In yesterday's 5-4 ruling, the Supreme Court held compelling crisis pregnancy centers to promote abortion violates free speech.

The Constitutional Political Economy of Carcass Disposal

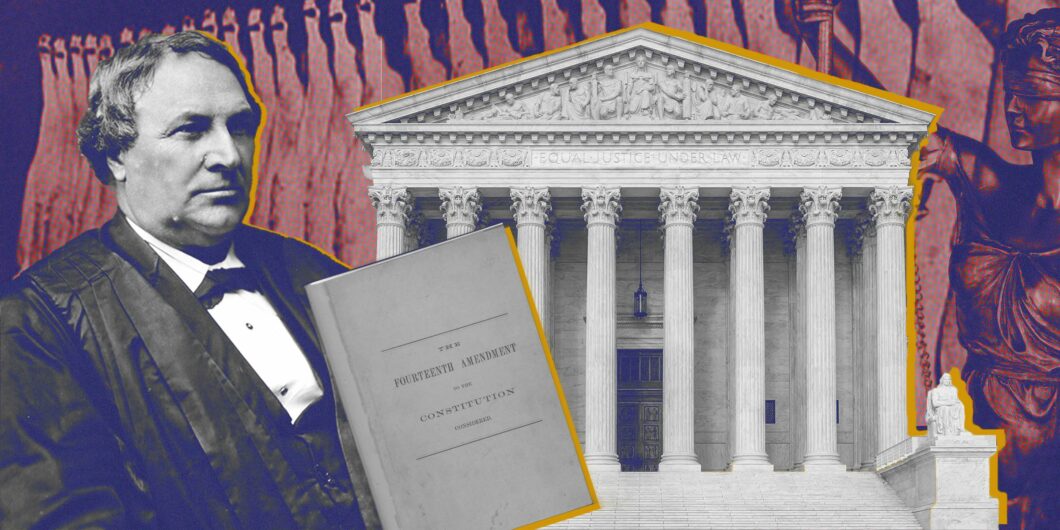

Ilan Wurman has written an engaging essay about the importance of overruling The Slaughter-House Cases without telling readers why they were wrongly decided. I concur in part, dissent in part, and request a supplemental briefing.

Wurman is correct that Slaughter-House rests on an implausible theory of the Fourteenth Amendment and that there is no salvaging its constitutional reasoning—notwithstanding the rehabilitative efforts of Kurt Lash and Judge Kevin Newsom. Lash and Newsom are wrong in two respects—first, in maintaining that the Fourteenth Amendment “incorporates” against the states all and only rights specifically enumerated in the Constitution’s text; second, in reading Justice Miller’s opinion for the Court in Slaughter-House to be consistent with an enumerated-rights theory.

Randy Barnett and I have argued that the original public meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Privileges or Immunities Clause protects fundamental civil (as distinct from political) rights that were widespread and entrenched in the states and associated with citizenship. These rights establish a floor below which states cannot fall; a state cannot unreasonably discriminate in its regulation or protection of them or deny them to everyone. Many of these fundamental rights are enumerated, like those listed in the first eight amendments; others, like the rights to organize and conduct one’s family life, marry, or earn a living, are not. Miller’s bizarre theory of the privileges and immunities of citizenship—which includes the right to access subtreasuries but not the freedom of speech—is not consistent with our fundamental-rights theory or an all-and-only-enumerated-rights theory. When the Court “officially” rejected the incorporation of enumerated rights in United States v. Cruikshank (1875), it followed Slaughter-House’s reasoning.

Wurman is also correct that the Civil Rights Act of 1866 is an indispensable guide to identifying just what sort of rights the Privileges or Immunities Clause protects. We have some important differences, however, concerning the details.

The Thirteenth Amendment Argument

Wurman mentions the butchers’ Thirteenth Amendment challenge to the slaughtering monopoly at issue in Slaughter-House only in passing. The challenge might seem self-evidently ridiculous and indeed outright insulting. A group of White butchers, invoking an Amendment that was designed to liberate enslaved Black people, against a monopoly that—whatever might be said against it—certainly wasn’t part of a scheme to maintain a racialized underclass? Come on.

To be clear: The Court was right to reject the Thirteenth Amendment challenge. But there’s more to this challenge than the Court seems to have believed, and the short shrift that Slaughter-House gave to it anticipated truly egregious errors in future cases.

Wurman isn’t alone in referring to the Fourteenth Amendment as a means of constitutionalizing the Civil Rights Act of 1866. I’ve done it myself. But I’ve since reconsidered the language of constitutionalization. Why? Because most Republicans did not regard the 1866 CRA as requiring further constitutional authority. In this regard, Illinois Senator Lyman Trumbull—the constitutional witness whom Wurman most often calls—is representative.

