We are in a period of political polarization unprecedented since at least the New Deal, and its waves have engulfed our fundamental document.

Laurence Tribe Gets the VP's Vote Wrong

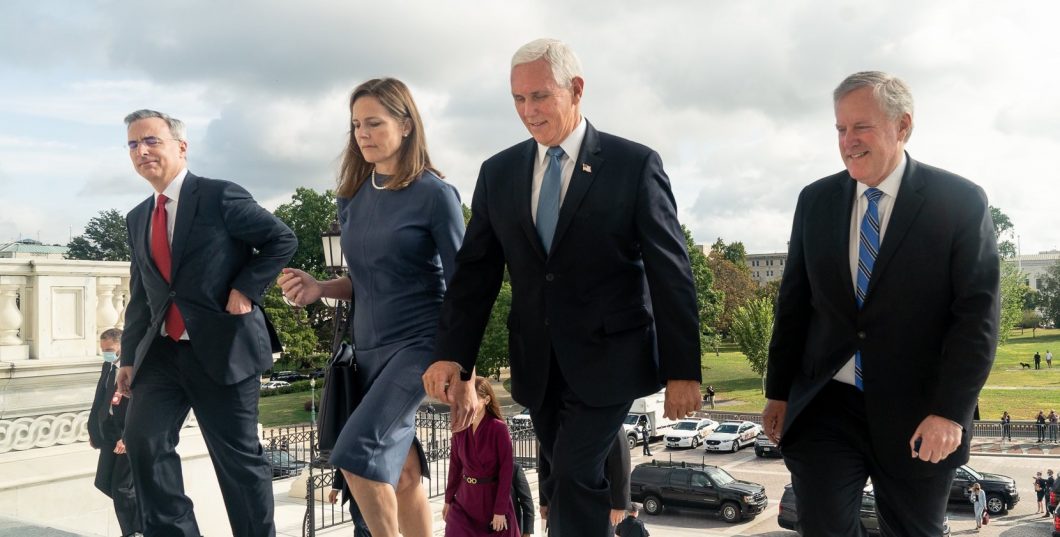

Those opposed to putting Amy Barrett on the Supreme Court are making legal arguments to thwart her confirmation that are so unsound that they show the need for more justices like her. Exhibit A is an essay by Harvard Law Professor Laurence Tribe, arguing that if the Senate is tied 50-50, Vice President Pence cannot as a matter of constitutional law cast the decisive vote. The nomination is so closely contested that if his view were accurate, it could be the difference between confirmation and rejection.

Tribe is the most famous constitutional law professor of his generation, educating thousands of students at Harvard Law School on how to interpret the Constitution. But if this article is an indication of what he has taught, a constitution construed by his acolytes will go down the memory hole, to be replaced by a fundamental law that is shaped to meet the demands of the left-liberal moment. The influence of law professors like him on generations of law students shows why it is all the more necessary to confirm justices to the Supreme Court who will help create a legal culture in which the Constitution is read according to its text as originally understood.

The most relevant text in this case is obvious and clear: “The Vice President . . . shall be the President of the Senate but shall have no Vote, unless they be equally divided.” Professor Tribe never actually quotes this language, no doubt because it is hard to deny what any reasonable reader would believe it means: The Vice President has the authority to break ties whenever the Senate is equally divided.

Against this clear language, Tribe’s first argument relies on Federalist 69 where Alexander Hamilton contended that the Constitution gave the President less power than the British monarch and the governors of some states. Hamilton noted that the New York Governor’s appointment power was greater than the President’s because the Governor has a casting vote if the council that votes to confirm a candidate is divided, but the President has no such vote under the Constitution: “In the national government, if the Senate should be divided, no appointment could be made; in the government of New York, if the council should be divided, the governor can turn the scale, and confirm his own nomination.”

The key language proffered by Tribe is: “if the Senate should be equally divided, no appointment can be made.” But this language does not directly contradict the Vice President’s power clearly outlined in Article I. Without the Vice President’s vote, it is true that if the Senate is equally divided no appointment can be made. A 50-50 vote defeats a nomination. To be sure, in the situation of the New York State Constitution, the Governor would always be expected to vote for his nominee, so that situation of equipoise may not arise. But one must remember that at the time the Constitution was written the President and Vice President did not run as a ticket. The Vice President was the candidate with the second most electoral votes. Indeed, the Vice President was as likely to be an opponent of the President as he was to be an ally. This was the case with Vice President Thomas Jefferson during the presidency of John Adams. Thus, it was not at all clear a Vice President would intervene on behalf of the President.

