one of the most influential works of twentieth-century political theory, and we have now arrived at its 50th anniversary. How should we think about its legacy?

Most Law & Liberty readers are familiar with Theory’s basic arguments. But the task of assessing its legacy is complicated by the fact that Rawls’s ideas changed over time, and the reasons for these changes remain a matter of lively controversy. I am not a Rawlsian, and my interest in the finer points of Rawlsian scholarship has limits. But as someone who routinely teaches Rawls and sympathizes with elements of his project, I do have some thoughts about its legacy.

Rawls’s lifelong project was an attempt at political conflict-resolution at a high level of philosophical abstraction. He worked for the most part in what he called “ideal theory,” discussing political arrangements as they might be “but for” history and happenstance. Yet Rawls always regarded ideal theory as a prelude to “non-ideal theory,” the task of reforming political arrangements in order to bring them more in line with reason. He was something of a “rationalist,” as Michael Oakeshott employed the term. But unlike an extreme rationalist, he did not theorize from a blank slate. Rather, he began from certain moral and political sentiments that are present in contemporary liberal society.

Rawls’s Project in Theory

The fundamental ideas that frame Theory derive from these commonly held sentiments: democracy, fairness, equal liberty, equal opportunity, and the need for social cooperation. Rawls presents these as axiomatic even though, for others, they might warrant investigation. Against this background, Theory tries to describe the principles of liberal freedom and equality in such a way that everyone, or nearly everyone, will accept the end results as fair, no matter their personal circumstances. Rich or poor, fortunate or unfortunate, all citizens will sense they are involved in a cooperative system that acknowledges and respects them as persons.

Theory has three parts. The first offers two principles of justice and explains, using the thought experiment of the “original position” and its “veil of ignorance,” why citizens should accept these principles for governing what Rawls calls the “basic structure” of society. The second part considers how these principles might be institutionalized in political practices and norms. The third part endeavors to show how participation in the resulting “well-ordered society” is compatible with a robust, overall conception of the good, which Rawls hopes citizens will find attractive. If Rawls were successful, citizens would enjoy the pursuit of a good life as free and rational beings in a stable, well-ordered society.

Rawls’s two principles of justice purport to balance liberty and equality. But in fact they demand radical egalitarianism. True, everyone is to enjoy an extensive list of “basic liberties”—such is the gist of the first principle, which Rawls presents as “lexically prior” to the second. But the second nevertheless opens the door to massive state intervention in order to guarantee not only formal but substantive equality of opportunity, as well as a far-reaching system of redistribution in order to supply welfare and to regulate economic inequalities over time. Not all of this is immediately evident in the way Rawls stated the second principle: “Social and economic inequalities are to be arranged so that they are both: (a) to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged . . . and (b) attached to offices and positions open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity.”

In fact, it is hard to overstate the ambition of Rawls’s project in Theory; and it took at least two decades for the critical dust to settle. Early on, the praise was epic. For instance, Robert Nozick, who was quite critical of Theory, nevertheless described it in 1974 as “a powerful, deep, subtle, wide-ranging, systematic work in political and moral philosophy which has not seen its like since the writings of John Stuart Mill, if then.”

But over time a number of exacting criticisms emerged. H.L.A. Hart revealed how Rawls’s first principle paid insufficient attention to competing rights and liberties and to the tension between liberty and other important social goods. Nozick himself showed that the concept of distributive justice in Rawls’s second principle was at odds with a “historical-entitlement” view grounded in individual rights and freedoms. The original position and veil of ignorance were derided by Allan Bloom as a “bloodless abstraction” offering no motive for anyone to continue under Rawls’s system if he didn’t like the outcomes. Michael Sandel argued that Rawls’s abstract theorizing paid insufficient regard to the concrete, communal wellsprings of justice. Marxists attacked him for being an ideologist of the status quo, and feminists for his apparent acceptance of the hierarchical family. Rawls’s Theory was undoubtedly successful in reshaping the conversation in political philosophy, but it certainly didn’t satisfy everyone.

Revision: Political Liberalism

Nor was Rawls himself satisfied. Accounts differ as to the precise reason for Rawls’s recasting of Theory in a second book called Political Liberalism (1993), but most agree that it stemmed from the incompatibility of his theory with reasonable pluralism concerning moral concepts such as justice and the good. Rawls came to doubt that his two principles of justice would be endorsed, or, if they were endorsed, that they would remain stable in a pluralist society.

