The late Tocqueville scholar Peter Augustine Lawler used to say that Tocqueville believed things were “getting better–and worse–all the time.”

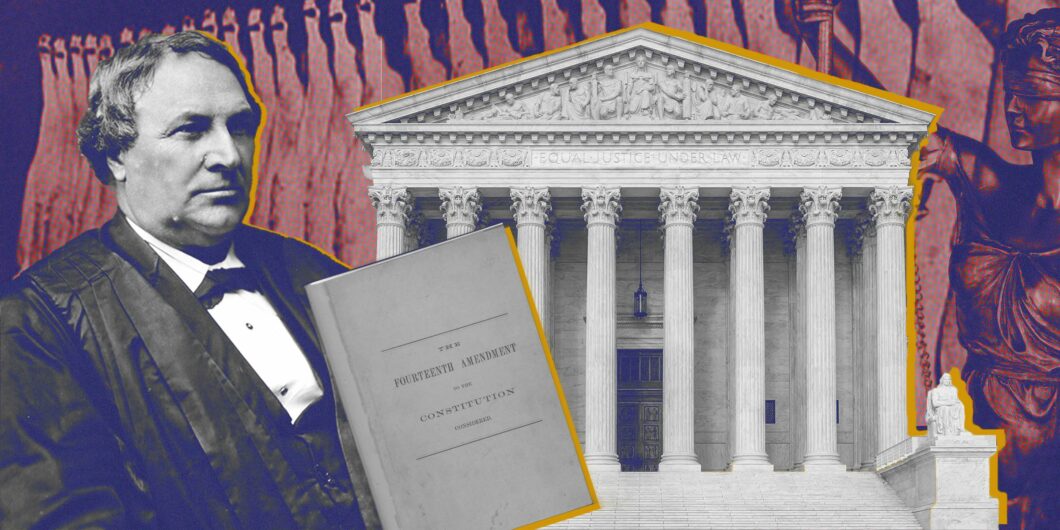

What Would It Mean to Reverse Slaughter-House?

In his lead forum essay, Ilan Wurman argues that The Slaughter-House Cases are “one of the most egregiously wrong Supreme Court cases ever decided,” and that “[i]f the [privileges or immunities] clause were to be properly revived, that would raise serious questions about the modern lack of protection for economic liberties.”

Yes. And no. The answer depends on what part of the decision we’re considering. While a reasonable reading of the 14th Amendment privileges or immunities clause would hold that it does apply to the state-level privileges or immunities, the Louisiana action would not violate the clause even if the Court did apply it in the cases.

The majority in The Slaughter-House Cases asserts what amounts to three separate justifications for finding for Louisiana and against the butchers. They are:

[1] The New Orleans monopoly is a reasonable exercise of the state’s police powers. The majority suggests it would be a reasonable exercise of the state’s police powers even if the 14th Amendment privileges or immunities clause applies to the cases;

[2] The original intent of the 14th Amendment confines it (mainly) to securing the rights of recently freed African-Americans. Protecting the privileges or immunities asserted by the New Orleans’ butchers is outside of the scope of the purposes of the clause;

[3] The national-level privileges or immunities protected by the 14th Amendment do not include the type of privileges or immunities the butchers assert against the Louisiana law, therefore federal courts have no constitutional jurisdiction to set aside the state law.

I’ll start with the last section of the Court’s decision, and briefly note my agreement with Wurman’s criticism of this part of the decision.

The clause states that “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.” The reference to “citizens of the United States” in the clause most reasonably only identifies the set of individuals—US citizens—whose privileges or immunities states cannot abridge. It does not, as the majority in The Slaughter-House Cases strains to read, identify a narrow set of specifically national-level privileges or immunities that states cannot abridge relative to a much broader set of state-level privileges or immunities which the Amendment leaves untouched.

The Court’s reading of the clause is so strained that it’s “egregiously wrong.” So, yes, for noetic peace, if nothing else, the decision should be overturned.

The “Original Intent Originalism” of The Slaughter-House Court

While the first sentence in Professor Wurman’s lead essay addresses itself to the “originalists” on the current Supreme Court, Wurman’s originalism has more in common with the majority’s originalism in The Slaughter-House Cases than it does with the originalism of a majority of the current Court. This difference makes it unlikely that his originalist arguments would move the Court.

As is well known, “originalism” is a label that sweeps within it a multitude of not-necessarily consistent views. One basic divide separates “original intentions originalism” and “original meaning originalism,” also known as “textualism.” Wurman focuses his analysis on who said what about the privileges or immunities clause, as if their intentions or expectations should guide our understanding of the texts.

Contrasting with Wurman’s originalism is textualism, championed most notably by Antonin Scalia. In his 1997 book, A Matter of Interpretation, Scalia expressly dismisses as “waste” the use of legislative history to construe the meaning of legal texts. He wrote, “What I look for in the Constitution is precisely what I look for in a statute: the original meaning of the text, not what the original draftsmen intended.”