In any event, even if Hamilton assumed that the Vice President could not break ties in cases of appointments, a single sentence from one of the Founders, no matter how illustrious, cannot overcome the plain meaning of the text. Even if one believed in original intent, one person does not show the collective intent of the Convention and, as Chief Justice John Marshall observed of a legal interpretive rule at the time, the spirit of the document is to be “collected chiefly from the words.”

Tribe then relies on the drafting history of the Appointments Clause. He notes that “the Framers first considered a provision that ‘Judges shall be nominated by the Executive, and such nomination shall become an appointment if not disagreed to by the [Senate].’” He then points out that the language that appeared in the Constitution as enacted is different from this initial language: “[t]he President . . . shall nominate and by and with the advice and consent of the Senate appoint . . . Judges of the Supreme Court.”

The kind of result-oriented spin that Tribe tries to give to our Constitution is precisely what sound originalism will thwart.

Tribe argues that this reformulation shows that the Vice President cannot vote on Supreme Court appointments, because the only difference this change in language would make is that nominations would fail on a tie vote, since the first version required the Senate to affirmatively disagree with the President to kill a nomination. But this claim is not right. In the first version, if the Senate did not vote at all after a reasonable time, as sometimes the Senate does not do, the nomination would appear to be approved, but it would fail under the actual language of the Constitution, which requires affirmative consent. Indeed, if we are engaging in speculation, the probable reason the language was changed was that the first version was less clear and would have led to questions about what exactly would happen when the Senate did not vote at all after a reasonable time. But the larger problem with Tribe’s analysis is that his speculation on the reasons for a drafting change in another clause provides no legal justification for departing from the clear meaning of the constitutional provision that grants the Vice President a casting vote when the Senate is divided. Certainly, nothing in the Appointments Clause as enacted undermines that meaning.

Finally, Tribe also ignores practice: Vice Presidents have cast votes on appointments for almost 200 years without, to my knowledge, anyone raising these concerns. It is true that the early votes were on executive branch appointments, not judicial appointments, but that difference is irrelevant to his principal arguments. Tribe tries to conceal the fact that his analysis would apply to executive as well as judicial appointments by putting ellipses in his quotation of the Appointments Clause rather than quoting it in full. The Appointments Clause, however, does not just concern justices of the Supreme Court, but “Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States.” Thus, the practice of Vice-Presidents casting votes on executive appointments would be relevant to judicial appointments as well, even if the Clause on the Vice President’s voting were ambiguous and needed to be liquidated by practice.

The first instance of a Vice-President using a casting vote on appointments was in fact a famous and consequential incident in American history. Vice President John C. Calhoun voted against the appointment of Martin Van Buren to be Ambassador to the United Kingdom. To be sure, that vote was strictly speaking unnecessary, because the vote would have been otherwise tied on the motion for confirmation and would have thus defeated the nomination. But the vote had great symbolic significance. Van Buren’s many opponents in the Senate, including Daniel Webster, arranged the vote to be a tie so that Calhoun could cast his vote to make the rejection more emphatic and politically damaging. And Calhoun was a main rival of Van Buren to succeed Andrew Jackson. Calhoun was delighted with the prospect: Van Buren’s defeat at his hands “will kill him, sir, kill him dead. He will never kick, sir, never kick.”

Calhoun was wrong in his prediction. The raw politics and ambition behind Van Buren’s defeat actually increased sympathy for the “little magician.” He replaced Calhoun as Vice President for the 1832 election and became Jackson’s successor. But Calhoun’s act was so politically important and controversial that it is hard to believe that constitutional doubts would not have been raised about the authority of this casting vote on an appointment had anyone entertained them.

The kind of result-oriented spin that Tribe tries to give to our Constitution is precisely what sound originalism will thwart. And that is the kind of jurisprudence a Justice Barrett will almost certainly provide.