John F. Pfaff’s Locked In: The True Causes of Mass Incarceration is probably the best book on so-called mass incarceration to date.

Rawls, Religion, and Judicial Politics

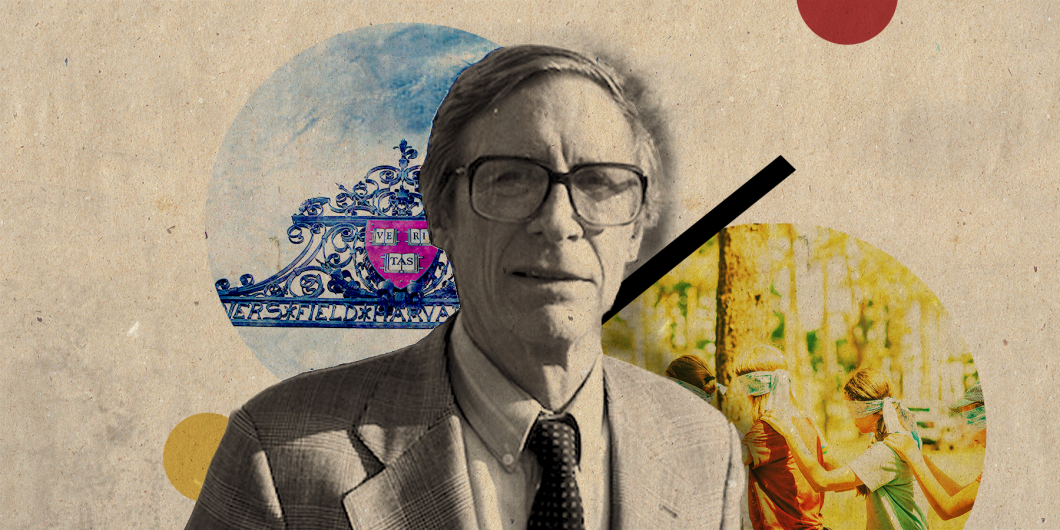

In recognition of the fiftieth anniversary of A Theory of Justice, David Corey offers us a succinct and readable summary of John Rawls’s work as it developed and matured. Had Rawls been as lucid in presenting his own ideas, he may have enjoyed a cultural popularity to match the esteem once paid him within the academy.

As it is, a half-century after the initial splash of Rawls’s famous book, Rawlsian embers are fading within the humanities except in a few dusty corners of philosophy departments. The only discernable flames come from law schools where the focus is on Rawls’s later work, such as Political Liberalism, rather than the more systematic Theory. There are reasons for this, and Corey’s focus on Rawls’s so-called political turn moves us a good deal of the way toward a clear-headed understanding of Rawls’s legacy.

As Corey correctly points out, scholars have disagreed on why Rawls decided to recast his theory. But Rawls was clear enough in explaining his rationale. He came to see that Theory went too far in expecting citizens to adopt a neo-Kantian understanding of the good. In what follows I would like to make three suggestions about Rawls’s political turn as a follow-up to Corey’s essay. First, Rawls’s political turn was a sincere if misguided effort to make his theory attractive to religious Americans, particularly Christians. Second, Rawls’s political turn necessitated a more politically active Supreme Court. Finally, and here I slightly depart from Corey, even after his political turn, Rawlsian peace assumed not only the achievement of social egalitarianism but also popular acquiescence to egalitarian principles.

Rawls and Religion

As a young man preparing to graduate from Princeton, Rawls wrote a senior thesis entitled “A Brief Inquiry into the Meaning of Sin and Faith,” in which he defended the notion of a just society drawn, if imperfectly, from the teachings of Christianity. At this point in his life, Rawls was a fairly devout Episcopalian seriously considering the priesthood. Instead, he enlisted in the Army and fought in the Pacific during World War II, an experience that caused him to lose his faith.

