While technology can help facilitate action, self-government requires dedication to an ongoing activity in which Americans make decisions together.

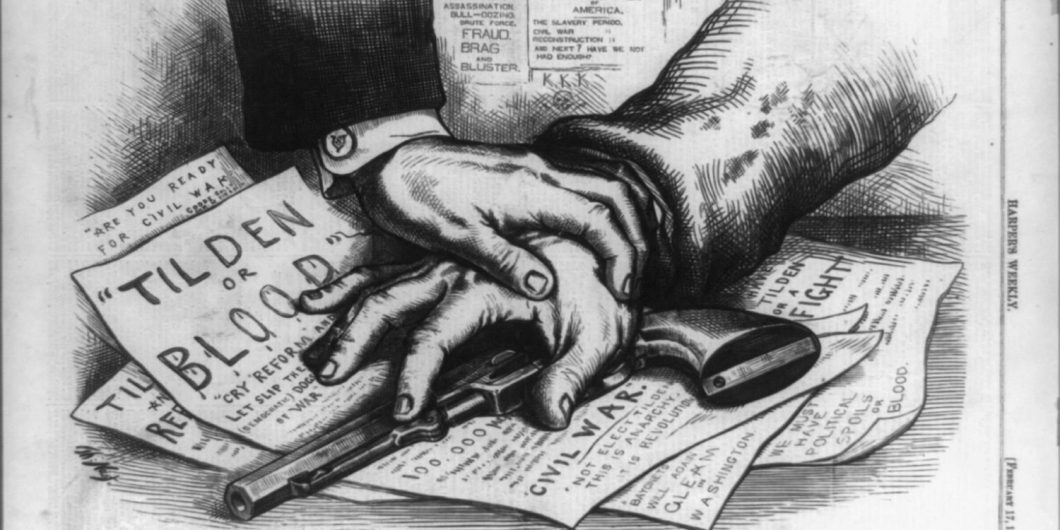

Is the Spirit of (18)76 Alive?

Historian Roy Morris Jr. called the election of 1876 “the last battle of the Civil War.” Could the election of 2020 sound the trumpet for another charge?

Serious people are writing serious books and articles about the possibility of secession. In 1876, most Americans had personal experience with secession, coloring how they viewed the kind of talk that arose during and after the election. No one alive today has had such an experience, so secession talk is bandied about with less respect for the potential consequences.

Election night is supposed to be the end of the process. In 2020 as in 1876, the voting will end but the counting will just be getting started, and nobody knows how long it will take to finish. What happens in the days and weeks that follow will determine whether the Trump-Biden contest was, as politicians endlessly predict, the most important election of our lifetime.

Then as now, the country was evenly divided politically. There was frequent turnover in party control of Congress. People were all too willing to commit violence to achieve their political ends.

Perhaps the similarity most visible to voters will be that the candidate leading on election night is not necessarily going to be the one ultimately declared the winner.

That’s where the problems started in 1876, and where the danger lurks in 2020.

“Annual, autumnal outbreaks in the South“

In 1876, the Civil War had been over for only 11 years. The wounds were so raw that several Southern states refused to participate in the centennial celebration that opened in May in Philadelphia.

The country was also still in a touchy economic position, suffering from the lingering effects of the economic depression that grew out of the Panic of 1873.

Hanging over the entire process was the Southern question.

Andrew Johnson had declared in 1866 that “peace, order, tranquility, and civil authority” reigned in the South. But it wasn’t true, and to the extent order did prevail, it was not the order that congressional Republicans wanted to see.

Freedmen were being denied their civil rights. Violence was rampant. In defiance of Johnson, Republicans enacted the Reconstruction Act of 1867, which disenfranchised thousands of former Confederates, expanded military occupation of Southern states, and barred readmission to any state that failed to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment. These steps were intended to punish rebels, protect the lives and property of freed blacks, and—not incidentally—ensure that black Republican men could vote while ex-Confederate, white Democrats could not.

But violence and intimidation persisted and many in the North began to grow weary of the Southern problem. “The whole public are tired out with these annual, autumnal outbreaks in the South,” President Ulysses S. Grant said in the wake of the 1874 midterm elections, which went badly for his party.

By 1876, only the governments of Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina had not been “redeemed” by Democrats.

It all added up to an inescapable conclusion: Reconstruction was doomed no matter who was elected president. Republicans were weary from the fight and Democrats had opposed the enterprise from the beginning.

There were genuine fears among Union veterans and other Northern patriots about turning the government back over to the Democrats who, only the decade before, had rent it asunder. Ohio Senator John Sherman, brother of Civil War hero William Tecumseh Sherman, spoke for them when he declared that “election of a Democratic president means a restoration to full power in the government of the worst elements of the rebel Democracy.” Waving the bloody shirt still worked.

The self-interested desire of those in office to cling to power should never be discounted. Republicans had held the reins for 16 years; patronage jobs depended on it; livelihoods were at stake. For many, that outweighed any policy concern.

Democrats were just as eager to get back into power after so long an absence as Republicans were to hold on. That didn’t mean their concerns about a Grant administration awash in corruption were not genuine.

But however real the concerns were about the rights of Southern blacks or corruption in the White House, the significance of the election of 1876 and its aftermath did not rest on policy outcomes. What put the country at risk was the careless indifference to constitutional process.

“Corruptions, failures, and disappointments“

Democratic nominee Samuel Tilden won the popular vote by more than 250,000 votes over Republican Rutherford B. Hayes in an election in which 82 percent of eligible voters cast a ballot, the highest turnout ever.

On election night, it also appeared Tilden had a victory in the Electoral College. But the outcome was disputed in three states: Florida, with four electoral votes; Louisiana with eight; and South Carolina with seven. One electoral vote in Oregon would also be challenged.