Much of Wurman’s analysis may be of historical interest regarding the debates surrounding the 14th Amendment. Yet it is unclear that his “careful examination of the debates over the clause’s scope and work” demonstrates that, at least as currently constituted, “the Supreme Court cannot continue to ignore this clause.” Even the dissenters in Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia, wrapped themselves in the mantle of textualism, arguing only that in its textualism the majority opinion only applied textualism incorrectly. They did not argue that original-meaning originalism—that is, textualism—should not have been applied to construe the legal text.

The irony is that Wurman’s originalism shares more in common with the originalism of the Slaughter-House majority than it shares with the originalist now on the Court. The Court devotes a lengthy section of its opinion to identifying the manifest public purposes of the Civil War Amendments, including the 14th:

The most cursory glance at these articles discloses a unity of purpose, when taken in connection with the history of the times, which cannot fail to have an important bearing on any question of doubt concerning their true meaning. Nor can such doubts, when any reasonably exist, be safely and rationally solved without a reference to that history. . . . Fortunately that history is fresh within the memory of us all, and its leading features, as they bear upon the matter before us, free from doubt.

. . .

We repeat, then, in the light of this recapitulation of events, almost too recent to be called history, but which are familiar to us all; and on the most casual examination of the language of these amendments, no one can fail to be impressed with the one pervading purpose found in them all, lying at the foundation of each, and without which none of them would have been even suggested; we mean the freedom of the slave race, the security and firm establishment of that freedom, and the protection of the newly-made freeman and citizen from the oppressions of those who had formerly exercised unlimited dominion over him

The Court adds that “[w]e do not say that no one else but the negro can share in this protection.” But it signals its skepticism that the privileges or immunities clause sweeps much further than that, as “[b]oth the language and spirit of these articles are to have their fair and just weight in any question of construction.”

To be sure, legislative debates often include debate over the “public meaning” of proposed legal texts. But in applying original-intent originalism, Wurman, for example, would apparently defer even to the concededly “unorthodox reading” of the Article IV, Section 2 privileges and immunities clause found in “statements of John Bingham,” to read an “intrastate” protection into the 14th Amendment’s privileges or immunities clause even without overturning the majority’s narrow limitation of the scope of the 14th Amendment’s clause. Textualists on the Court are not likely to be persuaded by Wurman’s original-intent-originalism arguments.

Wurman conflates two separate legal concepts, concepts which, when separated, would identically apply to a revitalized privileges or immunities clause.

A Rightly Construed Privileges or Immunities Clause Would Not Reverse the Slaughter-House Outcome

There is a puzzle in the structure of the majority opinion in The Slaughter-House Cases. The Court devotes over a fourth of its majority opinion—seven pages—to a discussion of the reasonability of the Louisiana law. All of this is dicta given the second and third parts of the opinion, holding that the privileges or immunities clause does not apply to state actions abridging state privileges or immunities.

But that the Court’s entire discussion is dicta does not mean it is without purpose. The discussion grants the dissents’ criteria for state actions that would still be permitted by the privileges or immunities clause if it applied to state actions of this sort and concludes that the Louisiana action would be constitutionally reasonable.

As with much commentary on The Slaughter-House Cases, Professor Wurman largely ignores the Court’s discussion of the rationale for the Louisiana statute itself, aside from referring to the “ostensible” public-health rationale for the law. But if the law would still be upheld by courts even if the privileges or immunities clause did apply to state actions of this sort, it raises a serious question of whether a revitalized privileges or immunities clause would in fact afford any greater protection to economic liberty, as Wurman suggests it would.

A solution to the puzzle of the dicta in the majority’s opinion is that they’re answering the dissents on the dissents’ own grounds. Justice Bradley is explicit in his dissent that the questions circle around the “reasonability” of the Louisiana regulation:

First. Is it one of the rights and privileges of a citizen of the United States to pursue such civil employment as he may choose to adopt, subject to such reasonable regulations as may be prescribed by law? Secondly. Is a monopoly, or exclusive right, given to one person to the exclusion of all others, to keep slaughterhouses, in a district of nearly twelve hundred square miles, for the supply of meat for a large city, a reasonable regulation of that employment which the legislature has a right to impose? (emphasis added)

Justice Field puts the “reasonability” language in the mouth of a Circuit Court judge in Louisiana, nonetheless also frames the question as one of the reasonability of the Louisiana legislation:

[I]n delivering the opinion of the [Louisiana circuit court, the judge] observed that it might be difficult to enumerate or define what were the essential privileges of a citizen of the United States. . . [but] it might be safely said that “it is one of the privileges of every American citizen to adopt and follow such lawful industrial pursuit, not injurious to the community, as he may see fit, without unreasonable regulation or molestation, and without being restricted by any of those unjust, oppressive, and odious monopolies or exclusive privileges which have been condemned by all free governments.” (emphasis added)

The majority opinion responds to the dissents’ arguments with its extended analysis explaining why the Louisiana regulation is reasonable, notwithstanding its subsequent discussion of why the privileges or immunities clause does not apply in these cases:

The wisdom of the monopoly granted by the legislature may be open to question, but it is difficult to see a justification for the assertion that the butchers are deprived of the right to labor in their occupation, or the people of their daily service in preparing food, or how this statute can be said to destroy the business of the butcher, or seriously interfere with its pursuit.