The 1866 law was enacted by a Republican-dominated Thirty-Ninth Congress over President Andrew Johnson’s veto before the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified. In overriding Johnson’s veto, Republicans rejected Johnson’s arguments against the CRA’s constitutionality. Trumbull was among them, and made plain his belief that the Thirteenth Amendment provided sufficient constitutional authority for the 1866 CRA—and the Second Freedmen’s Bureau Bill proposed alongside it.

For Trumbull, the Thirteenth Amendment did not just abolish slavery and involuntary servitude (subject to a narrow exception for penal servitude that Democrats exploited). It empowered Congress to define citizenship; secure civil rights; attack what he referred to as the “incidents of slavery” and “badges of servitude”; and prevent formerly enslaved people from being driven into dependence as a result of destitution.

Together, the 1866 CRA and the Second Freedmen’s Bureau Bill express the constitutional political economy of Reconstruction Republicanism. Reconstruction Republicans—like Jacksonian Democrats, like Jeffersonian Republicans—didn’t draw sharp distinctions between “economics” and “politics” and didn’t believe that the Constitution was silent concerning questions of wealth accumulation and distribution. The transition from slavery to full citizenship for millions of forced laborers whose general strike made possible a Union victory required massive economic redistribution. Having smashed a system of racialized hyper-exploitation, Republicans were committed as well to fostering economic independence. That’s why the Second Freedmen’s Bureau Bill authorized the distribution of food and clothing, tasked the Bureau’s Education Division with constructing and staffing common schools, and funded and authorized the Bureau’s Land Division to purchase and reserve unoccupied public lands for destitute “loyal refugees and freedmen.”

Of course, the distance between a Lyman Trumbull and a Thaddeus Stevens (who favored the confiscation of enslaver’s estates) was substantial, and the precise measure of that distance was controversial. What cannot fairly be disputed is that Reconstruction Republicans generally considered that they had the constitutional power under the Thirteenth Amendment to define citizenship and protect fundamental civil rights associated with citizenship. Or that most of them believed that the Thirteenth Amendment authorized measures providing people with land, education, and other goods and services, with an eye to promoting their economic and political independence. The Fourteenth Amendment didn’t constitutionalize the 1866 CRA or the Second Freedmen Bureau’s Bill; it confirmed their constitutionality.

The reasoning of Slaughter-House was wrong and harmful in many ways, but the decision should not be reversed.

This isn’t a mere quibble. Justice Miller’s dismissal of the butchers’ Thirteenth Amendment argument in The Slaughter-House Cases anticipated the gutting of Reconstruction and the enabling of Jim Crow segregation. When Justice Bradley asserted for the Court in the so-called Civil Rights Cases (1883) that it would be “running the slavery argument into the ground” to “declare that, in the enjoyment of the accommodations and privileges of inns, public conveyances, theatres, and other places of public amusement, no distinction shall be made between citizens of different race or color or between those who have, and those who have not, been slaves,” he drew upon Slaughter-House. And so the Court held unconstitutional provisions in the 1875 Civil Rights Act that prohibited such distinctions, determining that Congress could not reach them under the Thirteenth or Fourteenth Amendments.

A decade later, the Court in Plessy v. Ferguson (1893) relied upon Slaughter-House Cases in rejecting a Thirteenth Amendment challenge to segregated railcars, proclaiming it “too clear for argument” that the Amendment didn’t apply. Finally, the Court in Hodges v. United States (1906) held that the Thirteenth Amendment did not authorize the federal prosecution of a group of White men who took up arms against eight Black workers and drove them away from an Arkansas sawmill. Justice Brewer wrote that it was “as clear as language can make it” that the Thirteenth Amendment covered only “subjection to the will of another” and that “no mere personal assault or trespass or appropriation operates to reduce the individual to a condition of slavery.”

Justice John Marshall Harlan was the lone dissenter in the latter three cases. He maintained that the Thirteenth Amendment “invested Congress with power, by appropriate legislation, to protect the freedom thus established against all the badges and incidents of slavery as it once existed.” These badges and incidents included those listed in the 1866 CRA but were not limited to them. They encompassed “all rights fundamental in … freedom and citizenship,” which Harlan insisted could not be left “at the mercy of corporations and individuals wielding power under the States.”

