Judicial Statesmanship versus Judicial Fidelity

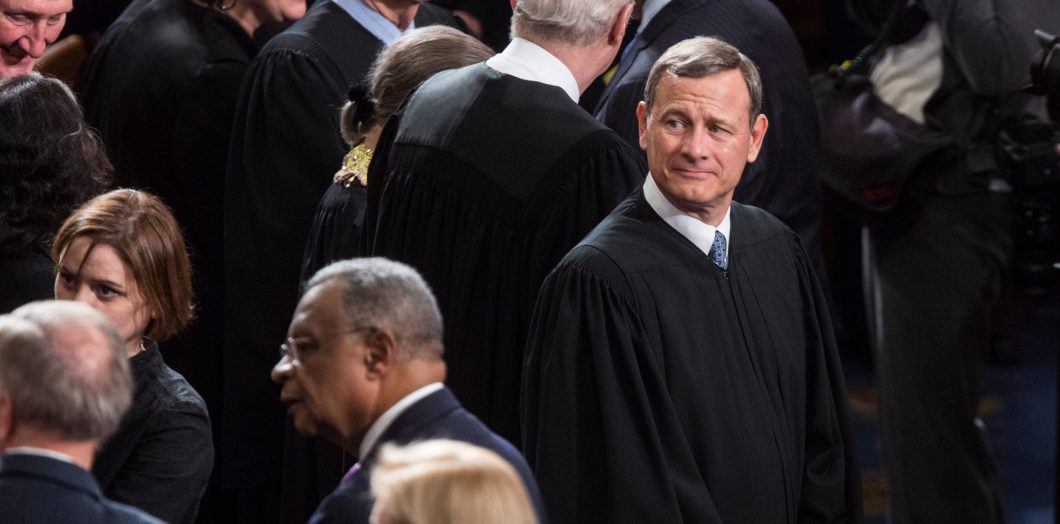

It is commonly thought that Chief Justice John Roberts is very concerned about preserving the legitimacy of the Court in a polarized America. Many believe that as a result, he will become the Court’s balance, making sure it does not lurch too far right, which would supposedly dissipate its political capital.

But a justice’s focus on the political capital of the Court would seem in some tension with a commitment to the rule of law. Under a classic view of justice, the legitimacy of a Court of law does not depend on whether its decisions are perceived as leaning right or leaning left to the appropriate degree. Indeed, since the boundaries of left and right are always changing, a court focused on retaining its political capital would have all the constancy of a weather vane.

Instead, under this classic view, the Court’s legitimacy is rooted in its fidelity to law. The Chief Justice himself has endorsed this conception when he analogized the judicial function to that of an umpire. An umpire does not apportion his calls so that each side gets a sufficient number in its favor. Instead, he calls pitches as he sees them—in legal terms, he seeks to issue the truest and best interpretations of the law in every case.

One way to resolve this tension is to argue that the public cannot be expected to understand the intricacies of legal decisions. Thus, an appearance of neutrality is more important than actual fidelity to gain the public’s diffuse support for the Court and that support in turn is necessary to maintain the rule of law. Without it, the Court may suffer the defiance of government officials. Or even more likely in our day, the legislature may decide to pack the Court with new judges likely to rule more to their liking. That action would truly undermine the rule of law as it would create incentives for each political party to change the composition of the Court when they control the government. Under this view, a Supreme Court justice must necessarily be a judicial statesman sensitive to politics, not just an umpire, if the rule of law is to be maintained for the long term.

But if this resolution were ever satisfactory, it is is less likely to be so in our transparent age, when even the internal deliberations of the Court become public. A new biography of the Chief Justice by Joan Biskupic supports the widespread claim that he changed his mind after the initial vote in NFIB v. Sebelius, the case about the constitutionality of Obamacare. More problematically, it suggests that he “negotiated a compromise decision” with Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan to get their votes to strike down the effective requirement that state expand Medicare while he upheld the mandate to buy insurance on the basis of the taxing power. According to the book, he apparently formed that alliance after failing to find a compromise with Justice Anthony Kennedy, who was put off by Roberts’ efforts.

I do not know how much of this account is accurate, but, if it is true, it does not comport with Roberts’ declared self-conception of the judge as umpire. A judge should follow his duty to declare what the law is rather than seek compromises with his colleagues to burnish the Court’s reputation. In any event, this kind of incident underscores the problem with the idea of judge as a political statesman in the modern era of relative deliberative transparency. The efforts to create an appearance of balance will inevitably become public and at least in some quarters will itself detract from the very political capital that judicial statesmanship seeks to preserve.