Trump is trying to faithfully execute his office and, in his own way, to strengthen the Constitution.

Imbalanced by Checks

Is democracy about politics or policy? Or, by some felicitous logic, do they end up coinciding? “Popularism” is the idea, currently urged by some on the center-left, that doing what the electorate says it wants is a winning electoral strategy and, at the same time, a perfectly good way of making sound policy in service of the national good.

Donald Trump’s popularist innovations are a neglected aspect of his vast and varied political oeuvre. One such innovation, which seemed anomalous and almost self-parodying when announced, is shaping up to have an enduring influence on American politics.

The path-breaking episode took place in the wake of the passage of the CARES Act at the end of March 2020. Overwhelming bipartisan majorities in both chambers of Congress had just passed the largest emergency spending package in the nation’s history, exceeding $2 trillion. About $300 billion of that money would be used to cut checks to American adults in the amount of $1,200. Rather than awaiting that year’s tax filing, this dispersal of funds was to take place as soon as possible. Eligible Americans (individuals with incomes of $99,000 or less, and corresponding levels for other types of filers) whose bank accounts were already known to the federal government through income tax refunds would receive the money as a direct deposit into their checking account. Others, especially lower-income Americans, would receive paper checks. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) managed to effect these transfers beginning in mid-April.

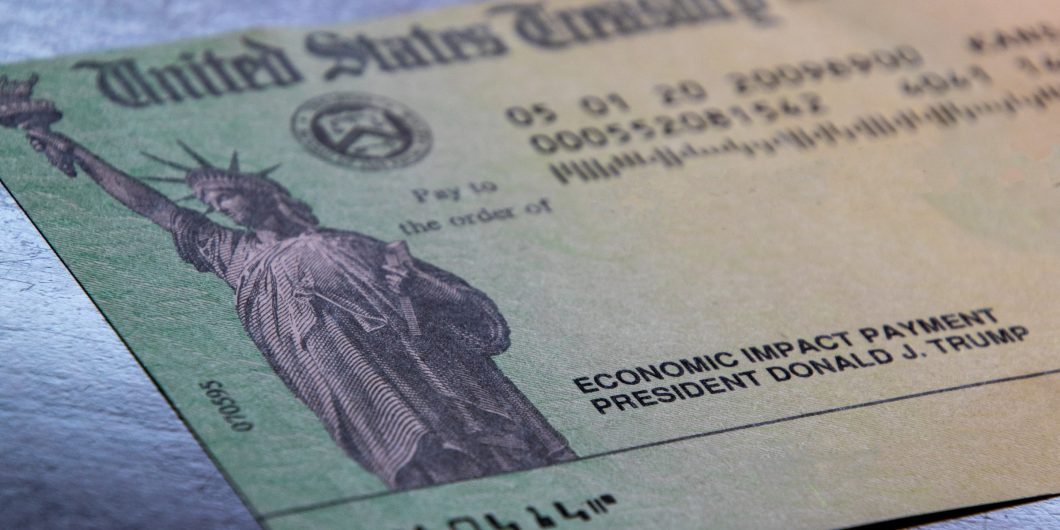

But along the way to getting this money out the door, the IRS did something never before seen in American history: on the memo line of the checks, they printed “Economic Impact Payment,” and directly below that, “President Donald J. Trump.” As reported by ABC News, this addition came late in the process of mocking up the checks to be sent out, and IRS officials repeatedly insisted on receiving confirmation that this was really something that the Secretary of the Treasury wanted. Yes, indeed, the Treasury Secretary wanted these checks to be branded, as no payments in American history ever had been before. (Generally, such payments bear only the signature of the disbursing officer of the payment center, without identifying any political figure.)

Both President Trump and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin would later claim that this idea was Mnuchin’s, but its Trumpian flair is unmistakable. While denying that he was responsible for the move, on April 15 the president would also say, “I’m sure people will be very happy to get a big, fat, beautiful check and my name is on it.”

The branding exercise itself resulted in predictable jokes about Trump steaks, Trump vodka, and the like. But, undoubtedly, people were happy to get the checks. People like getting money. And it is far from crazy for a politician to try to take credit for getting it to them.

Determined not to make this a one-off event, in late September 2020, Trump surprised his administration by promising to send out $8 billion worth of drug-discount cards to American seniors. These cards would come pre-loaded with $200 to spend on prescription drugs of any kind. Their target delivery date: late October. Judd Deere, a White House spokesperson, told Politico: “This has nothing to do with politics. It’s good policy and demonstrates the president is continuing to deliver on his promises to our nation’s seniors.” Congress could not have shared credit for these cards, for they would have had nothing at all to do with them. Trump was acting on his own, using “demonstration project” authority that Congress had given to try new things in healthcare delivery, apparently not entirely without legal basis. In the end, following another theme of the administration, the drug card plan failed to come off before the election. Indeed, officials were still hustling to get the cards out in the final lame-duck days of Trump’s presidency, but they once again ran out of time.

