These are views that I now hold because Roger Scruton had been my teacher.

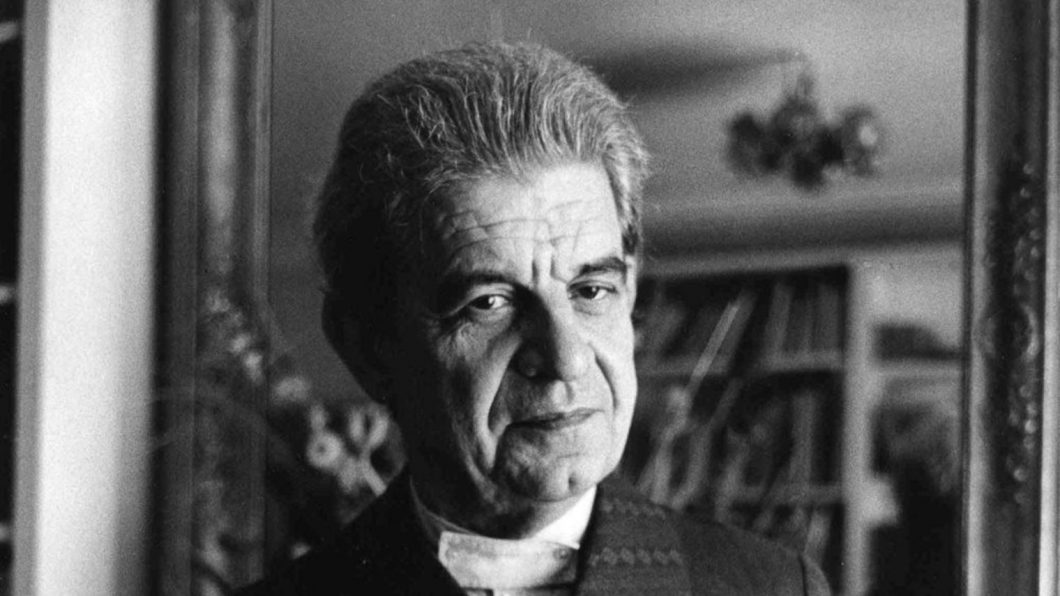

Jacques Lacan: Conservative Icon?

In literary and philosophical circles there is an assumption that Jacques Lacan is a leftist. The French psychoanalyst, who died in 1981 aged 80, certainly is a darling of the Left, but is he a leftist? What he definitely is not is a Progressive because he tells us again and again that psychoanalysis is not a progressive doctrine. Lacan holds himself to be the most accurate interpreter of Freud, and the most astute developer of his legacy. About the politics of psychoanalysis, he says:

Freud was a humanitarian… But, on the other hand, he wasn’t a simpleton, so that one can say as well, and we have the texts to prove it, that he was no progressive. I am sorry but it’s a fact, Freud was in no way a progressive. And as far as this is concerned, there are even some extraordinarily scandalous things in his writings (J. Lacan, Seminar 7).

Part of the problem is that Lacan’s writings are forbidding, to say the least, and assessments of his work tend to be done on the back of his principal commentators, who are leftists. An example of this phenomenon is a long piece by Roger Scruton. Scruton, who is no stranger to these pages (here and here), is a sophisticated reader but in a treatment of Slavoj Žižek, where he unmasked Žižek’s excuses for Stalin and Mao, he lumps Lacan in with Žižek as a communist fellow-traveler. It is understandable: Žižek is Lacan’s most well known commentator and a prolific leftist writer.

Scruton believes that Žižek’s revolutionary fervor is aided and abetted by Lacan’s theory of the Other. Scruton writes:

The mirror stage provides the infant with an illusory (and brief) idea of the self, as an all-powerful other in the world of others. But this self is soon to be crushed by the big Other, a character based on the good-breast/bad-breast, good-cop/bad-cop scenario invented by psychoanalyst Melanie Klein. In the course of expounding the tragic aftermath of this encounter, Lacan comes up with astounding aperçus, often repeated without explanation by his disciples, as though they have changed the course of intellectual history.

This passage does not get Lacan quite right. More immediate than the difficulty in understanding what Lacan is going on about is to notice that even Scruton is discussing a Lacan situated in the commentarial tradition. This is a shame because “the big Other” is a conservative phenomenon. In more familiar language “big Other” is built up from the offices and institutions of establishment whilst the discrete concrete persons you and I know and interact with, even if they happen to hold high office as the boss, the college president, or U.S. senator, are others alongside our own selves.