The election hinged on the outcome in those three unreconstructed states. Tilden led narrowly in two, Hayes in one. The apparatus of power in all three remained in the hands of Republicans.

1876 is an example of what can happen when political opponents are portrayed not simply as wrong, but as evil. To stop evil, anything is permissible.

“In the contest for the electoral votes of these states, all that slithered through the corruption, failures, and disappointments of American politics during the previous decade rose to the surface,” historian Richard White wrote.

In each of the contested states, the process was marked by violence, intimidation, and abuse of power.

A divided Congress was stalemated. Republicans wanted the president of the Senate to determine which of the multiple electors’ votes submitted by various officials in the disputed states were valid, count them, and declare Hayes the winner. Democrats wanted the House to declare that neither candidate had an electoral vote majority, leaving the House to decide the winner, which would have been Tilden.

Instead, lawmakers created an electoral commission, against the wishes of both Hayes and Tilden. The commission comprised five members from each chamber, evenly divided between the parties, four Supreme Court justices evenly divided between the parties, and a fifth justice chosen by the other four. That was expected to be David Davis of Illinois, an independent who hadn’t even voted in the 1876 election. But Davis was elected to the Senate, so Associate Justice Joseph Bradley, a Republican, was selected.

On party line votes, the commission endorsed the state vote totals certified by Republican election officials and voted 8-7 to award the disputed electoral votes to Hayes.

When it became clear to congressional Democrats that every decision was going to fall Hayes’ way, they used procedural methods to stall a final vote count. But Southern Democrats struck a deal with Republicans—they would oppose delay in return for a commitment to withdraw remaining federal troops from the South. They also got a promise to appoint a Southern Democrat to the cabinet (Senator David M. Key of Tennessee would be named postmaster general, a prime patronage position).

Deals were part of the fabric of politics. Because Reconstruction was on its last legs anyway, this deal was less than met the eye.

But even less-than-meets-the-eye deals can backfire, and in Hayes’ case, the result was predictable. He became “His Fraudulency.” Half the country considered his presidency illegitimate. There was much talk, mostly in the North, of raising an army and marching on Washington. In the end, the talk came to nothing. “We have just emerged from one civil war,” Tilden said. “It will never do to engage in another.”

Civil war was avoided but cries of “fraud of the century”—the title Morris chose for his one-sided book—have echoed down the years. Historian Michael Holt took another view. “Had blacks been allowed to vote freely, Hayes easily would have carried all three states in dispute, Mississippi, and perhaps Alabama as well,” he wrote in the best book about the election of 1876. Without that “force, intimidation, and fraud,” the sorry circus that followed would never have been necessary.

“The republic will live“

While some today are voicing loud concerns about voter fraud, today’s problems are more likely to arise from confusion and incompetence. With tens of millions of people voting by mail for the first time in a system not designed to handle that kind of load, delays and disputes are certain as results change and victories are converted into defeats.

Though the possibility of outright fraud shouldn’t be dismissed, the 21st century can’t hold a candle on that score to the 19th, when fraud was practiced widely and well by all sides. An army of lawyers deployed southward in 1877 couldn’t prevent it. An even larger legal army will likely be on the march this week.

The most damning aspect of the 1876 election, though, was the ad hoc electoral commission, an extra-constitutional creation that “functioned as a quasi-judicial body,” in the words of historian Sidney J. Pomerantz.

Disappointed Democrats called the Supreme Court’s decision that settled the 2000 election “unprecedented.” But in 1876, virtually all parties insisted that the Court play a role in settling the dispute. “What bothered them most,” Holt wrote, “was the idea that Congress itself, without any explicit constitutional authorization, should attempt to do so.”

We are not likely to see such a commission this time around. The courts, not a congressionally appointed commission, will settle any outstanding questions related to the 2020 election, lending a legitimate finality to the outcome for most Americans. As we’ve just gotten through one fight about the future of the Supreme Court, dissatisfied partisans can be counted on to add fuel to the fire by questioning the legitimacy of any decision they don’t like.

One can always take historical comparisons too far. The stakes are different and the issues unique in this election. But 1876 is an example of what can happen when political opponents are portrayed not simply as wrong, but as evil. To stop evil, anything is permissible. And partisan media were eager to sew the wind.

Those dynamics exist today, compounded by the excessive demands and expectations we place on government. The bitterness is so deep because the stakes are so high. One of the motivations of 19th-century civil service reform was to lower the stakes by curtailing the spoils system. While a permanent bureaucracy has its own problems, a mad scramble to fill government clerkships every four or eight years is not among them. One of the motivations of modern conservatism is to make elections less important by lessening the role government plays in our lives. The trend has been running the other way for almost 100 years, which helps explain the all-consuming nature of politics in today’s culture.

To preserve hope, partisans need to remember that no loss in American politics is final.

No matter who wins this year, an election in 2022 will give voters an opportunity to rein in whatever excesses they feel have been perpetrated by the winners of 2020. It happened in 2006, 2010, 2014, and 2018. There is no reason to believe it can’t happen again. And in 2024 there’s another presidential election. There will always be another election.

The danger comes not from an election loss, but from believing that the fear of losing justifies any action to prevent a loss or even violence in response to a loss. More than a third of respondents in a recent survey said violence is justified when their side loses. That’s how we ended up in a civil war to begin with.

“The republic will live,” Tilden said in the summer of 1877. “The institutions of our fathers are not to expire in shame.” But, as in 1876-77, there is talk of violence. If the leaders of either party, their followers, or the media repeat in 2020-21 the mistakes of 1876-77, focusing on short-term advantage at the expense of preserving constitutional norms and respect for core principles, there is no guarantee that Tilden’s confident prediction will come to pass.

May the losers of the 2020 election, whoever they are and whenever they are determined, follow his example.