Gratitude for the privileges that American citizenship bestows, and for those who made those privileges and their extension possible is in short supply.

Gratitude, Nationalism, and Memory

One of the better attested findings of psychology is that gratitude is a key to personal contentment and well-being. It tempers feelings of sadness. It reduces any sense of isolation, connecting us to many beyond ourselves, including family members, friends, and teachers—essentially anyone in the wide circle of those who have helped us along.

And the research also tells us how to cultivate gratitude. Tell people that they did important good deeds for you. Write that seventh grade teacher who taught you the elements of good writing. Call a friend to recall together how you helped one another through some nadir of youth. Keep a gratitude journal every day or at least every week, marking down the small kindnesses and gifts of affection from which you have benefited.

This insight can be applied to a nation as whole. A country can become less divided and polarized—indeed happier—if it cultivates a public life where gratitude is front and center. Gratitude for past achievements of individuals and communities create common bonds. And if national gratitude can be part of our social happiness, the absence of a politics of gratitude broadly conceived is a pressing American problem.

Gratitude faces obstacles in a democracy. Electoral politics is future oriented—famously focusing on a question: What have you done for me lately? By contrast, gratitude is necessarily oriented to the past. Partisan politics often takes its energy from cultivating resentments. But gratitude is all about bringing people together. Nevertheless, these obstacles are all the more reason that any democratic nation—indeed any self-governing region or institution—needs a public life that has mechanisms for encouraging gratitude.

Indeed, the idea that we should be grateful for what our nation has done for us in the past is what is best in the revival of nationalism. Some nations—even those that refer to themselves as a fatherland to encourage gratitude by the analogy to family—may have difficulty making that claim credibly, because the misdeeds of their society outweigh its contributions, but that cannot be seriously argued of America. The Declaration of Independence and Constitution remain landmarks of enlightenment thought, inspiring nations around the world to limited, democratic government. More recently the United States saved the world twice from totalitarianism—once by providing the muscle to defeat Nazi Germany and then by providing the dogged long-term strategy and material resources necessary to overcome Soviet communism. And through two centuries, no nation has rivaled ours in innovation not only in science but in business, contributing to huge increases in standards of living both here and around the world.

That record of moral and economic success is arguably the greatest such achievement of any society in human history, and our history should prompt gratitude among our citizens. The new nationalism is in part a response to political movements that complain of various failings of the United States, but do not appear to have any recognition of the sacrifices that had led to the nation’s enormous successes. Americans who have taken a quiet pride in their nation and are not very attentive to the details of politics are nevertheless dismayed by politicians and pundits who now harp on America’s past failures. It makes sense why they are more attracted to nationalism. In contrast, the movements critical of the nation’s past often resemble now-successful children focused entirely on flaws in their elderly parents, all the while ignoring all the help and succor they received for decades as they came to maturity. That lack of proportion seems so astonishing–a species of “monster ingratitude.”

Of course, Americans ought to recognize their nation’s failings as well, especially the original sin of slavery. But even here too, the fight against slavery was rooted in original principles of freedom and equality laid out in its founding documents, and the Civil War claimed hundreds of thousands of lives, the sacrifice of which pales in comparison to our present disagreements.

Identity politics—the even worse successor to the political correctness of the 1990s—is problematic in no small part because it lacks gratitude for the achievement of the past, whatever the failings of the present. Of course, people in the past acted imperfectly when considered from the perspective of the present. But the greatest of those in the past whom we honor did so many things right often under difficult circumstances that we live far better lives than if they had not lived. That is the relevant question when it comes to gratitude, and it is not a surprise that it is the central question of our most enduring holiday movie, It’s a Wonderful Life. The whole town gets together to express its gratefulness to George Bailey who, despite his mistakes, has contributed greatly—especially when we compare the situation to a world where he was not born.

If we would become a happier nation by being a more grateful nation, we need changes in public life that would call forth more gratitude. The first is a greater public focus on American history. Gratitude to the nation depends on knowledge of the past. Unfortunately, as David Davenport and Gordon Lloyd have shown, K-12 history has become a casualty of the culture wars. Students are not getting the basic facts that would allow them even to differentiate the good and bad in our nation’s history. Without both, they cannot even begin to feel gratitude for those who have come before.

But even beyond improving the teaching of history, public life could be better embrace opportunities for gratitude. Many of our holidays that should inspire gratitude, such as Memorial Day, Labor Day, Presidents’ Day, and Martin Luther King Day, have been moved from the day on which they actually fall to the nearest Monday. As a result, they have simply become more times for vacation or shopping than times for remembrance. We should consider moving at least some of them back to their actual dates. That would focus attention more on what they stand for.

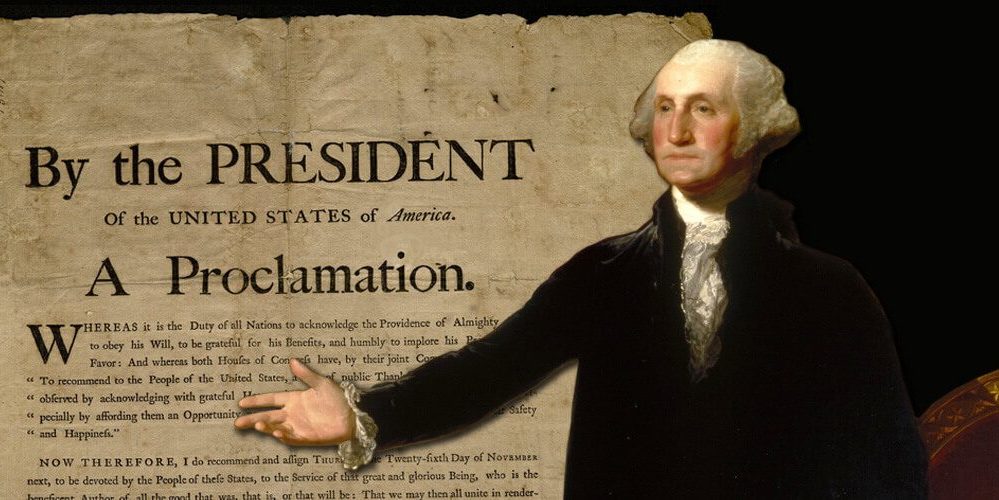

There is precedent for such a return to memory. Veterans Day was celebrated on the closest Monday until a public outcry during the Ford Administration forced it to be moved back. And while we are it, we should change the name of Presidents’ Day back to George Washington’s Birthday. President’s Day is too generic to concentrate the mind on much of anything. Our first President’s birthday would permit us to draw our attention to Washington’s achievements in the Revolutionary War and in the Early Republic, and his indispensable character as President.

Gratitude for the past also contains important moral and political lessons for the present. With Washington, for instance, the message is clear: prudence, careful deliberation, and, above all, the reality that character counts. We should welcome more opportunities to contemplate them.

Happy Thanksgiving!