Governance at elite universities is insular, unaccountable, and marred by conflicts of interest that distract from the pursuit of truth.

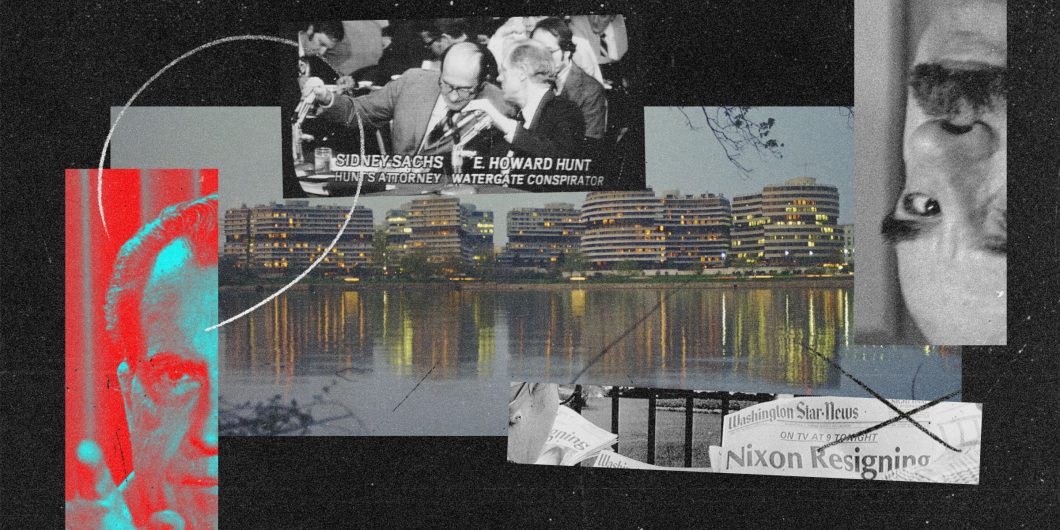

Nixon's Revenge

It’s been a long time since Watergate. For its 25th anniversary, I wrote a book with Peter W. Morgan, originally titled Nixon’s Revenge, on one of Watergate’s most toxic legacies, the proliferation of “ethics rules” and ethics authorities that in practice do anything but promote ethical behavior in government. (The publisher chose a less-provocative title, The Appearance of Impropriety, instead, which I still think was a mistake.) But now 25 more years have passed, and I will not be producing another book. Instead, I offer a few thoughts on Andrew McCarthy’s 50th-anniversary retrospective.

McCarthy’s central claim is that the correlation of forces in 1972 was such that Nixon’s fate was sealed once the process was in motion. I think this is largely indisputable. (Nixon might still have survived had he not passed over one Mark Felt, the number three man at the FBI, in choosing a director to replace J. Edgar Hoover. The aggrieved Felt became the real-life “Deep Throat,” feeding information to Washington Post reporters Woodward & Bernstein.)

It is difficult for people accustomed to today’s media environment to appreciate what a monoculture the media was back then, in that pre-Internet, pre-Cable, pre-Limbaugh era. The press still pretended to be neutral and objective, and was determined enough to maintain that pretense that it would at times even actually be so. There were more limits to what the ruling class was willing to tolerate, in terms of peculation and revealed dishonesty among its own, than there are today. There was in some ways more tolerance for opposing views, with people like William F. Buckley and Billy Graham receiving respectful hearings on mainstream programs in a way that would be impossible today.

But ultimately, that tolerance—and even the ruling class self-policing—was the product of deep-seated security in power. The liberal establishment of that era, which had crushed Sen. Barry Goldwater’s campaign like a bug, saw no one who might challenge it.

This is why Nixon’s election was so traumatic for them. Like Donald Trump’s 2016 victory over Hillary Clinton, the election of a Republican seemed somehow fundamentally wrong. Republicans in Congress could do things, and could even occasionally snatch a short-lived majority. But after four Roosevelt inaugurations, and a string of Democratic presidents interrupted only by Dwight Eisenhower, who could have had the nomination of either party and who showed no inclination to interfere with the post-New Deal federal gravy train, the presumption was that the Executive and the bureaucracy would stay essentially Democratic forever.

Then, Nixon. Not the Camelot-redux hoped for with Bobby Kennedy, or even the party-establishment regime promised by Hubert Humphrey, but Nixon. A man from a small college instead of the Ivy League, a sometimes-awkward introvert, a fervent anti-communist when anti-communism was seen as declassé, Nixon was very much not our kind, dear.