One way to view this (but perhaps it is too simple) is to say Rawls realized that his presentation in Theory “begged the question,” since it assumed without argument one moral framework (neo-Kantianism) among other reasonable rivals. A different way to view it is that Rawls never regarded his theory as hinging on a single moral framework—Kantian or otherwise—but came to realize that given freedom of thought and enough time, rival principles of justice might become attractive. Either way, Rawls had underestimated the problem of reasonable pluralism and now needed to try again.

Rawls’s wrestling with pluralism led him to introduce into Political Liberalism a number of new concepts such as “comprehensive doctrines,” “reasonable pluralism,” the “burdens of judgment,” “overlapping consensus,” “public reason,” and, above all, “legitimacy,” which would become a key part of his attempt to revise his project. Moreover, Rawls now recast his whole theory in a much more abstemious way, presenting it emphatically as a “political conception,” without reliance for its substance or justification on any metaphysical or religious doctrines not already shared among citizens. All these revisions, commonly referred to as Rawls’s “political turn,” enabled Rawls to respond to the problem of pluralism. But they also (I would argue) rendered his theory less coherent, especially in its radical egalitarianism.

In outline, the theory of Political Liberalism goes something like this. In modern liberal societies, citizens clearly embrace multiple, sometimes incompatible “comprehensive doctrines” about life’s meaning and the possibilities of politics. Pluralism need not result from recalcitrance or intellectual laziness, but may arise naturally from legitimate obstacles to discovering truth (what Rawls calls the “burdens of judgment”): conflicting or vague evidence, different life experiences, and competing normative considerations.

But if pluralism is legitimate (if people can and do reasonably hold incompatible comprehensive doctrines) and if we are serious about the value of individual freedom and formal equality, then we should refrain from building political life upon any comprehensive doctrine. To do otherwise would not only violate people’s freedom and equality, it would likely perpetuate ongoing political divisions and conflict.

Instead, Rawls thinks we should discover terms of political agreement that are “freestanding,” referring for their justification not to controversial comprehensive doctrines but to ideas already embedded in our common life together. Moreover, we should limit the scope of political agreement to the most fundamental domain (namely, the “basic structure”)—in the hope that all or most citizens will be able to agree wholeheartedly (i.e., reach an “overlapping consensus”) on the fundamental principles of political cooperation.

Finally, once citizens agree to the principles of the basic structure, they will have touchstones from which to reason about constitutional conflicts that arise. Referring back to the fundamental principles, citizens can offer “public reasons” about what society should do.

At this point, it is fair to ask how well Rawls’s “political turn” (a) responded to the problem of reasonable pluralism while (b) retaining the core elements of his original theory. The results, I think, are mixed. Rawls was right to acknowledge pluralism as a permanent feature of liberal society. His treatment of this topic was not as penetrating as the best theorists of pluralism from Michael Oakeshott and Isaiah Berlin to Stuart Hampshire and Bernard Williams. But it was certainly solid enough to place theoretical obstacles in the way of what we might call the “politics of unified vision.” Rawls affirmed that the U.S. is not and never will be a polity like Calvin’s Geneva where everyone agrees on the ends to be pursued; and it is high time we stopped approaching politics this way.

But when it came to retaining his original theory, Rawls ran into problems. The more he came to appreciate the depth of reasonable pluralism, the more he realized that his second principle of justice in particular (the one relating to equality and inequality) was unlikely to become part of any “overlapping consensus.” Rawls’s egalitarianism may have been attractive within certain moral and political frameworks, but it was certainly not universally attractive and would probably not even command a bare majority of adherents.

The tacit understanding held by most American political actors today is that politics is war. The goal is to win and wield the power of the state in pursuit of one’s own moral vision—enemies be damned. This, however, will not work in a pluralist society committed to freedom and formal equality.

As a consequence, Rawls began to soft-pedal his second principle of justice, beginning with Political Liberalism and ending with his final work, Justice as Fairness: A Restatement (2001), where he writes quite frankly: “[T]he reasoning for the first principle is, I think, quite conclusive; . . . the reasoning for the difference principle, is less conclusive. It turns on a more delicate balance of less decisive considerations.”

