Larry Tribe's (Belated) Mea Culpa

Seeing the star of Vice President Biden finally begin to fade with his decision to not seek the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination reminded me of the rather sad spectacle that occurred during his chairmanship of the Senate Judiciary Committee in 1987. When my friend, the late Bernard H. Siegan, was nominated by President Reagan for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit that February, he faced a firestorm of opposition due to his seminal advocacy of property rights and economic liberties.

Siegan’s path-breaking book, Economic Liberties and the Constitution (1980), advocated greater judicial review of legislation affecting property rights and economic liberties than the standard used by the U.S. Supreme Court since West Coast Hotel v. Parrish (1937). For this and other heresies, Siegan was regarded by the legal establishment as a radical—and in some ways he was—but mainly he was ahead of his time.

Later scholars, such as Richard Epstein, Randy Barnett, and David Bernstein, have carried on the debate, and brought grudging academic acceptance—if not consensus—to the point of view that judicial deference to economic regulation may be unwarranted or at least excessive. But, like the first soldier to disembark from the landing craft on Omaha Beach at Normandy, Siegan attracted the most fire.

In any event, Siegan’s critics “borked” him even before President Reagan nominated Robert Bork for the Supreme Court in July 1987. The New York Times described Siegan’s nomination as “one of the most bitterly disputed judicial nominations of the Reagan Era.” “Crank,” “eccentric,” and “out of the mainstream” were just some of the epithets hurled at Siegan.

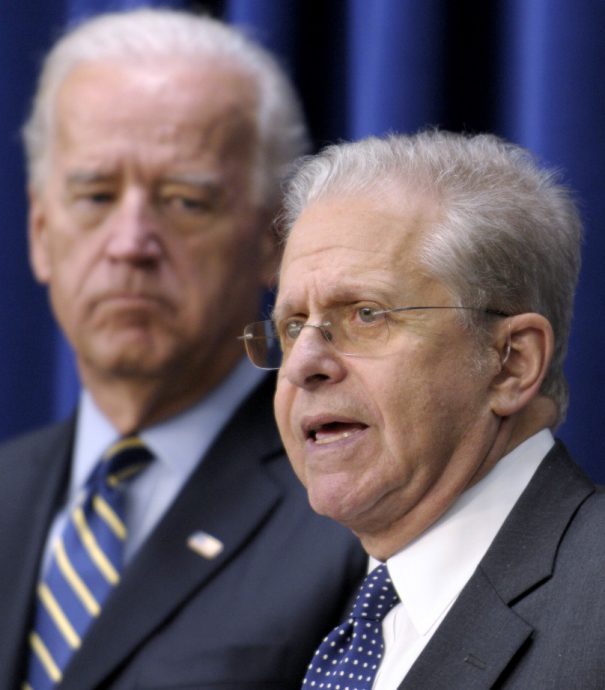

The worst insult, however, came from the esteemed Harvard Law School Professor Laurence H. Tribe, who wrote a letter to the Senate Judiciary Committee intemperately questioning Siegan’s “competence as a constitutional lawyer and his sincerity as a scholar,” and arrogantly deeming Siegan “unfit to serve as a federal judge.” The committee, chaired by Senator Biden (D-DE), dragged out Siegan’s nomination for nearly 18 months—one of the longest delays in U.S. history up to that time—before ultimately rejecting him by an 8 to 6 party-line vote on July 14, 1988. Of the 340 judicial nominations made by President Reagan until then, Siegan’s was only the second to be defeated in committee.

But Tribe’s unseemly grudge against Siegan continued. Tribe gratuitously disparaged Siegan’s scholarship in a footnote to the 1988 second edition of his once-dominant (but now defunct) treatise, American Constitutional Law. Siegan, an incredibly kind and gentle soul, was wounded by Tribe’s remarks, and wrote Tribe a letter in 1991 objecting to them and asking him to reconsider. In a long response to Siegan (provided to me by Bernie’s devoted widow, Shelley Siegan), Tribe did something remarkable: he said he had reconsidered. He now agreed with Siegan on the doctrinal point at issue, and would make an appropriate revision to the forthcoming supplement to his treatise.

Alas, the supplement was never published, having been eclipsed by a two-volume third edition. The first of the volumes was issued in 2000, but the second—where he intended to revisit his doctrinal quarrel with Siegan—went by the wayside with Tribe’s abandonment of the entire treatise. Unfortunately, Siegan died on March 27, 2006, never living to see his name “cleared” by Laurence Tribe.

While sorting through her late husband’s files, Shelley Siegan discovered the correspondence between Bernie and Tribe, and in 2006 she wrote Tribe a letter, following up to see if the disputed matters had ever been resolved, and also asking whether Tribe would reconsider his harsh assessment of Bernie in his letter to Joe Biden 19 years earlier. Once again, Tribe wrote a long and gracious response, explaining why the intended “retraction” in his treatise had not occurred, and also apologizing for his poisonous letter to Biden during Siegan’s nomination fight (which he claimed not to have re-read in the intervening 19 years).

Tribe admitted to her that if Bernie’s nomination were pending today, and if he (Tribe) were asked to weigh in, he would not have made what he conceded was an “unnecessarily ad hominem” statement questioning Bernie’s legal competence or scholarly sincerity. “To help correct the record if only posthumously,” Tribe copied Biden on his response to Shelley Siegan.

Shelley was understandably gratified by Tribe’s generous response, and after re-reading Tribe’s letter “many times,” she wrote him back to beseech him to ask Biden to have the letter reprinted in the Congressional Record, in order to clear Bernie’s reputation and restore some much-needed civility to the confirmation process. Tribe indicated that he would try to get Biden to do so, but stated that “I’m not sure he will agree.”

Predictably, Biden never came through. Ultimately, in August 2007, more than 20 years after Tribe publicly defamed Siegan, Bernie’s dear friend, Representative Dana Rohrabacher (R-CA), inserted Tribe’s long-overdue apology in the Congressional Record.

The moral of this story? There are several: The judicial confirmation process can be brutal and unprincipled; the academic mainstream, like the channel of a river, moves over time; intellectual leadership often bears a steep personal cost; this intellectual leader, Bernie Siegan, was a good and decent man; Larry Tribe incorrectly assumed omniscience but eventually realized his error and apologized; late apologies are better than none at all; and Shelley Siegan is a loving and devoted widow who worked to clear her late husband’s reputation even after his death. We should all be so lucky. Bernie, we miss you.