For Lacan, the basic problem psychoanalysis addresses is identity. Identity is fraught, inescapably mixed up with affirmation and aggression, the desire for social recognition. A simple example of this is queuing: why we do it, what we think about the person who jumps the queue, and what we think he must think of you and I if he thinks we’ll put up with it. The tussle for social recognition in the phenomenon of queuing is part and parcel of a struggle for recognition that goes on inside our own psyches. Our subjective lives are themselves a complex social struggle. Indeed, the two are intimately united. Our innermost lives are also social and public: my personal sense of self inextricably linked to public, established, hierarchical structures of recognition. This insight is the heart of Adam Smith’s theory of the spectator and the establishment credentials of “big Other” is familiar to all of us who read and love Edmund Burke.

Animating the whole psychological, social, and political order is what Lacan calls the Thing. An interpretation of Freud’s idea of the death instinct, it is a place we want to experience yet shudder before. The Thing is the origin of civilization. Civilization lets us dip our toes in the Thing, to get the thrill of it, and even a savage thrill, yet civilization holds us back, as well (this idea of a subterfuge thrill is perhaps Lacan’s most famous and what he calls jouissance).

Kierkegaard toys with this idea in his existentialist treatment of Abraham and Isaac. In his 1843 classic Fear and Trembling, Kierkegaard aims to shake the Christian community from its bourgeois slumbers insisting the story is about the anguish and horror of God holding Abraham on the edge of being a child murderer. For Lacan, our culture returns again and again to this story because it gives us a glimpse of the Thing, full exposure to which we avoid. I recently heard tell of a theologian who this Thanksgiving at the carving of the turkey snagged the newborn of a young visiting couple, who just so happened to be called Isaac, and laughingly re-enacted the Abraham story on the festive table. This is the sort of crazed joking incident that does not surprise Lacan.

Glimpses of the Thing are found in holes, a vase, for example, or containers, like matchboxes, or in gaps, like the wounds of Christ or Isaac’s body missing its head. The psyche hovers about gaps, cultural production constantly circling around holes: hence the centrality of funeral rites the world over, managing the void of grief; sometimes these rites literally center on going down into a sepulcher.

Lacan’s “Other” is a ridge built around the Thing, somewhat like a hill fort, to block access. The ridge is what Lacan calls the symbolic, the vast array of words, manners, institutions, and rites that compose civilization. Out of our myriad individual interactions with civilization, parts of this array leave a vapor trail back to the Thing, and the purpose of the analyst is to identify those trails to help the patient (the analysand in Lacan’s lexicon) modify his or her relationship to the Thing. Just as philosophy is the practice of the art of dying, according to Socrates, so for Lacan psychoanalysis is about the management of our identity in relationship to aggression and death.

Pace Scruton, the self is not crushed by the Other but generated by it, individuated and given identity by its generative knots of manners and law. It makes us civilized. The Other places us in history, in receipt of an inheritance (Burke) of a patchwork of values (Shaftesbury) participated in, and monitored by, our neighbors (Hume and Smith). With a nod and a wink it also lets us indulge our dark conflicted longing to engage with the Thing (think here opera, ballet, and most classical theatre, never mind the slasher flicks of Hollywood, characters like James Bond and Hannibal Lecter, or the never ending appetite for detective fiction).

If the typical watchwords of a progressive are romanticism, imagination, absolute freedom, utility, innovation, and human beneficence—utopia—then Lacan’s watchwords are law, obedience, order, community, manners, art, and fault—tightly controlled aggression. Not all rightists will be happy. Shaftesbury, Smith, and Burke would see much in Lacan to approve. Christian conservatives would recognize in the Thing something akin to the idea of original sin but, and here Scruton is absolutely right, they would baulk at the tragic: Christian thought is tied to a metaphysics of peace, a belief that all began in peace and, despite fault, final reconciliation will happen. Lacan does not agree: tragedy is basic. Surely troubled by the denial of individualism, libertarians might read the tragic as scarcity and find a confirmation of the need for property: the ineliminability of the Thing an explanation for why property will always require inequality and why it stokes the aggressive self-assertion and vanity of capitalism.

My proposition: It is time for rightists to start exploring Lacan and use him to theoretically advance conservatism.