Lincoln, Lewis, and Our Politics of Passion

There is much to dislike about contemporary American politics. Yet perhaps the most troubling element of our present discontents lies beyond our mere partisan differences. It involves a distinctive politics of passion that could, if left unbridled, lead to the ruin of our experiment in republican self-government. The riots throughout the summer of 2020, accompanied by the “Storm on the Capitol,” serve as flashpoints of this entrenching reality. While both events differ in their origin and purpose, they represent epiphenomena of our current political moment.

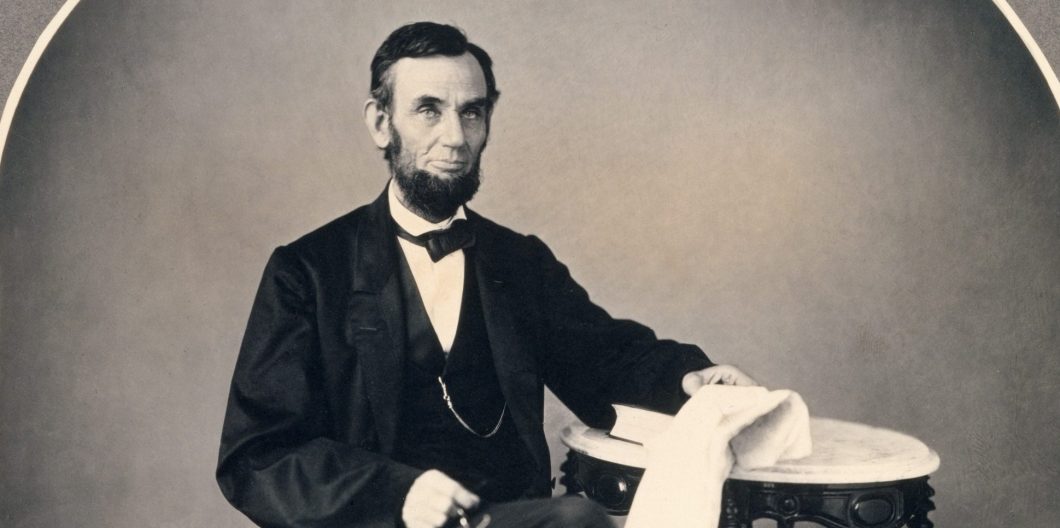

Yet all is not lost. Americans would do well to reacquaint themselves with two voices of reason—one domestic, one foreign—who together provide a common teaching that does not eschew passion but elevates passion as the handmaiden of informed reason. In Abraham Lincoln and C.S. Lewis, one finds a cogent teaching on our politics of passion.

Abraham Lincoln’s Lyceum

The young Abraham Lincoln, at age 28 in 1838, delivered his famed The Perpetuation of our Political Institutions at the Young Men’s Lyceum in Springfield, Illinois. Lincoln crafted the speech in the context of a surge of mob violence against blacks and their abolitionist sympathizers. He identified an “increasing disregard for law” pervading the country, and “a growing disposition to substitute the wild and furious passions, in lieu of the sober judgement of Courts; and the worse than savage mobs, for the executive ministers of justice.”

Lincoln identified how, under such lawlessness, even the law-abiding will lose hope in their institutions: “men who love tranquility, who desire to abide by the laws, [and] who would gladly spill their blood in the defence of the country; seeing their property destroyed; their families insulted, and their lives endangered; their persons injured…become tired of, and disgusted with, a Government that offers them no protection…”

To fortify against mob law, Lincoln provides the prescription:

As the patriots of seventy-six did to the support of the Declaration of Independence, so to the support of the Constitution and Laws, let every American pledge his life, his property, and his sacred honor;—let every man remember that to violate the law, is to trample on the blood of his father, and to tear the character of his own, and his children’s liberty. Let reverence for the laws, be breathed by every American mother, to the lisping babe, that prattles on her lap—let it be taught in schools, in seminaries, and in colleges; let it be written in Primers, spelling books, and in Almanacs;—let it be preached from the pulpit, proclaimed in legislative halls, and enforced in courts of justice. And, in short, let it become the political religion of the nation; and let the old and the young, the rich and the poor, the grave and the gay, of all sexes and tongues, and colors and conditions, sacrifice unceasingly upon its altars.

