In an age of postmodern hyper-individualism, Churchill and Orwell’s advocacy of individual liberty isn’t what is most interesting about them.

No Alternative to Vigilance

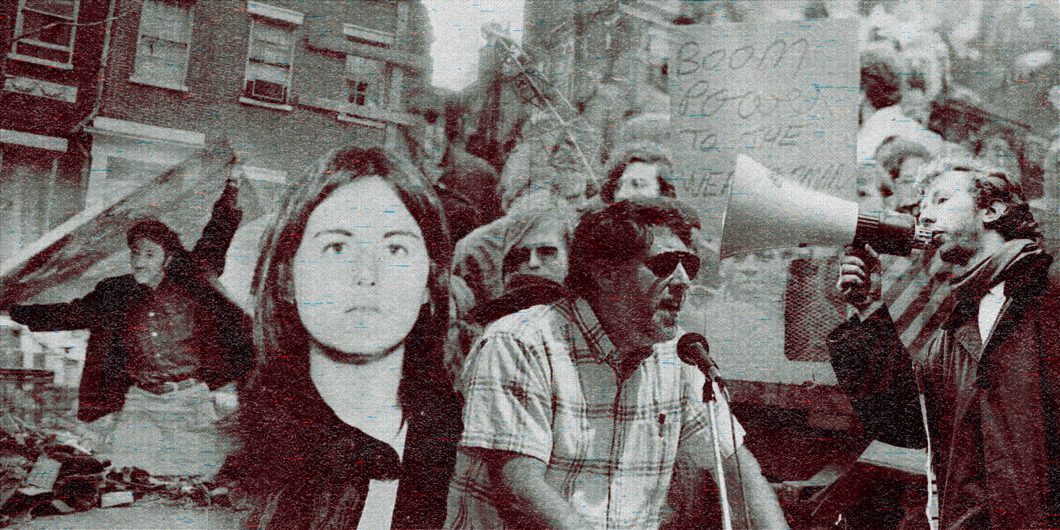

The editor of Law & Liberty asked me to look back at the townhouse explosion, 50 years later. (It has been 51 years since that event, but we’re close enough.) He further asked me to comment on recurring cycles of political violence. Length: 2,500 to 3,500 words. I went to the maximum, and beyond: about 125 words over.

Alan Charles Kors says that I left a lot out. Boy, did I—perhaps more than he knows. Many books have been written about these subjects, and a great many more articles. I have written some of those articles myself. I assume that’s why the editor commissioned me.

Mr. Kors says that I was short on details when it comes to the romanticizers of left-wing militants. I have written pieces on that subject—specifically—including this one from 2012 (“Aren’t They Cute?”).

Every journalist knows that he has to decide, “How am I going to spend my space?” One guy’s decision is likely to be different from another guy’s. I was asked to address a very, very big subject, or subjects. Of the many stories I could have told, I told a few. Of the many facts I could have related, I related a few. Of the many points I could have made . . .

My critics would have written a different piece from mine. No problem.

Mr. Kors further says that I say “nothing new.” My conclusions are “rather unoriginal.” To that, I may plead guilty. There is nothing new under the sun, really. I think most of what we do is repackage, or repurpose, what has been discovered, thought, expressed.

He also accuses me of a “shopworn narrative.” Ah—worn to him, maybe. But my understanding was, I was to write for a general audience, not specialists. Speaking to Alan Charles Kors, I could simply say, “Weather. Townhouse. Brink’s. Bernardine.” These terms are as familiar to him as his own name. But to others?

It’s amazing how time passes. (Talk about a trite observation!) I have many young co-workers—say, 25 years old. They are as distant from the townhouse explosion as I was, at 25, from the premiere of John Ford’s movie Stagecoach. In that essay, I was writing for everyone, or wanting to.

At the end of his piece, Mr. Kors makes a remark about National Review that I don’t understand. But maybe I should say, here and now, that, in my essay, I was speaking for myself, and not my employer. So absolve them, please!

Michael Anton says that I left the impression that the New Left was a New York phenomenon. I plead, again: I was asked to write about the townhouse explosion. It’s not my fault the explosion was in New York. (Same with the Brink’s robbery, in Nyack, about 30 miles north of Manhattan.) If I had been asked to write about the Black Panthers, there would have been a lot of Bay Area in my piece (plus Leonard Bernstein’s party and so forth).

