Populism is shot through with the search for nobility, whether in farm animals, vegetables, cakes, sneakers, hubs and engines, or human talents.

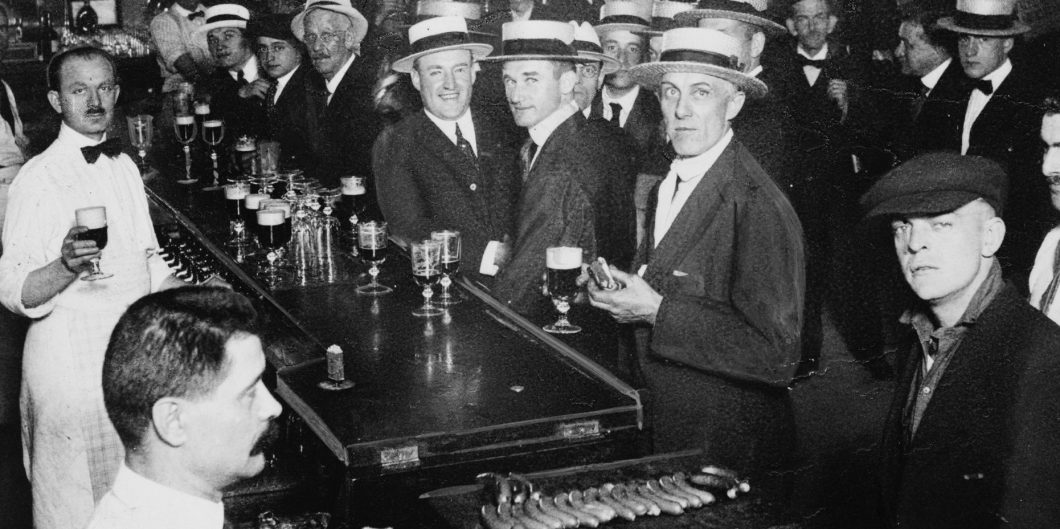

Prohibition, Liberty, and Responsibility

When Law & Liberty invited me to write about Prohibition on the one-hundredth anniversary of the Eighteenth Amendment and the Volstead Act, I snatched at the opportunity. I was honored to have been asked, and now I am doubly honored to acknowledge three excellent responses to my essay that are far more coherent than my original contribution to this discussion. William Atto, Sean Beienburg, and Scott Yenor have broadened and deepened my knowledge of Prohibition in fact and theory, and they have given me more avenues for investigation.

My interest in war, religion, and reform goes back many years. In 2003, I published The War for Righteousness, an attempt to understand and explain how the liberal Protestant clergy in the United States either reconciled themselves to American intervention in the Great War in 1917 or, in many cases, embraced or even ratcheted-up the extravagant Wilsonian promises about the possibilities of a war of redemption. An explanation was necessary, I argued, because so many of these clergy had for decades prior to the war promoted international peace and brotherhood. How did professional peace advocates become hardcore interventionists and then uncompromising advocates of total war against Imperial Germany willing to pay almost any price for total victory? The short answer was that their social gospel theology, broadly construed, had predisposed them to mobilize their churches for the greatest crusade ever, seizing the opportunity the war handed them to continue their transformation of historic Christianity and apply the social gospel in their concerted effort to remake America and the world. In hindsight, their optimism strikes us as delusional, but they were in earnest and thought they stood at the moment of fulfillment for their grandest aspirations. The liberal clergy were not “co-opted” by the government for the war effort. They were “self-mobilized” and enlisted themselves for the duration and beyond for seemingly endless domestic and international wars for righteousness.

The push for national Prohibition that culminated in 1919 opens another window into this same moment of American history, and my essay for Law & Liberty gave me an opportunity to revise my earlier argument, although I did not do so explicitly. I was initially asked to write about the war and prohibition and how war metaphors have become a habit that has proven hard to shake. Since I study mostly religion and war and religion and politics, it was natural that my thoughts turned first to religion’s role in pushing prohibition to its sweeping victory. Religion’s role in launching temperance and then prohibition crusades in the early nineteenth century is well known. What is less well known is religion’s role in securing victory in 1919 and religion’s role in sustaining enforcement and in lobbying Congress not to modify the Volstead Act in the 1920s. While Jewish and Catholic leaders participated in the campaign for prohibition, what I mean here by “religion” is a particular brand of Protestant activism. And I don’t mean religion as an abstract force. The combination of war, religion, and reform was the product of the activity of thousands of flesh-and-blood human beings. Contrary to the impression I left in The War for Righteousness, such activism was not confined to the liberal clergy but characterized a broad evangelicalism that united modernists and fundamentalists in a common cause.