Harlan was right. Slaughter-House’s brisk assumption that the Thirteenth Amendment prohibited only systems of subjugation that approximated African chattel slavery was unduly narrow. Such a narrow conception cannot explain the Reconstruction Republican conviction that the 1866 CRA was fully constitutional, and (together with a similarly narrow conception of the Fourteenth Amendment) did a tremendous amount of harm. Not until the Court in Jones v. Alfred Mayer Co. (1968) upheld under the Thirteenth Amendment legislation barring racial discrimination in the public or private sale or rental of property did the Court come close to capturing Congress’s Thirteenth Amendment powers.

Slaughter-House’s Slaughterhouses

Nevertheless, I don’t think that the butchers should have prevailed in Slaughter-House, under either the Thirteenth or Fourteenth Amendments. Wurman apparently does, and I’d like to hear more about why.

We can say three things with confidence about the Crescent City slaughtering monopoly. First, it wasn’t unusual. States often gave monopoly privileges that included the power to perform state functions—including the protection of public health and safety via the construction of regulated slaughterhouses. No administrative agencies existed to inspect hundreds of privately owned slaughterhouses for regulatory violations, so many cities operated public slaughterhouses. Second, the then-prevailing approach to slaughtering animals in New Orleans generated horrendous health problems involving unrefrigerated fly-covered carcasses and gory waste that it turns the stomach to even read about. Third and finally, the politics that produced the monopoly charter and inspired litigation against it was complex and remain contested.

In his highly influential dissent, Justice Stephen Field struck various chords that call to mind Reconstruction Republican political economy. As Willie Forbath has observed, however, he’s playing a different tune, as evinced by his citation of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations and his comparison of the Louisiana super-slaughterhouse to feudal institutions. Reconstruction Republicans were capitalists, to be sure. But their constitutional political economy couldn’t underwrite the industrial wage-labor that emerged in northern states in the late-nineteenth century, which promised no economic independence for a propertyless proletariat. Rebecca Zietlow has focused attention on the 1868 enactment of a statute limiting the hours of federal workers to eight hours a day. Said Republican Senator Henry Wilson—a leading framer of the 1866 CRA—in support of the eight-hour law: “In this country and in this age, as in other countries and in other ages, capital needs no champion; it will take care of itself, and will secure, if not the lion’s share, at least its full share of profits in all departments of industry.”

Wurman and I apparently agree this much with Field: “[E]quality of right … in the lawful pursuits of life throughout the whole country is the distinguishing privilege of all citizens of the United States.” But this general principle doesn’t decide the case. No right is absolute; all rights can be reasonably regulated; regulations often draw distinctions between people. We have then to consider how to distinguish between reasonable and unreasonable distinctions.

And here’s where Wurman loses me. He declares that “there is simply no justification for ‘rational’ or ‘any conceivable’ basis scrutiny.” But it seems to me that he has recreated a version of the rational-basis review that the Court currently uses to evaluate laws that don’t burden fundamental rights or use suspect classifications. I say “a version” because scholars have long observed that the Court’s “default” rule of judicial scrutiny of government restrictions on non-fundamental liberty rights—rational-basis review—can take two forms. One form—“rationality review”—is deferential to the government but not toothless. The other—“conceivable basis review”—is less a standard of review than a rule of decision that requires victory for the government.

Barnett and I have endorsed rationality review. Rationality review presumes that government action is constitutional. But it requires the government to adduce evidence in support of its assertions that it is pursuing constitutionally legitimate, public-oriented ends. Put differently, the government has the burden of production; the litigant has the burden of persuasion. When Wurman in discussing Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) says that “[w]hether limiting marriage to opposite-sex couples is a genuine regulation or an abridgment will depend on the purposes of marriage,” I expect that he wouldn’t allow a state to assert without any evidence at all that “marriage between same-sex couples harms children.” I’m tempted to say, “Welcome to the club, Ilan.” But I’m not sure whether he wants to sit with us.

Here is where I sit: Slaughter-House reached the right conclusion for the wrong reasons. The right to pursue a lawful calling was widespread, entrenched, and associated with citizenship when the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified. It was and is a fundamental right protected by the Privileges or Immunities Clause. But the monopoly was a reasonable regulation of that right, not a mere pretext for wealth extraction that was calculated to reduce independent artisans to dependent wage laborers. It was an ingenious effort to address a public health crisis in New Orleans. Replacing a panoply of grossly unsanitary small-scale slaughtering operations adjacent to the Mississippi River with a single, price-regulated abattoir in a centralized location to which all butchers had access, fell comfortably within the scope of states’ reserved powers to regulate the rights of some in the interest of the health and safety of all.

The reasoning of Slaughter-House was wrong and harmful in many ways, but the decision should not be reversed. The Civil Rights Cases are another story.