Mr. Anton says I could have written about Chesa Boudin. Oh, could I have—he is a piece unto himself (and there have been a great many). Mr. Anton further says I left out the “most notorious” statement of Bill Ayers. Listen, he has filled his life with such statements—one could recite them ad nauseam.

As he proceeds, Mr. Anton accuses me of a “dodge,” a “pose,” etc. I can assure readers that my views are my views, sincerely held, forthrightly expressed. I’m not dodging anything. Or posing for anything. You may think my views stupid or wicked or what have you—but they are my honest views.

According to Mr. Anton, I have sneaked in an implication, “unspoken but unavoidable.” What is it? “If both sides are to blame, then everyone is, and if everyone is, no one really is.” I promise you, I am a great blame-assigner. It’s hard to out-blame me. I damn—I am the foe of—anyone who menaces law and liberty, no matter who he is. I don’t care what tribe he belongs to, what jersey he wears. We are all responsible for our actions.

(All my career, I have been accused of judgmentalism. To be accused of shrinking from judgment is a new experience. So maybe there is something new under the sun.)

There will always be people who want what they want, when they want it, and are willing to use their fists, or guns, or bombs, to get it. To eternal vigilance, there is no alternative, as I see it, wearying though such vigilance may be.

The phrase “law and liberty” reminds me: I once asked Robert Conquest how he would describe himself—what label he would put on himself, if he had to. He said that “Burkean conservative” would do. He also said that Orwell had spoken of “the law-and-liberty lands.” So he, Conquest, would be pleased to be known as a “law-and-liberty man.” I know just what he means.

Back to Michael Anton’s piece: For anyone who wishes to know about January 6, there is ample video evidence, plus more than 300 arrests, with corresponding court cases. As to what groups and individuals pose a threat to the country, I rely on such officials as the secretary of homeland security and the FBI director, who I believe know.

Mr. Anton says that my piece “ends with the laziest and hoariest faux-comparison of all: Kristallnacht.” I did not think I was making a comparison, faux or vrai. I trust that most readers could understand me. My point was—unoriginal, to be sure (and no less true for that)—the fragility of civilization. I have spent a fair chunk of my life working in Salzburg. You never saw a more peaceful place. It seems like the safest, most civilized spot on earth. But within living memory, it was the site of an explosion of savagery—which people should be on guard for. There will always be people who want what they want, when they want it, and are willing to use their fists, or guns, or bombs, to get it. To eternal vigilance, there is no alternative, as I see it, wearying though such vigilance may be.

Finally, Mr. Anton despairs that “the right” may be represented by the likes of me. He can rest easy. To say it again, I represent no one but myself, which is a hard enough job. I recall a line from our ancient history. It was uttered in a romantic context, but it applies to others: “Why don’t you speak for yourself, John?” That is the best many of us can aspire to do: speak for ourselves. And let others pile on as they will.

Harvey Klehr mentions Bill Ayers and his academic standing (as do other respondents). Readers may like to know something additional—one of the many, many things I left out of my essay, in deciding how to spend the space.

When Ayers announced his retirement from the University of Illinois at Chicago in 2010, he was up for emeritus status. He was denied it after an impassioned speech by the chairman of the university board, Christopher G. Kennedy.

In 1974, Ayers and other Weathermen put out a book called Prairie Fire: The Politics of Revolutionary Anti-Imperialism. It was dedicated to a long list of “revolutionary” figures—over 200 of them—including Sirhan Sirhan, assassin of Robert F. Kennedy, Chris’s father.

In his piece, Will Morrisey writes, “Where does morality come from? For centuries, of course, the answer was ‘God.’” This jogged a memory in me. Some will know what I’m about to relate, but I offer it for a general audience. And even some who know it already will perhaps not mind hearing it again.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was born in 1918, a year after the Bolshevik Revolution. When he was growing up, he heard old, simple people say, “This all happened because the people forgot God.” Solzhenitsyn was a very brainy kid. He thought this talk was kind of silly.

For 50-plus years, he studied Communism and endured it. And in his full maturity, he concluded that he could not improve on what those old, superstitious people had said in his youth: “This all happened because the people forgot God.”