Is Big Government Here to Stay?

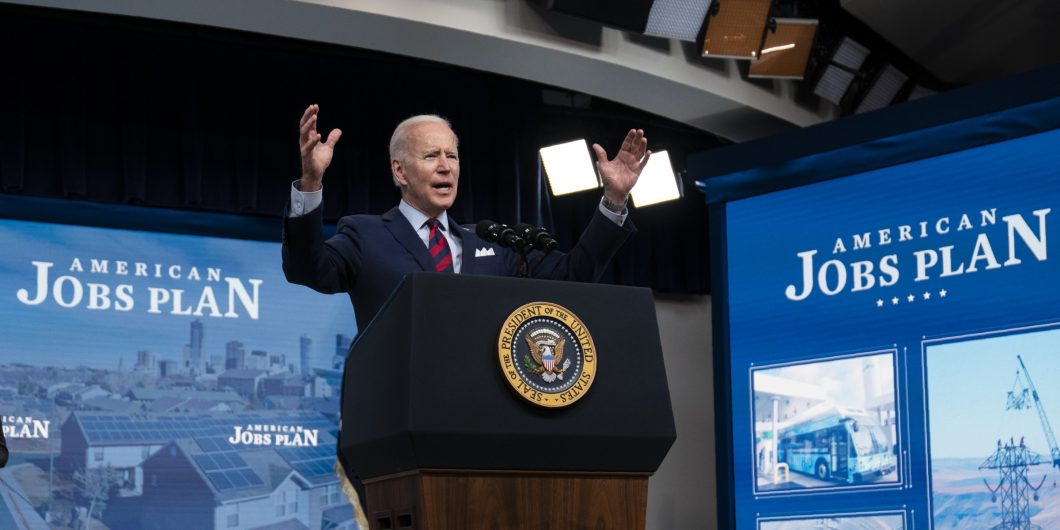

The Democrats of 2021 are determined not to let the COVID crisis go to waste. Instead, they want the extraordinary government spending that marked the past year to become America’s new normal. President Biden has proposed: 1) increasing discretionary spending by $1.5 trillion next year, 16% more than the current level; 2) spending an additional $2.3 trillion on infrastructure—very broadly defined—over the next eight years; and 3) an additional $1.8 trillion in federal spending and tax credits over the next ten years for a variety of social welfare purposes.

A trillion here, a trillion there. The question is not how soon we’re talking real money. In the belief that if something can’t go on forever, it won’t, the economic question is how soon before we’re talking real consequences: higher taxes, inflation, and interest rates, leading to stagnation and, ultimately, an America that is “a kinder, gentler place of permanent decline,” in the words of New York Times columnist Bret Stephens.

Debt’s Steady March

We first need to address the political question about the correlation of forces—popular demands, underlying sentiments, resonant ideas—that determine fiscal policy. The coronavirus pandemic did not bring about a new political reality. Rather, it continued and fortified the polity’s established disposition. Prior to the past decade, total federal debt stood just short of $10 trillion, 68% of the Gross Domestic Product. That baseline was more than twice the 32% level of 1981, the lowest debt-to-GDP ratio since 1940. By 2019, after a recovery that was initially sluggish but then became robust, the debt had grown to $22.7 trillion, a sum equal to 107% of GDP. It marked the eighth straight year in which the federal debt was greater than GDP. Previously, the most recent breach of the 100% red line had been from 1945 to 1947, when a much smaller, less affluent country borrowed heavily to secure victory in World War II.

Over the past 13 years, the American people tried every political configuration made possible by our Constitution and two-party system. We had a Republican president, George W. Bush, and a Democratic Congress after the 2006 midterm elections. 2008 brought a Democratic president, Barack Obama, and a Democratic Congress. The elections of 2010 yielded a Democratic president and a divided Congress, with a Democratic Senate and Republican House of Representatives. In 2014, two years after reelecting the Democratic president, the voters chose a Republican House and Senate. That alignment gave way, in 2016, to a Republican Congress and a Republican president, Donald Trump. In 2018, however, the voters once more endorsed a divided government and Congress with a Republican Senate and Democratic House.

Then, in 2020’s first weeks, the coronavirus pandemic began. In response, Congress enacted laws over the ensuing year to stabilize and stimulate the economy, the first of which spent $2.2 trillion and the second a miserly $900 billion. By the time of the third, which will spend $1.9 trillion, the voters had cycled back to a Democratic president and a (narrowly) Democratic Congress. This total of $5 trillion in new federal spending, none of it offset by any new or increased taxes, exceeded the $4.5 trillion of total federal outlays in 2019, the fiscal year that ended less than six months before anyone had heard of COVID.

Irrespective, then, of which party was running things or how power was shared among the elected branches, the one constant was that federal spending and borrowing increased relentlessly. There is no way to reflect on this record and discern an inchoate electoral majority that will demand or even tolerate fiscal restraint. Absent a robust constituency favoring government contraction, democratic fundamentals guarantee that government will expand.

This tells us, in the first place, that the Tea Party movement, which emerged spontaneously in 2009, turned out to be a Tea Party moment. Its populist energies were catalyzed by federal bailouts, stimulus spending, and the proposal for what came to be known as Obamacare. The Tea Party objections against ramping up government redistribution were, in part, moral: Journalist Rick Santelli ignited the uprising by asking on CNBC, “How many of you people want to pay for your neighbor’s mortgage who has an extra bathroom and can’t pay their bills?”