Among all the other things Prohibitionists allied themselves with—anti-immigration, anti-Catholicism, social control, industrial and labor reform, scientific efficiency, and Progressive reform in general—they also drew strength from an activist Protestantism that promoted Christianity largely in terms of cultural transformation rather than preparation for the life to come. In other words, the way reformers judged whether or not the church was fulfilling its task in the world was the degree to which it succeeded in shaping American politics, economics, law, war, and foreign relations.

Evidence for this abounds in religious periodicals, in the minutes of denominational committees and national assemblies, in the work of the Anti-Saloon League, in testimony before the House and Senate, in sermons and special worship services devoted to Prohibition, and in the “secular” speeches of politicians. The fusion of war, religion, and reform could not be clearer in these sources. Whether all this enthusiasm proved necessary to the complicated and drawn-out process of ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment and passage and enforcement of the Volstead Act is hard to say. What is unmistakable, however, is that a large number of leaders believed it was so or at least wanted their constituents to believe it was so. Prohibition’s victory seemed to vindicate Christianity’s calling and capacity to remake America and the world. For countless Americans, Prohibition was a religious triumph achieved through politics, war, moral pressure, and innovative theology.

It is equally important to understand that Prohibition divided American Christianity—as it had done since the beginning of the movement in the 1820s. Prior to that time, drunkenness had been denounced as a sin condemned by both the Old and New Testaments. Wayward clergy and parishioners faced church discipline for abuse of alcohol. But wine was welcomed as a blessing from God, affirmed by Jesus, central to the sacrament of Holy Communion, praised by John Calvin and many other theologians influential in American Protestantism, and an honored part of conviviality, including celebrations accompanying the ordination of pastors. Prohibition marked a revolution in American Christianity. Alcohol in and of itself became evil to the point of even being removed from the sacrament. The effort to nationalize total abstinence culminated during the First World War, as I sketched out in my essay. And the effort mobilized a Christian opposition that for theological, ecclesiological, moral, and political reasons fought to sustain the older tradition of biblical exegesis, to preserve the apolitical character of their pulpits and the separation of Church and State, to resist the social gospel, and to preserve personal liberty and limited government.

The religious history of the prohibition movement from beginning to end needs to be written, and Law & Liberty has inspired me to undertake that task. As I explore religion’s ongoing role in the movement (and against the movement), I need to avoid isolating religious arguments from everything else at play. William Atto’s reminder is well taken that the prohibition movement was embedded in a web of nationalism, nativism, and campaigns for social justice more generally, and in light of his last point I will need to show that it was the reinvention of Calvinism rather than Calvinism itself that energized the crusade for a dry America. On the whole, it was the New School Calvinists in the 1830s–those who liberalized doctrine, embraced revivalism and other “new measures,” and mobilized the faithful for organized benevolence–who agitated for total abstinence. Indeed, some of the most stubborn anti-Prohibitionists came from the ranks of orthodox Calvinists.

Sean Beienburg’s provocative “one cheer” for the Eighteenth Amendment offers an important reminder that the constitutional culture of 1919 is not the constitutional culture of 2019. It is indeed striking how the promoters of the amendment and those charged with its implementation upheld the need to actually go through the amendment process, acquire the consent of the states, and adhere to their oaths of office. The question will be whether the religious prohibitionists showed the same scruples about law and procedure. The statements of the PCUSA, the Federal Council of Churches, Methodist bishops, and others—especially in their open contempt for federalism and blithe dismissal of personal liberty, suggest they retained few such scruples. Many of them were nationalists who venerated the modern State.

Scott Yenor’s “one cheer” for Prohibition, though coming from a different corner of the pub from Beienburg’s, adds an important caution against a doctrinaire libertarian answer to the problem of alcohol abuse and affirms law’s capacity to shape public morality. While it is true, however, that Prohibitionists “fought against intemperance in the name of achieving greater self-control,” it is also true that they fought for much more. They fought for social control, first in their churches, then through local restrictions and shutting down saloons, and then through state and national action to ban the manufacture, distribution, importation, and sale of alcohol.

The question in 1919, and before and since, was whether such sweeping attempts at social control promoted responsible citizenship or actually undermined the older ethic of self-control and personal character and thereby weakened the cause of personal liberty and responsibility.