And, as with Trump decades later, the bureaucracy fought him with a fusillade of leaks directed to its allies in the press. This led to Nixon’s understandable desire to “plug the leaks” and to his deeply unwise decision to do so with an operation run from the White House: The Plumbers.

As Henry Fielding noted, if a man lays the foundation of his own ruin, others will be all too apt to build on it, and so it was with Nixon. McCarthy is right that political scandals are first and foremost political, and only secondarily scandals. Lyndon Johnson, Nixon’s predecessor, had spied on his political opponents to the extent of bugging Barry Goldwater’s 1964 campaign plane, but no one cared. Nixon’s “third rate burglary,” on the other hand, became the biggest political story of a lifetime.

As McCarthy also observes, the discussion was one-sided. Senator Sam Ervin (D-NC), previously known as a defender of Jim Crow and segregation, was transmogrified into a hero of the Constitution as he pontificated in front of the TV cameras as chair of the Senate Watergate Committee. (CBS even released a Sam Ervin album, featuring recordings of him telling stories, and even a track of him singing Simon & Garfunkel’s Bridge Over Troubled Waters, which was also released as a single. At least, unlike disgraced former New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, he didn’t receive an Emmy for his TV appearances.) United States District Judge John Sirica was similarly lionized, though without the record deal, as he ruled in favor of aggressive special prosecutors again and again under unprecedented circumstances.

Of course, the press turned themselves into heroes. After Woodward and Bernstein were beatified—and glamorously portrayed by Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman in All the President’s Men—journalism went from a blue-collar trade to a white-collar profession as graduates from elite colleges flooded in. It became clear that the way to get ahead in large media organizations was to investigate and publish stories that helped Democrats. The combination of upscale college graduates and the desire to get ahead by helping Democrats shaped today’s press in many ways.

As with the alternative media, developing some degree of parity in the tech world is essential if conservatives are to withstand attacks from the progressive apparatus.

Ironically, this shift also empowered the opposition press. When it was possible to at least pretend that large media outfits reported on events based solely on whether they were “news,” many people even on the right were content to rely on the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the three TV networks. But now the major outlets suffered from a kind of tone-deafness as they increasingly became monocultures of elite opinion, whose staffs had increasingly similar backgrounds and outlooks. This created a market for alternatives, which started to appear.

First talk radio, which played a major role as opposition press under the Clinton presidency, then Fox News, followed by a constellation of blogs, online video producers, and social-media stars, ultimately producing a formidable counterweight to the “mainstream” media. This was very important, and showed its power in allowing Trump to resist the unending efforts to neutralize him, efforts that started before he was even sworn in.

McCarthy is right that Nixon was outnumbered and outgunned in a way that a modern Republican president would not be. But it’s also true that the “media” world has expanded, and that in this larger universe, which includes tech and social media companies, things are looking as one-sided as in 1972.

As I write this, for example, it turns out that Google was overwhelmingly redirecting GOP campaign emails to users’ spam folders, while allowing Democratic emails to pass through. Researchers found that over 77 percent of GOP emails were diverted to spam, as compared to approximately ten percent of Democratic emails. Furthermore, the percentage of Democratic emails sent to spam stayed level throughout, while the percentage of GOP emails climbed as election day drew nearer. More notoriously, social media like Facebook and Twitter blocked the New York Post’s—accurate—reporting about damning emails found on Hunter Biden’s laptop, with Twitter going so far as to ban users from sharing the stories via direct message.

Much of it wasn’t secretive. In fact, the perpetrators bragged about their efforts afterward. As Time magazine reported shortly after the 2020 election, a “cabal”—Time’s word—of “left-wing activists and business titans” pushed mail-in voting, sponsored protests, moved to block election fraud suits, and employed social media censorship to mute pro-Trump arguments and amplify anti-Trump arguments.

People on the right may have gained some degree of rough parity—or at least competitiveness—in media as McCarthy argues, but when it comes to tech and social media platforms the left dominates almost completely. (Hence their outright panic at the thought of Elon Musk acquiring Twitter and offsetting their advantage.) Even five years ago it was possible to think of the tech companies as basically neutral, serving a sort of utility function. No one believes that today, and no one should.

As with the alternative media, developing some degree of parity in the tech world is essential if conservatives are to withstand attacks from the progressive apparatus. Otherwise, as McCarthy correctly notes, the outcomes are almost preordained. How to do that is a topic for another day, but let those on the right—which nowadays just means anyone outside the woke left—take this lesson to heart. And anyone who cares about liberty, or law, should hope that the establishment’s power faces some additional checks and balances.