Despite his agnosticism, Rawls retained a profound commitment to social justice. No longer animated by the Gospel, Rawls turned to Kantian political theory. After earning his Doctorate in Philosophy, also from Princeton, he labored tirelessly writing Theory, hoping to provide a philosophic groundwork for a more just America. But to his dismay, several sharp minds recognized the inconsistency between his principle of liberty and his insistence upon Kantian ethics. Political liberals of various stripes may have been willing to overlook the contradiction, but many religious Americans were decidedly recalcitrant in opposing Theory. Any chance of political success required winning over this significant portion of the American populace.

Rawls might have been too subtle on this reason for recasting his theory in the original publication of Political Liberalism, but not so in the paperback edition with its new, more overt Introduction. He explains there that the book’s basic question should be understood as follows: “How is it possible for those affirming a religious doctrine that is based on religious authority, for example, the Church or the Bible, also to hold a reasonable political conception that supports a just democratic regime?”

The answer to this question, Rawls says, does not admit of philosophic specification. The reasons for accepting the principles of justice are no longer associated with any conception of the good life. If citizens wish to connect the principles to a conception of the good, they are welcome to do so as a matter of private opinion—whether on their own or as part of a larger subgroup of American society—but they cannot insist upon this connection publicly. He hopes the principles will be accepted widely as an “overlapping consensus” of several conceptions of the good, including religious conceptions. Only public arguments drawn from this consensus are legitimate; such arguments are based on “public reason.”

An example of public reason Rawls finds consistent with his recast theory is Mario Cuomo’s 1984 lecture at Notre Dame University on abortion, which Rawls favorably cites. In that speech, Cuomo argues that as a Catholic he believes abortion is wrong, but because not all Americans share his faith, he would not use his political power to impose a ban on abortion. Rawls hopes this becomes the normal attitude of all Americans, religious or otherwise.

Rawls’s approach, however sincere it may be, is ultimately misguided. Cuomo’s position on abortion clarifies the problem. First, Cuomo assumes religion offers little in the way of public goods, and that churches are merely private organizations that serve the apolitical needs and desires of individuals, such as spiritual comfort. In this view, a church that enjoins members to observe certain moral teachings does so as a club rule rather than a universal precept. Second, and relatedly, Cuomo gives the impression that policy positions that correspond to faith cannot be publicly defended, suggesting an incompatibility between faith and reason. Following Cuomo’s logic, Rawls would severely truncate legitimate public reasons for laws to terms recognized and approved by the amorphous idea of an overlapping consensus, which is meant to exclude not only claims of faith but also some principles of reason that are not widely embraced or that appear religious in nature. It is not clear why Christians would join Rawls in applauding the Cuomo approach. Nor is it clear who will define the overlapping consensus and the boundaries of public reason.

Enter the Supreme Court

The attempt to bring religious Americans under the tent of political liberalism required Rawls to defend a broader conception of judicial review than anticipated by the American Founders. For Rawls, citizens and lawmakers cannot be trusted to decide which arguments count as public reasons and thereby acceptable justifications for laws, for they always will be tempted to decide the matter in their own favor. What is needed is an institutional check that ensures public arguments are in fact “reasonable,” which is to say consistent with the public conception of justice. And that institution is the Court.

Even if judges remain generous and allow for a broad array of public justifications, the fact that they would be policing what people say in defense of public policy is itself a violation of the Founders understanding of constitutional republicanism.

Rawls does talk about judicial review in Theory, but not nearly to the extent that he does in Political Liberalism. Corey is right when he says that legitimacy is crucial to Rawls’s later thought; and what makes a law legitimate for Rawls is not its adherence to the U.S. Constitution, but its justifiability using publicly available reasons. As the Founders give the Supreme Court the role of determining what is constitutional as a matter of law, so too does Rawls wish the Court to play this role in his system; although, he would extend their authority to determine whether public arguments are consistent not only with the text of the Constitution, but also with the principles of political liberalism that he hopes will forge an overlapping consensus.

