Jonathan Haidt seeks technological solutions to fallen human nature.

Lego-block Hopes and Reign of Terror Dreams

The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers. Or all the noblemen. College professors. People with glasses. Kulaks. The petty bourgeoisie. Any kind of bourgeoisie, for that matter. Perhaps some of them do not entirely deserve it, considered under an abstract concept of justice. But we do not live, you and I, in any world of abstraction. We live in the hard materiality of social economics, and humanity is suffering. The ground must be cleared, even if some flowers are ploughed under with the weeds. Even if some wheat is lost with the tares.[1]

Or no—wait. The first thing we do, let’s build something new. A new science, a new architecture, a new literature. Let’s create a new poetics that properly expresses the new man. A new science that reaches beyond what had been thought the limitations of the human. Let us build us a tower, whose top reaches toward the heavens, and make a name for ourselves. With the knowledge of our new Atlantis, the logic of our new Organon, we have the means to construct a heavenly city unlike any seen before.[2]

And there, in brief, are the two defining impulses of Enlightenment, the dual urges that have driven modern times since its first moments: the bulldozer and the Lego blocks. At times modernity wants to smash the past, and at times modernity wants to assemble the future. Sometimes we want to strangle the last king with the guts of the last priest, and sometimes we want to build a spaceship. Uproot the crooked timber of old humanity, or plant a different forest. Rage against the world that is, or rave about the world to come.[3]

Perhaps there’s nothing distinctly modern about these impulses. By definition, the desire for change always involves a nightmare about what’s wrong and a dream about what’s right.[4] But when we look at the Enlightenment, we see the elements elevated to the level of principles. If you ever wondered why the end of the 18th century contained a thousand French sans–culottes trundling Marie Antoinette to the guillotine and a thousand tinkerers inventing new wood-burning stoves, lightning rods, and apple-corers, here’s the answer: Modernity holds both an urge to destroy something old and an urge to create something new.

The paired impulses of modernity are often intertwined, of course, and their different mixings produce different results.[5] In America, the complaints of the Declaration of Independence are matched with the assembling of a government in the Constitution. The French revolutionaries were motivated by their rejection of the king but also their embrace of the new rationalism. The Russian communists had an analysis of the existing system’s evils, which it used to sell the joys of the coming workers’ paradise.

History has taught us that, in general, the less sweeping the revolution, the more survivable it will be for those caught in the midst of it—and, conversely, the grander the revolution’s aims, the more deadly its damage. Even the most dedicated of Lego-builders keep a bulldozer parked nearby. Simply as a cultural matter, the promise of change can turn with astonishing speed into anger at those fingered as somehow preventing the future from arriving. It was for a reason that the scientists working on stem cell research in the late 1990s were coopted so quickly into the political fights of the early 2000s. The desire to plow down the people standing in the way was palpable. It’s palpable today.

Late-modern radicalism, however, has kept its will to undo the past even as its vision of the future has grown rather blurry. The revolutionary impulse in Western culture has lacked much of a horizon since the fall of Soviet communism in Europe, and it’s left the culture without any well-formed Progressive map to point the way. All we have on the Left is a grinding anxiety about how rotten the present is: an inchoate feeling that surely there must be something better than this, and a near-religious sense of outrage and dread.[6]

The destructive, clear-the-ground portion of modern feeling has always been prone to kind of magical thinking—to the point that it has occasionally offered destruction as itself a creative force. So, for example, in his once-infamous introduction to Frantz Fanon’s 1961 The Wretched of the Earth, Jean-Paul Sartre argued that Algerians needed to kill French colonists; only in the act of murder could they find the psychological resources to shake off the mentality of the oppressed. But even without direct praise of murder, the scorching of the earth can come to seem sufficient, as though clearing the field is all that’s required for good crops to grow.

The logic of escalation finds its premise at that moment. If we know what’s right, and still paradise hasn’t arrived, then there must be a force resisting us. There must be a barrier whose destruction will magically allow the otherwise natural flow.[7] By any objective measure, we live in the richest, least warlike, most equitable, least bigoted, and best fed era in the history of the world. But the new heaven and the new earth are not yet here, and somehow that makes us even more angry than the open evils used to. And so we undertake the hunt to find the last vestiges of the old sins. Eradicating them has to be the way, all by itself, that we can compel the dawning of the new day.