The Problem of Liberal Political Legitimacy

Perhaps because his principles of justice seemed less convincing after taking pluralism more seriously, Rawls turned to the topic of legitimacy. This is contested: There are different accounts of why Rawls focused on legitimacy starting in Political Liberalism and continuing through Justice as Fairness. But if his goal were to discover grounds for political unity separate from his two principles of justice, I do not believe he succeeded. This is not only because, as Rawls says repeatedly, his “principle of legitimacy [has] the same basis as the substantive principles of justice.” They flow from the same neo-Kantian spring, I would say. It is also because Rawls’s account of legitimacy is inadequate on its face.

Rawls thinks the exercise of political power among citizens regarded as free and equal is legitimate “only when it is exercised in accordance with a constitution the essentials of which all citizens as free and equal may reasonably be expected to endorse in the light of principles and ideals acceptable to their common human reason.” Rejecting both a “consent theory” of legitimacy and a “tacit-consent theory,” Rawls follows Kant in offering what some call a “hypothetical-consent theory.” Legitimate rules are what citizens might “reasonably be expected” to consent to, not what they actually consent to.

But a problem emerges when political legitimacy is approached this way: What happens when no such agreement about basic principles of justice, let alone the “constitutional essentials,” is forthcoming? Rawls is aware of this. He writes, “there is plainly no guarantee that justice as fairness, or any reasonable conception for a democratic regime, can gain the support of an overlapping consensus and in that way underwrite the stability of its political constitution.” But if no agreement is forthcoming—and this is unfortunately our present state of affairs in the United States and in most liberal regimes—then the problem of legitimacy remains unsolved. The state employs coercive power, because it must do so if the regime is to be maintained. But such coercion will always seem illegitimate to “free and equal” citizens who disagree with its ends.

Rawls’s reply is, in effect, “well, citizens do not have to actually consent; it suffices that they reasonably ought to.” But this to take a notably paternalistic position on the problem of legitimacy, one that is incompatible with ordinary notions of freedom and equality. Who is to decide what “reasonably ought” to be acceptable?

The Failure of Rawls’s Project

In my view, not only Rawls’s account of legitimacy, but also his two principles of justice (both of them) ultimately fail.

The problem with the first principle (equal basic rights and liberties) is that the rights and liberties in question are determined not by any historical account of American constitutionalism and political practices, but by a thought experiment motivated by a distinctly “positive” sense of liberty: “We consider what liberties provide the political and social conditions essential for the adequate development and full exercise of the two moral powers of free and equal persons”—the two powers being the capacity for a sense of justice and a conception of the good.

Notably absent from Rawls’s list of basic liberties is a right to private property in productive assets. This is not an omission, but rather fits Rawls’s desire “to put all citizens in a position to manage their own affairs on a footing of a suitable degree of social and economic equality.” To do this, Rawls must ensure “widespread ownership of productive forces,” by seizing and redistributing productive assets according to a rational plan. It should come as no surprise that Rawls cannot determine in the end whether a “property-owning constitutional democracy” or a “liberal socialist regime” best fits his theory of justice: He says they both do.

Equally problematic is that part of Rawls’s second principle referred to as the “equal opportunity principle”—i.e., insofar as there are “social and economic inequalities,” the “offices and positions” to which they are attached must be “open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity.” The difficulty is that this cannot possibly be achieved. For by “fair equality of opportunity,” Rawls means (see JF II.13) that “those who have the same level of talent and ability and the same willingness to use these gifts should have the same prospects of success regardless of their social class of origin. [All should have] the same prospects of culture and achievement.”

To accomplish this, Rawls proposes that “a free-market system . . . be set within a framework of political and legal institutions” that “establish, among other things, equal opportunities of education for all regardless of family income” and which “adjust the long-run trend of economic forces so as to prevent excessive concentrations of property and wealth, especially those likely to lead to political domination.”

Of course, expanding educational opportunities for the less well-off seems desirable in the abstract. So too does preventing disparities of wealth from translating into disparities of power (the problem of “domination”). But to say that a society is not just unless educational opportunities are equal, or until “excessive” (whatever that means) concentrations of property and wealth are eliminated, is in effect to say that only a radically egalitarian society can be truly just. Only something approaching absolute equality will do, since where there is inequality at all, and the freedom to do as we will, differences in educational opportunities and concentrations of wealth will emerge. The only way to prevent this is through suspension of freedom and redistribution of assets. No wonder Rawls was circumspect about the rights of property.

