Sebastian Junger's Tribe offers a provocative but flawed argument about manhood today.

James Bond at 70

Seventy years ago, in 1953, Ian Fleming, a British WWII planner and supervisor for commandos, published a brief espionage novel, Casino Royale, and thus James Bond was born. The book allowed Fleming to reimagine British imperial greatness and continue in fiction his command over manly men willing and able to kill and die for a cause, for the thrill of the fight, and for pride. He could speak for civilized society’s necessary assassins.

By the use of his imagination, Fleming became far more successful and important than he had ever been in public service. He ended up orchestrating one of Britain’s most successful cultural exports. Bond was in the mid-20th century what Harry Potter has been in the 21st century. But instead of a bespectacled nerd, ideal for the world wrought by selective colleges and Silicon Valley, audiences fell in love with a cold-blooded killer who seemed able and eager to refuse all the compromises the rest of us feel we have to make.

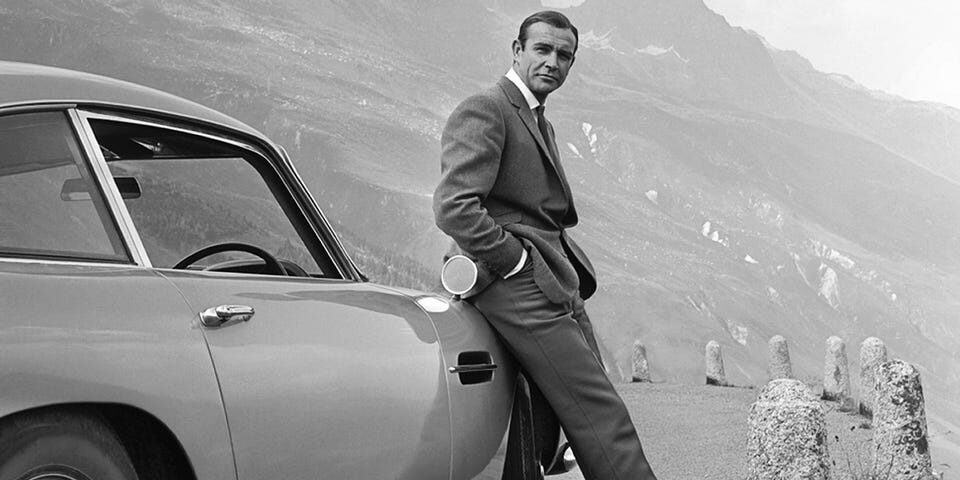

This image of manliness became more popular still, extending as far as mass-media could reach, nine years later, in 1962, when Dr. No appeared, starring Sean Connery as James Bond. All told, Fleming published twelve novels and two short-story collections, with another two novels published posthumously; these gave rise to 26 movies over the last 60 years; and these in turn led to countless imitations and new Bond stories penned by other writers, forever advertising the man of mystery, who combines love of beauty with a curiosity about the ugliest deeds imaginable.

Bond as Hero of the Empire

The novel-film combination also made for an unusual kind of stardom, leading four actors to fame: Connery, Roger Moore, Pierce Brosnan, and Daniel Craig, while maintaining the Bond glamour and spreading throughout the world, for generations, an ideal of manliness. I can’t think of anything that quite compares with it, because it’s still recognizable worldwide as British class presumption freed from its moral restraints or the silly eccentricities and melancholy bred by a stifling class system. Liberated, Bond is the sublime perfume of imperialism, the more popular the more people decry colonialism. As was once said of the British Empire, with its wars and diplomacy, so with Bond and espionage: The sun never sets on his adventures.

Bond, however, did not define martial prowess like the working class action heroes of the 80s and he was not a gym bro like the atomized middleclass men of our time. Connery had been a Mr. Universe bodybuilding contestant, but he’s worlds away from Arnold—his distinguished manners are supposed to conceal his power. Instead of brutality, he defined elegance for men, from the sharp suits to the frivolous witticisms, and especially his success with women.

After all, the great ideological struggle post-WWII was not against communism abroad, but at home against feminism. Men loved Bond because they knew they were losing. Indeed, feminism has won and Bond is now an exemplar of toxic masculinity, probably in need of therapy. Bond was a man’s man and this is not something our elites accept in pop culture—accordingly, the franchise has finally killed him in No Time to Die, a funny title for the pandemic years.

