Horror movies compel us to accept what we do not want to believe in.

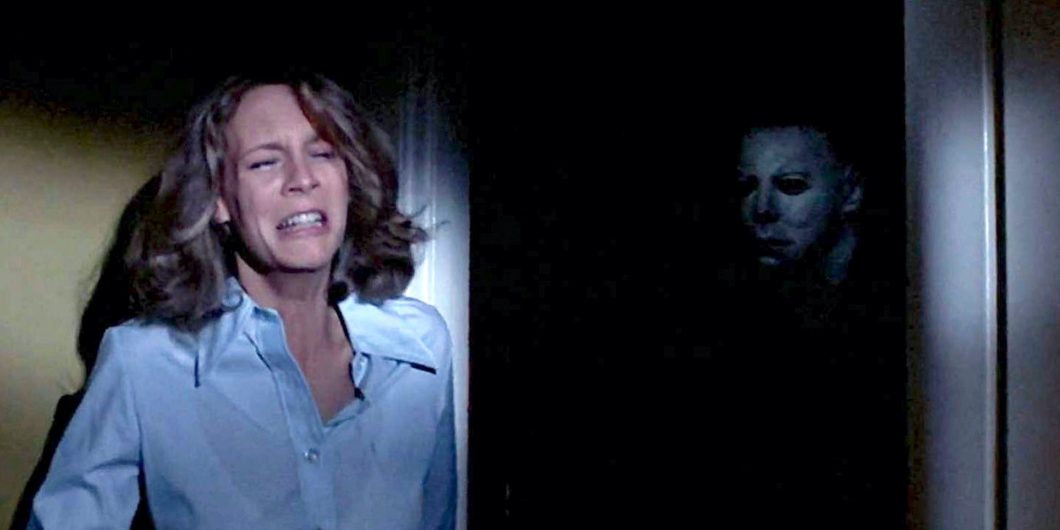

Halloween and the Confrontation with Evil

John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) introduced one of the most famous images of evil in our pop culture, Michael Meyers, a child murderer who returns as an implacable adult suburban America must face. Unfortunately, as the movie turned into a franchise and the American imagination seized on the knife-wielding masked murderer, the point of Halloween was completely lost. But the confrontation between evil and clueless youth, abandoned by adults, is timely, so I offer some reflections.

Halloween is a story about suburban America, where teenagers leave high school not knowing what to do with their lives—and worse, clueless about life’s purposes. Our freedom and love of change confuse our kids, who see the future as a black wall. Halloween shows the liberation of sex, drugs, and parties as the democratic consequence of this cluelessness; but we also hear about teenagers stealing headstones and some minor larceny. The only student who knows what she wants and is working for it is the protagonist (Jaime Lee Curtis), who survives the ordeal.

Meanwhile, we hear from the adults that there is no evil in Haddonfield, a perfect suburban development where precise geometry meets domestic tranquility. When evil did come, fifteen years before the events of the film, in the body of a boy who murdered his sister, he was banished to an asylum. But modern liberalism’s highest power, therapy employing the police power of the state, fails to fix or even contain evil. Middle-class America must then face it without institutional protection.

The Imagination of Evil

Carpenter knows Americans share an unconfessed fascination with evil—from house to house, from TV to TV, the same horror movies play during Halloween. But of course, we find ourselves transfixed by an evil neutered by scare quotes. Carpenter dramatizes this cultural problem: Disbelieving in nature, middle-class adults could not imagine a truly evil child. Placing their faith in the beneficence of the sanitized suburbs, then they leave their own kids to face grownup evil alone.

Horror fans have long joked that sexual promiscuity is punished with death in slasher movies. But Carpenter wanted to show, instead, that when adults become fanatics of respectability, they deny there is any darkness in their or their children’s hearts. As a result, the children become irresponsible. They find suburban comfort stifling, boring, and think of escape. They turn to fantasy, surrendering to their desires rather than learning what to do with their lives.

Still, it’s not obvious why Carpenter should punish teenaged cluelessness with death. This especially baffles critics who dislike the intense moralism of horror—visiting wrath on apparently innocent or witless protagonists and their communities. Why not blame the parents who think they have conquered evil, or at least banished it? After all, by proving unable to face it or to protect their children, do they not seem all the more deserving? Ordinary life can lead people blindly into hubris and thus catastrophe.

In America, however, the young have to take responsibility for themselves. Carpenter therefore adopts the outlook of the young, who are given to extremes of cowardice and recklessness. Foolish, arrogant, overprotective adults have failed to prepare kids, including our protagonist, for the real world, which includes evil. But Carpenter’s real attack on Progressive piety goes beyond social criticism, into psychology. He suggests facing evil is necessary to becoming an adult. That’s what our heroine does. She learns she cannot rely on her stoner friends or absentee adults. Instead, she becomes a strong woman by becoming a mother and saving her children’s lives.

Carpenter shows his seriousness about evil by demonstrating how Halloween is a joke in America. We laugh at images of evil and make them sexy. Hollywood-style capitalism blind people to evil, so Carpenter makes evil real by bringing horror to our homes, instead of exotic locales. Old horror movies don’t scare people—so Carpenter tries anew to remind people: We either learn to live with knowledge of evil, or we will always recur to the mental asylum where we play Dr. Jekyll and create Mr. Hyde. More therapy, more monsters.

Manliness and Greatness

Halloween was an attempt to warn America that we’d be creating new evil if we tried to achieve too much order, too much peaceful prosperity, indeed, utopia. Children would end up irresponsible and defenseless in face of life’s difficulties, since they had never been prepared by hardship. They’d be whining or doing escapist things to protest their helplessness. And some would turn murderer. You can see them on the news if you don’t believe Carpenter.

Horror is moralistic storytelling, defying our imperatives to have a happy end. Instead, those protagonists survive who face evil, become manly, protective of the innocent, and are ready to use violence.

Carpenter’s most shocking idea is something like teaching kids about guns. He has Jamie Lee Curtis imitate the murderer’s technique for breaking and entering and then his knife technique, too. She has to overcome her fear first and then let her anger guide her—she learns from evil how to defeat it. This strange lesson is especially unwelcome to liberals who want to banish violence from the world, though they might applaud it on occasion. But it is the core of American conservatism that tells us to take care of ourselves, to be responsible, to deal with fear well, and which has more contempt for hysteria than for conflict.

Horror is moralistic storytelling, defying our imperatives to have a happy end or make liberals happy by sending a message about the evils of prejudice. Instead, those protagonists survive who face evil, become manly, protective of the innocent, and are ready to use violence. Carpenter made Halloween as an alternative education for young Americans, taking seriously their experience, starting with their confusion and their desire to escape the control of adults who seem deluded because they, too, are children.

Other directors also saw the problem of a suburbia charmed by Hollywood and reacted with horror. Think of Wes Craven’s Nightmare on Elm St. (1984), another story about teenagers wasting their lives in fantasies, faced with evil they cannot comprehend, and ignored by adults too respectable to take the experience of children seriously. But the culture fixated on cool images, franchise money, and made jokes of murderers like Freddy Kruger. Instead of confronting our fears, we got in the habit of laughing at them because, after all, horror, too, is just images on a screen, easily parodied.

Carpenter, Craven, and others like them instead gave us ordinary heroines that would fit in our ordinary lives—smart young women who study hard, become grownups, and try to make a future for themselves. This is very decent, if sentimental, but it doesn’t fit horror and it’s no accident that they’re not memorable—they’re too much like us, they lack greatness. Evil at least is impressive and reminds us of the holy—if only by crime.

Happy Halloween!