What did happen was another round of right-away checks sent out as a part of the giant omnibus spending and COVID relief bill passed in December 2020. A furious debate about the size of these checks ensued, with Democrats pushing for $2,000 and Republicans insisting on stopping at $600. President Trump sided, unexpectedly, with Democrats, thereby creating an awkward situation for the two Georgia senators then in run-off elections for their seats. Both David Perdue and Kelly Loeffler quickly joined the chorus in favor of bigger checks. In response, the House of Representatives passed a bill, 275-134, to raise the amount: the Caring for Americans with Supplemental Help Act. CASH! The Republican-controlled Senate rejected the effort, the checks remained $600, Trump leveled some bitter recriminations, and Perdue and Loeffler lost their races.

Lessons were learned by popularists of all political stripes. But with control of the House, Senate, and White House, Democrats have been the ones in a position to put them into practice.

First, in the opening days of the Biden administration, Democrats emphasized that they would be making good on the $2,000 promise of the last president. Their American Rescue Plan, passed in February 2021, followed through with $1,400 checks. They did not bear Joe Biden’s name on their memo line, but the administration did send out letters to all payment recipients that heralded the law that was responsible for them, including noting that “There may be other parts of the American Rescue Plan that will help you as well.” Democrats collectively spared no effort in making it clear who Americans could thank for this largesse—though, to be fair, a few progressives did grouse about the final amount, as they felt a full $2,000 that took no notice of the $600 sent out by the December legislation would have better fulfilled the people’s true desires.

At least with old-fashioned vote-buying, everyone understood that something corrupt was happening. . . . The most enthusiastic popularists today convince themselves that they are pure as the driven snow.

That was only the beginning. In that same American Rescue Plan, Democrats enacted a major expansion of the child tax credit, making it bigger and fully refundable. This has been hailed as a major policy victory that will (if made permanent, as Democrats are now seeking to do in their Build Back Better legislation) nearly end child poverty in America. But it has also been structured to be paid out on a monthly basis, such that every month parents have a reminder that Democrats are the party that delivers for them. Biden described this feature as “life-changing.” In preparation for the first payments in July 2021, the administration declared June 21 “Child Tax Credit Awareness Day.”

Democrats also wish to incorporate features reminiscent of Trump’s drug-card plan in their big spending bill. Concerned that new policies like dental coverage through Medicare would not take effect fast enough if worked through normal bureaucratic channels, they hope to get $1,000 vouchers sent out to seniors before the midterm election.

Senator Ron Wyden of Oregon puts it this way: “I think Democrats feel very strongly that it’s important to move now so, in particular, we have results to show the American people a year from now in the late summer or early fall of 2022.” That’s a very polite way of saying that naked vote-buying has now become a normalized feature of American politics. In fine popularist fashion, proponents of these plans will, of course, insist that they are only trying to enact good policies that help Americans, and especially low-income ones. Is it their fault if these great policies are also their ticket to reelection?

This is a very worrying trend—a kind of logical endpoint of demagogy that our Founding Fathers worried about, but which has been mercifully absent from most of American political history. In his (lone) inaugural address in 1797, John Adams warned that, however pleased the citizens of the young Republic were with its early performance,

we should be unfaithful to ourselves if we should ever lose sight of the danger to our liberties if anything partial or extraneous should infect the purity of our free, fair, virtuous, and independent elections. If an election is to be determined by a majority of a single vote, and that can be procured by a party through artifice or corruption, the Government may be the choice of a party for its own ends, not of the nation for the national good.

Adams inhabited a different political world, in which politicians did not deign to campaign openly for election lest they seem too ambitious. But anyone who wants our politics to be something other than a clientelist competition for dollars should heed these wise words. Pandering to large groups through open transfers seems less corrupt than old-fashioned vote-buying; the proponents of these transfers assure us that these popular policies are out there for all to see, with nobody being manipulated. But the attention to the timing of checks and the brazen scramble to up the dollar amounts, without so much as an argument explaining why blanket distributions are the best policy, give away the game. (If the name of the CASH Act didn’t already.) At least with old-fashioned vote-buying, everyone understood that something corrupt was happening. Those participating in that corruption presumably believed the system needed a little subversion here and there to function fairly. The most enthusiastic popularists today convince themselves that they are pure as the driven snow. To the extent their strategy is not paying the dividends they expected, they feel genuinely aggrieved.

Once politically-strategized cash payments are normalized, it becomes a real pain to be the one to stand up and say: Hey, here’s an idea, instead of sending people money for no particular reason (if generalized economic stress seemed plausible in March 2020, it was much less so in December 2020 or February 2021), how about we don’t send them money, and let people’s own economic decisions decide where the money flows? Time was that Americans believed in that as a baseline, and the politicians proposing to turn things upside-down had to make an extraordinary case. If the presumption has flipped, then we may be about to find out just how much our government can become “the choice of a party for its own ends.”