According to the pieties of our times, Bond is now beginning to face censorship for being, as was said of Byron, “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.” The novels are being reprinted for the 70th anniversary of Casino Royale, but now without unkind references to black people.

Perhaps the sensitivity readers—the bleeding consciences of our corporate PR—think other races less important; perhaps it’s an unfolding process of civil rights for fictional characters. Meanwhile, women must still feel the shock of Fleming’s decadent Romanticism, infamous for phrases like “the sweet tang of rape.” Intersectionality is hierarchical, after all, and it’s not yet fully structured in our entertainment.

Sophistication and Daring

For my part, I’m confident Bond will be severely censored and I expect the change to come with the next series of films, when we will have a politically correct 007. Perhaps his mission will be to execute the politically incorrect. He will be a good “ally,” no doubt. Nowadays, this is what passes for a sophisticated view of art—didacticism, it used to be called, and it was despised as moralistic. Works of art used to be judged by how they reveal human nature, not simply by advancing an ideology.

So this may be our last public occasion to think about Bond’s strange success. To some extent, he resembles us. As Kingsley Amis put it in the James Bond Dossier, a volume I highly recommend to fans, Fleming grounded his fantasies in the realities of our commercial society with very realistic notes about products, among other things. Mostly, these were Fleming’s own tastes, and fiction has given him a remarkable influence over the new and prospering mid-century middle-class society. Sophisticated consumerism, one might call it, which may be an ideal in our society—the command to enjoy luxury.

The best image we have of it is James Bond, because he’s part of our modern world, but he is aware of its dark side, too—espionage, not just elections.

Bond went around the world to exotic locations for their beauty and mystery, before tourism became a bourgeois bohemian habit: Experiencing various cultures with consumerist humility. A virtual travel agent with millions of grateful clients! However, Bond was bold and demanding, especially in his vices, drinking and smoking only the best, and chasing after glamorous women. This may come as an insult to career women. Or they may indulge the fantasy of glamour themselves.

As for our own social media FantasyLand, not even the era of Instagram models and influencers has managed to create anything like Bond—perhaps art really is more impressive than life and the fans were right to prefer fiction to fact. Maybe the problem is the softness of our times. Consider Fleming’s description of Bond’s nature in Casino Royale: “Then he slept, and with the warmth and humour of his eyes extinguished, his features relapsed into a taciturn mask, ironical, brutal, and cold.” Who would talk that way today? It would be a PR nightmare.

This begins to show us why Bond is so interesting to men. Fleming knew, in a way none of our writers know today, that at the origin of all modern things we find the greatest man of mystery, brutal and comic, elegant and wise, Machiavelli. Fleming’s description of Bond’s mind in Casino Royale is taken straight out of The Prince, chapter 25: “Bond saw luck as a woman, to be softly wooed or brutally ravaged, never pandered to or pursued.” Bond tries to master fortune—this makes him attractive and also intolerable to the moralistic.

Gambling, admittedly, has lost its decadent aristocratic charm. It has been relegated to an addiction and taken under therapeutic control. We only gamble in the stock markets, where it’s not personal. But we still need Bond’s Machiavellian sangfroid and daring, because the entire economy turns out to be as capricious as Machiavelli said fortune was, however computerized and rationalist our economic and financial systems. We need Bond precisely because he’s bold where we’re cautious, and we know it.

On the other hand, like Bond, we’re all food critics nowadays. We are not satisfied with anything modest, we want the excellent or at least the extreme of variety, what used to be called exotic or ethnic food before that became politically incorrect—call it “food imperialism.” But Bond wasn’t afraid to state his opinions—we tend to hide behind screens when we give bad reviews. He didn’t look for bargains or good things on the cheap, he was proudly disdainful of price—after all, he paid with gambling winnings or the riches of his defeated enemies. All these pleasures came with his dangerous daring, his knowledge that he would die sooner rather than later, which required full concentration on his mission and his circumstances, on the present, rather than planning for a distant, if prosperous retirement. Precisely because we do not live like Bond, we need to understand the difference—we might appreciate the ways in which Bond’s pleasures and agony reveal our way of life in miniature, and what we need to defend it.

Toxic masculinity is manliness when we’re afraid of it and also think we don’t know what to do with it. The best image we have of it is James Bond, because he’s part of our modern world, but he is aware of its dark side, too—espionage, not just elections. We need him to let us know how to think about danger and why we need to face danger to become men. Even women might need Bond to learn how to judge men, but that’s a story for another time.