. . .

It cannot be denied that the statute under consideration is aptly framed to remove from the more densely populated part or the city, the noxious slaughter-houses, and large and offensive collections of animals necessarily incident to the slaughtering business of a large city, and to locate them where the convenience, health, and comfort of the people require they shall be located. And it must be conceded that the means adopted by the act for this purpose are appropriate, are stringent, and effectual.

Despite the state-level statute at issue in this case, the Court cites McCulloch v. Maryland, invoking that case’s construction of the “necessary and proper clause” as a sort of “reasonability” gloss: “wherever a legislature has the right to accomplish a certain result, and that result is best attained by means of a corporation, it has the right to create such a corporation.”

The majority then waves away the dissents’ discussion of the common law’s treatment of monopoly in the dissenting opinions with the comment that “all such references are to monopolies established by the [British] monarch in derogation of the rights of his subjects, or arise out of transactions in which the people were unrepresented, and their interests uncared for.” The majority then expressly affirmed its unqualified opinion that the British Parliament (as opposed to the Crown) has and could unquestionably create legal monopolies, as could the state legislatures in the United States:

[T]he Parliament of Great Britain, representing the people in their legislative functions, and the legislative bodies of this country, have from time immemorial to the present day, continued to grant to persons and corporations exclusive privileges—privileges denied to other citizens—privileges which come within any just definition of the word monopoly, as much as those now under consideration; and that the power to do this has never been questioned or denied. (Emphasis added.)

Merely applying the privileges or immunities clause to the type of state actions at issue in The Slaughter-House Cases would not have changed the Court’s decision to uphold the Louisiana law at issue in the case. This in turn raises doubts that revitalizing the clause would have the impact on protecting economic liberty that Wurman suggests it would.

Privileges or Immunities and Substantive Due Process

Professor Wurman writes that the “implications of overturning Slaughter-House and resurrecting the privileges or immunities clause can hardly be overstated”; that “the clause covers economic liberties like contract and property just as much as any other liberty,” and so, “there is simply no justification for ‘rational’ or ‘any conceivable’ basis scrutiny.“

Wurman, however, conflates two separate legal concepts, concepts which, when separated, would identically apply to a revitalized privileges or immunities clause. The clause’s protection of economic liberties would almost certainly mirror protections the Court provides to economic liberty under the 14th Amendment’s Due Process clause.

First, Wurman conflates the question of whether a right is protected by the Constitution with the question of what standard of review courts apply to evaluate whether the right has been abridged. Economic rights remain protected by the substantive implications of the Due Process clause, it’s just that abridgments of those rights are evaluated by courts under the deferential rational-basis test, rather than higher “intermediate”- or “strict-scrutiny” tests.

For example, in the famous Footnote 4 of Carolene Products, the issue isn’t whether general economic rights are unprotected, but rather what sorts of abridgments would be “subjected to more exacting judicial scrutiny under the general prohibitions of the Fourteenth Amendment than are most other types of legislation.”

Shifting the textual locus of protected economic rights from the 14th Amendment Due Process clause to the 14th Amendment privileges or immunities clause would not perforce change the standard of review courts apply to evaluate abridgments of those rights.

This point does not require the continued use of the rational basis test. After all, in Lochner, the dissenters who would have upheld that New York statute flatly affirmed that the Constitution protects “a liberty of contract which cannot be violated.” The standard of review the dissenters applied—which verbally mirrored the test applied by the majority in Lochner—was,

[I]n determining the question of power to interfere with liberty of contract, the court may inquire whether the means devised by the State are germane to an end which may be lawfully accomplished and have a real or substantial relation to the protection of health.

Rather, the majority and dissenters disagreed on whether or not economic legislation came to it with the presumption of constitutionality. The dissenters said “yes,” the majority implied not, although never expressly said as much. Wurman’s privileges or immunities clause would seemingly place the burden of proof on the state (states would “demonstrate that its regulation is reasonably related to the purpose of the right” (emphasis added)). It is unclear, however, that even an originalist Court would necessarily agree with Wurman and thereby resurrect the distinctive feature of the Lochner-era’s economic substantive due process.

I am all for overturning the textual evisceration of the privileges or immunities clause that occurred in The Slaughter-House Cases. I am even—although this is a closer call given possibly unintended consequences—in favor of some sort of heightened judicial scrutiny of economic legislation beyond the deferential rationality test. I am skeptical, however, that the former would perforce accomplish the latter.