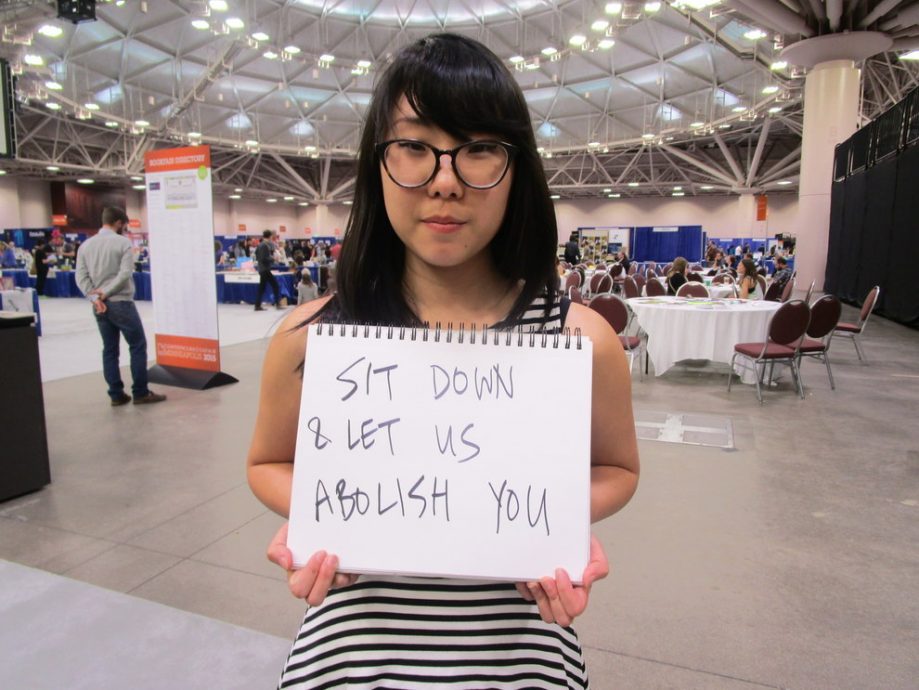

On April 16, 2015, the Association of Writers and Writing Programs posted a picture of a young woman with, it said, a message for the “Straight White Male” publishers who have kept her, and those like her, from achieving literary success. In her hands was a notebook page that read: “Sit down & let us abolish you.”

And isn’t that it, really? The bulldozer of modernity, tearing up the field once more, in the hope that this time the human condition will be remedied and the good crop will miraculously grow. The young woman with the notebook message didn’t look particularly murderous or even unpleasant. And the Association of Writers and Writing Programs was founded in 1967 for the more-or-less laudable purpose of bringing together college writing departments—in order to “foster literary achievement, advance the art of writing as essential to a good education, and serve the makers, teachers, students, and readers of contemporary writing.”

But precisely in that ordinariness, we can see the pattern. You want to know how the Lego-block hopes of the early French Revolution morphed into the bulldozer of the Reign of Terror? Probably much like this: by reaching a point where it seems quite ordinary for a young woman to announce that she wants to abolish those who are in the way.

[1] Lawyers, quoted from Henry VI, Part II (IV:ii:73). The example of noblemen, in the French Revolution. Professors, in China’s Cultural Revolution. Glasses-wearers, in the killing fields of Cambodia. Kulaks, in Lenin’s 1918 Hanging Order, and the petty bourgeoisie, from his 1905 book Petty-Bourgeois and Proletarian Socialism. Hard materiality, in Stalin’s Dialectical and Historical Materialism (1938). The parable of the wheat and the tares, from Matthew 13:24-30.

[2] Modernist architecture in the Futurist manifesto. Modernist poetry in Ezra Pound’s Imagism. The Tower of Babel, from Genesis 11:4. Knowledge in Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis and logic in Aristotle’s old Organon. The new construct, from Carl Becker’s The Heavenly City of the Eighteenth-Century Philosophers (1932).

[3] The crooked timber image is from Immanuel Kant. Strangling the last king, from Diderot (via Jean Meslier).

[4] And so, of someone who takes “extraordinary action . . . to order a kingdom or constitute a republic,” Machiavelli writes: “It is very suitable that when the deed accuses him, the effect excuses him; and when the effect is good, as was that of Romulus, it will always excuse the deed; for he who is violent to spoil, not he who is violent to mend, should be reproved.”

[5] A point made particularly by Gertrude Himmelfarb in her 2004 book, The Roads to Modernity: The British, French, and American Enlightenments.

[6] Hence the title of my 2015 book An Anxious Age, and the argument I laid out in a long 2014 essay in the Weekly Standard called “The Spiritual Shape of Political Ideas.”

[7] Among the favorite modern answers: Jews, aristocrats, and Catholics.