The other part of Rawls second principle, the so-called “difference principle,” is also impractical. It states that social and economic inequalities must be “to the greatest benefit of the least-advantaged members of society.” Interestingly, classical liberals and libertarians often justify economic inequality on just these grounds—that the least advantaged members of a free-market economy are, on the whole, better off than they would be otherwise. But Rawls converts an empirical claim (whether it is true is a separate question) into a normative condition: only if inequalities redound to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged are they just.

It is not clear to me that justice requires any such thing. But if it did, I wonder how anyone could know if the condition were actually met—either in the aggregate or, much more problematically, in particular transactions and investments of one’s time, energy, and material resources. Rawls’s method is to show that his “difference principle” would likely be recognized as more just than only one contender: the utilitarian principle of average utility. Perhaps he is right. But the difficulties of ensuring that all economic transactions redound to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged are legion. It could be done, perhaps, through regular redistribution at the end of fixed periods. But how could we know in advance that the least advantaged are in fact better served under a system of redistribution than they would be, longterm, under a system of economic freedom? As von Mises has famously argued, the amount available to distribute over time depends on the system in which wealth is created. Redistribution may well have negative consequences for wealth creation.

By the same token, how could we know in advance the effects that redistrubtion might have on entrepreneurial creativity and innovation, once these have been severed from the hope of a full reward?

Building on the Ruins

A fascinating feature of Rawls’s mature theory is the extent to which it contains elements that support a much more “liberal” theory (in the classical sense) of limited government and individual freedom. As a way of concluding my account of Rawls’s legacy, I want to catalogue these elements and show where I think they point.

Rawls rightly understood that the challenge of liberal regimes is to maintain peace, order, and a sense of legitimacy in the face of three fundamental conditions: a commitment to individual freedom, a commitment to formal equality, and the presence of reasonable pluralism. American political writers and actors still have much to learn from Rawls on this point. We cannot fight or trick our way into political unity and the collective pursuit of substantive moral visions. Rawls noticed something more, which is that regimes where these three fundamental conditions obtain cannot, technically speaking, be understood as “communities” or “associations.” They are rather a distinct kind of human relationship, “political relationship,” where, because of pluralism, controversial moral purposes cannot be pursued without violating freedom and equality. Politics should thus be non-purposive to the greatest extent possible.

Rawls also understood that unlike communities and associations, which are voluntary (e.g., can be entered into and exited at will) political relationship is compulsory: there is no easy exit. He simultaneously understood and worried about the fact that “political power is always coercive power.” And he then drew the right conclusion from these facts: The coercive use of the state to pursue controversial ends in a situation where citizens have no exit is, on the face of it, “incompatible with basic democratic liberties.” So much for the modern progressive agenda.

I would mention one other element of Rawls’s theory that I think is fruitful for future liberal theorizing, though I recognize that it will be more controversial than the points above. Rawls presents liberal political relationship fundamentally as a form of cooperation, not competition, much less war. He offers no justification for this basic starting point of his thought. And, of course, he goes on to use the idea of cooperation in order to press for an egalitarian society, which I have already shown violates freedom and equality. Still, like Rawls, I regard cooperation as the best way to understand and practice liberal politics.

The tacit understanding held by most American political actors today is that politics is war. The goal is to win and wield the power of the state in pursuit of one’s own moral vision—enemies be damned. This, however, will not work in a pluralist society committed to freedom and formal equality. A better way to understand politics is as an ongoing negotiation of truce among citizens who may differ radically and yet remain committed to living together in peace. Cooperation need not mean distributive justice as it does for Rawls; but it can and should mean a commitment to recognizing each other formally as political equals.

A corollary of this understanding of politics is that the use of national power should be limited to purposes about which all, or nearly all, citizens agree. Greater power can, of course be exercised at more local levels of government where “exit” is easier and pluralism less marked; or by voluntary organizations operating on a small or a large scale, as social problems require. But national power, as a matter of moral principle, should be limited to purposes upon which most citizens can agree.

In the end, then, I find in the remnants of Rawls’s political theory the grounds for a classical-liberal theory of politics, rich in associational life and restrained in national pursuits. It seems unlikely that the U.S. will head in this direction anytime soon, but it is a direction I would regard as just.