The motives were also fiscal. The raisons d’etre of Congressman Paul Ryan’s various “roadmaps” were the beliefs that: 1) federal spending could not exceed, permanently and increasingly, federal tax revenues; and 2) that federal spending could not be controlled without curtailing entitlement programs, Social Security and Medicare in particular. In 2019 those two behemoths distributed $1.7 trillion, 38% of all federal outlays. Interest on the national debt, $375 billion, represented another 8% of federal spending. Self-government becomes a tenuous proposition in a republic where nearly half of public expenditures are effectively beyond the reach of elected legislators.

A welfare state limited to what can be financed by soaking the rich or borrowing is one that will never approximate the comprehensive benefits packages offered in western Europe.

This is why the Tea Party’s motives were also constitutional. From Gadsden flags to the study of America’s founding, the Tea Party evinced a concern for reconsidering the proper scope of government. Which matters should be handled by the federal government, which by the states, and which ones were best left to private citizens acting without government funds or regulations? In asking such questions, the Tea Party repatriated the exiled ideas that the federal government had neither the ability nor the authority to solve every problem, and that some “problems” were dissatisfactions inherent in the human condition.

Within the decade, however, conservative populism shifted its focus from Big Government to nationalism and political correctness. We’ll need more time, perspective, and information to say how much of this change Donald Trump caused and how much he merely discerned. In any case, the Trumpist brief that the Deep State was corrupt and unaccountable differs from the Reaganite contention that Big Government is illegitimate and unsustainable. The futility of the Tea Party movement became clear when, after six years of Republican denunciations of Obamacare, a Republican president and Congress could neither summon the courage to repeal it nor devise an alternative to replace it. Whatever the Tea Party’s abstract thoughts about the proper limits of government, conservative populists turned out to have nothing more than mild objections to the welfare state, as such, but a strong aversion to conferring its benefits on the undeserving, such as slackers and illegal immigrants.

The Great Progressive Experiment

For all that, Democratic celebrations about a “big government revival” and “fundamental reorientation of the role of government” are premature. It remains to be seen how much of President Biden’s spending proposals can be passed in a Congress where the Republican minority is completely opposed and the slender Democratic majority is not unanimously in favor. Democrats’ apprehensions rest on the well-grounded fear that the 2022 elections will find voters rebuking rather than endorsing the Biden agenda, returning congressional Democrats to the minority as a result.

The votes to be cast by Congress and the country during the Biden era will cause Democrats to be apprehensive for two reasons. First, popular skepticism about government is based on doubts that government programs can actually alleviate the problems they purport to solve. Doing things is not the same as accomplishing things. Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society gave way to Republican victories in five of the next six presidential elections for several reasons, one of the biggest being that the extravagant talk and spending about Model Cities and Head Starts yielded few clear improvements and much demonstrable harm. Thus, Obama administration advisor Steven Rattner worries that if the Biden Democrats botch the implementation of the new initiatives they enact, then voters who cannot find “actual real results” will revert to seeing government as “the enemy again.” Increasing the budget and scope of government programs does not guarantee beneficial outcomes if, as Yale law professor Peter Schuck has argued, “federal domestic policy failures are caused by deep, recurrent, and endemic structural conditions.”

The second reason to doubt that the public is ready to demand or even accept a dramatic increase in the scope of government is the dog that doesn’t bark—the argument for more government that Democrats no longer make. Joe Biden was completing his second term in the U.S. Senate when Democrat Walter Mondale promised the American people in 1984 that he would raise their taxes if elected president . . . and then went on to lose 49 states to Ronald Reagan. Biden was one of many Democratic politicians scarred by the experience. Like every Democratic presidential nominee of the 21st century, he ran on a promise to confine any federal tax increases to the most affluent Americans. In Biden’s case, the cutoff point was $400,000 of household income, which exempts 95% of the country from any tax increase.

The implication for Democrats is as clear as it is ominous: voters are amenable to the Democrats’ domestic agenda, but only if someone else pays for it. That someone else could be a rich person or a big corporation. In the case of deficit financing, the someone else is a future taxpayer, who will pay for today’s outlays plus the accrued interest. When even the political party explicitly in favor of activist government takes this position, America winds up with one of the lowest levels of taxation among developed countries, barely half as much as the European social democracies that Democrats want to emulate. But a welfare state limited to what can be financed by soaking the rich or borrowing is one that will never approximate the comprehensive benefits packages offered in western Europe.

What no Democrat has been willing to argue for 37 years is that the party’s proposals are so beneficial that the typical American will be better off because of them, even taking into account the higher taxes that finance the programs. Democratic politicians and activists certainly believe that their proposals possess those virtues. It’s just that they cannot see a way to talk enough voters out of their skepticism to make a platform like Walter Mondale’s electorally viable.

That problem, in turn, is not rhetorical but governmental, which takes us back to the problem of implementation. If some of the Biden proposals are enacted and go on to be smashing successes at enhancing the national quality of life, these achievements might create enough political space for Democrats to raise the subject of government programs that require higher taxes on most people, not just a small, wealthy minority. But the prospect of that high reward carries with it a high risk: if the Biden programs do not succeed in ways that vindicate the idea of expanding government, the failure will, in Steven Rattner’s words, “set back the cause of progressivism for several more decades.”