Ike's Mystique

At the height of the Iran Contra scandal in Washington, “Saturday Night Live” had a funny skit about Ronald Reagan. It showed the President’s folksy, out-to-lunch personality to be a façade. Behind closed doors, he was a worker bee, driving younger staff members to exhaustion. Liberals could only entertain such a possibility fictionally. To them, Reagan was a lazy leader, “sleepwalking through history.”

Liberal avoidance of such a possibility tracked back to Dwight David Eisenhower’s 1953-1961 administration. To the liberals of that era, he was a disconnected President, more interested in his golf game than in leading the nation. Worse, he lacked political courage, specifically with regard to halting a rampaging Joe McCarthy.

The conservatives, too, thought he lacked backbone—specifically, in his refusal to aid the Hungarian resistance fighters when they were being crushed by Soviet troops in 1956. Such inaction caused William F. Buckley and National Review to support a more conservative candidate (California Republican Senator William Knowland) over President Eisenhower when he sought reelection that year.

The reality, though, was closer to the SNL version. Ike’s golf game was a façade, a Cold War strategy to assure a jittery America that all was well. Meanwhile, Eisenhower was an energetic leader behind the scenes. His advertised policy for halting Soviet imperialism was to use nuclear weapons. In actuality he favored covert action, a less risky means of preventing any dominoes’ falling on his watch. For example, he authorized a joint U.S. and British intelligence plan to overthrow the authoritarian and destabilizing Prime Minister of Iran, Mohammad Mossadegh, without loss of American life or blowback (more on this later). The following year, he greenlit a coup against a pro-Soviet ruler, Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala.

The noted British historian Paul Johnson is not fooled as were conservatives and liberals in the 1950s. But this doesn’t make him original. The absence of footnotes and a bibliography from Eisenhower: A Life should put the reader on alert. He seeks to rehabilitate Ike into a much more intelligent and involved President. He is not breaking new territory, however, but riding a 30-year-old wave begun, ironically, by Arthur Schlesinger, a Democrat and a Camelot merchant if there ever was one. In 1983, reading newly declassified documents, Schlesinger revised his opinion of Eisenhower as a lazy dope. Instead he found him to be an energetic and effective leader. Liberal journalist Murray Kempton recanted as well, now regarding the President as highly intelligent.

Johnson, a Tory admirer of Thatcher and Reagan, is so busy rebutting ghostly historians and pundits that he misses some of the more interesting aspects of the man, especially as against one of his successor Republican Presidents. Eisenhower’s reputation as a liberal Republican then would not make him one today. Instead, he was the ancestor of Ronald Reagan. Both were big issue leaders. Upon entering office, Eisenhower listed his priorities on paper, two of which, cutting taxes and a strong national defense, would also be Reagan’s.

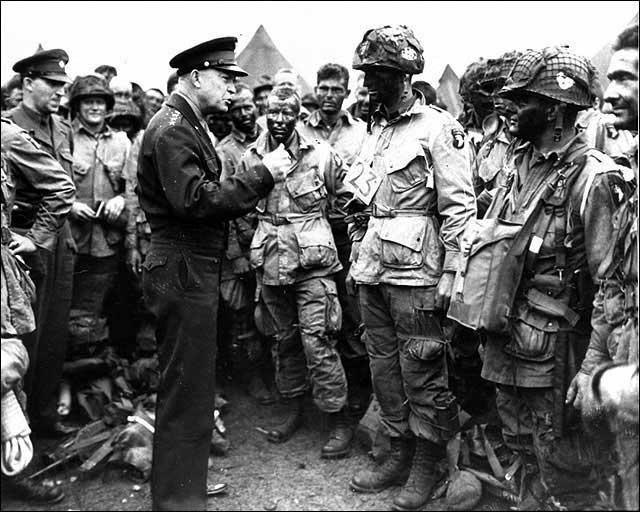

Moreover, the biographer’s refusal to transcend 1950s-era arguments and debates causes him to overlook how Eisenhower’s military background informed his policies. A popular perception that soldiers are bloodthirsty, eager to empty the silos, belies the reality that many of them are loath to start a war. Ike epitomized this stance. Having witnessed—in fact having waged, as Supreme Allied Commander against the Nazis—total war, with its accompanying body counts, he was determined not to risk American lives in a much more lethal nuclear exchange.

Johnson does note that, unlike Presidents Truman and Kennedy, “On six separate occasions during his eight years in office, he decisively dismissed advice that they be deployed”—but he doesn’t see how this restraint was linked to Ike’s military background. Generals, which Kennedy and Truman were not (the former was a Navy boat captain in World War II, and the latter an artillery officer in World War I), see the big picture of carnage. To Johnson’s credit, he does travel forward to the JFK and LBJ administrations to note that Eisenhower knew the folly of fighting a land war in Asia, and hence did not put troops into Vietnam.

This determination to avoid massive war deaths naturally led him toward covert action, with its relatively low body count and plausible deniability. Here too, though, Johnson is not up to speed. His neglect of new scholarship and debate leads him to hew to the CIA’s 60-year-old, self-serving accounts. As Ray Takeyh has shown in recent writings in Foreign Affairs and elsewhere, the CIA was timid during the 1953 ousting of Mossadegh. It was the Iranian army—disgusted with the intransigence of a Prime Minister who, in pushing the country’s monarchy aside, nationalized Iran’s oil industry and brought on a British blockade—that really toppled Mossadegh. The army was backed not only by the shah’s supporters but by the country’s intellectuals, and also its mullahs, in doing so. Ike never went public with this supposed Anglo-American success, but the CIA did, and had Johnson reviewed this matter thoroughly he might have viewed the Agency’s version with a historian’s skepticism.

This is billed as a “succinct biography.” In fact, its 144 pages moved Publisher’s Weekly to use the phrase “bizarrely brief.” While an excellent primer on a rehabilitated Eisenhower, the book is lively but superficial.