One of the most revealing passages in this regard comes from Rawls’s posthumously published Lectures on the History of Political Philosophy. In the Introduction he writes:

Since liberalism endorses the idea of democratic government, it would not try to overrule the outcome of everyday democratic politics. So long as democracy exists, the only way that liberal philosophy could properly do that would be for it to influence some legitimate constitutionally established political agent, and then persuade this agent to override the will of democratic majorities. One way this can happen is for the liberal writers in philosophy to influence the judges on the Supreme Court in a constitutional regime like ours.

Rawls makes clear that normally legislative decisions should stand unless there are clear questions of constitutional legitimacy, in which case he favors the use of judicial review. But whereas someone like Alexander Hamilton or John Marshall would defend judicial review as a way of upholding popular will as expressed in the Constitution, Rawls champions a form of living constitutionalism that upholds the principles liberal theorists, like himself, believe should be expressed in popular will. Neo-Kantianism sneaks in through the backdoor!

Peace, Justice, and Friendship

Corey makes an interesting move in using Rawls’s theory to help us think about the challenges facing classical liberalism. Though heavily influenced by Kant and Hegel, Rawls also learned from Locke, Mill, and others eager to defend individual liberty and toleration. But freedom and toleration have limits for Rawls, and few classical liberals would be satisfied with the perimeter Rawls sets; nonetheless, Corey is right that Rawls’s theory is an occasion for thinking about the health of our polity.

Usefully, Corey turns to the question of war as a way of gauging our political health. It is certainly true that Rawls hopes to provide a framework for pluralistic cooperation, and that he seeks a language for fostering mutual recognition of citizens as moral agents who must make rational laws for a diverse group of people. But Rawls’s own standard for political health has far more to do with equality than it does with the avoidance of war. Thus, one must squint a bit to follow Corey down this path.

But the squint is well worth it, if only because avoiding war is a more obvious purpose of political life than achieving near perfect substantive equality. History affords ample examples of regimes that have succeeded in establishing lasting peace without political or economic equality. I know of no regime, however, that has managed to achieve the type of equality Rawls demands as a condition of justice. Those that have tried have not only failed, but also have destroyed freedom in the process—and peace without freedom is like a kitchen without food or a library without books. No one would give up a child for the sake of obtaining a nursery.

With both eyes open again, I don’t see enough evidence to say with Corey that Rawls offers us a meaningful theory of political cooperation that avoids war. Rather, it looks to me that Rawls is far more concerned with political victory in the public policy arena than he is with establishing a framework for peaceful cooperation. Yes, he wants peace, but only after the achievement of an egalitarian regime in which his two principles of justice inform all laws. He will allow religious people to participate in governance so long as the government acts without consideration of religious belief. And while religious leaders are barred from trying to influence the outcome of even ordinary law, liberal theorists are given a green light to influence the judges that determine the outcomes of constitutional politics.

And if these judges are in fact trying to be true to Rawls’s spirit, we should expect the range of publicly acceptable arguments to be narrowed, perhaps severely. Even if judges remain generous and allow for a broad array of public justifications, the fact that they would be policing what people say in defense of public policy is itself a violation of the Founders understanding of constitutional republicanism.

The best path toward the type of classically-liberal polity Corey recommends is a rediscovery of the institutional structures we have inherited through the U.S. Constitution. Our frame of government envisions three co-equal branches of government empowered to act upon specific and limited national ends, thereby leaving much for families, churches, and localities to manage in accord with their best understandings of truth and goodness. Nothing in our Constitution demands Cuomo-Christianity or elitist judges.

In addition to constitutional republicanism, political peace requires friendships of all kinds; and by all accounts Rawls possessed the virtues of friendship. He was a faithful husband and father, a scholar who responded generously to many critics, and a committed teacher who cared about his students. These relationships did more to promote peace than anything he wrote. They are his true legacy. We have more to learn from Rawls the man than Rawls the theorist.