For Lincoln, our passions must be turned towards the Constitution and laws, respecting the work of the “patriots of seventy-six” and realizing that for one to violate the law carries multi-generational effects, on the “blood of his father” and the “character of his own, and his children’s liberty.”

When Lincoln concludes his speech calling for a replacement of the Founding generation—“the pillars of the temple of liberty”—with new pillars “hewn from the solid quarry of sober reason,” one should not understand these new pillars as lacking passion whatsoever. In his rousing conclusion, he states, “Reason, cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason, must furnish all the materials for our future support and defence. Let those materials be moulded into general intelligence, sound morality, and, in particular, a reverence for the constitution and laws” (emphasis added).

A properly developed intelligence, a sound morality, and a reverence for the Constitution and the laws require more than pure cerebral recognition. A Lincolnian “reverence” for the Constitution and the laws is, according to Diana Schaub, a kind of “reasonable passion,” or passion in conformity with enlightened reason.

Lincoln highlights how the “scenes of the revolution” powerfully impacted “the passions of the people as distinguished from their judgement.” The Revolution turned the people’s passions collectively against a common foe—the British. While the scenes of the Revolution were now gone, he makes clear that they can be recalled: “I do not mean to say, that the scenes of the revolution are now or ever will be entirely forgotten…In history, we hope, they will be read, and recounted, so long as the Bible shall be read.”

Thus, an overly rigid interpretation of Lincoln’s speech may leave one thinking “cold, calculating reason” is alone our guide. Yet, Lincoln’s speech also underscores the important role of channeling passions towards just purposes, having a proper love of country as a result of proper reasons for such a love. What is somewhat oblique in Lincoln’s speech is more explicit in the work of C.S. Lewis.

Studying Lincoln and Lewis in our own time helps us contextualize where we have been and where we are now, while supplying not only the insight, but also the passionate inspiration, to know what to do next and how to do it.

C.S. Lewis’s Sentiments

For C.S. Lewis, the great Christian apologist of the 20th century, perhaps his most philosophical work is his The Abolition of Man. Like all great books, it speaks to more than one topic, though one is of particular interest here: sentiments.

In this work, Lewis is concerned about educational practices that would diminish one’s ability to identify objective truth. He finds in education a key to such a predicament, for while modern educators may try to fortify young minds against emotion, Lewis claims, “My own experience as a teacher tells me the opposite…The task of the modern educator is not to cut down jungles but to irrigate deserts. The right defence against false sentiments is to inculcate just sentiments.”

For Lewis, in a Platonic formulation, “the head rules the belly through the chest.” There is a correspondence between our head and our hearts that can direct man towards good and noble actions. Thus, it proves pivotal to develop the right sentiments—those emotions properly merited by objective reality. Those sentiments for Lewis must be taught, following the instruction of Aristotle, to help pupils like and dislike what they ought.

To remove this uniquely human function would be to abolish man as man, to create “men without chests.” Lewis describes the cultivation of proper sentiments in the following manner:

We were told it long ago by Plato. As the King governs by his executive, so Reason in man must rule the mere appetites by means of the spirited element. The head rules the belly through the chest—the seat, as Alanus tells us, of Magnanimity, or emotions organized by trained habit into stable sentiments. The Chest—Magnanimity—Sentiment—these are the indispensable liaison officers between cerebral man and visceral man. It may even be said that it is by this middle element that man is man: for by his intellect he is mere spirit and by his appetites mere animal.

Properly trained sentiments prove necessary for the fully developed human being—one who can distinguish truth from falsehoods; identify, beyond our own perspectives, an objective moral order (what Lewis refers to as the Tao); and express a mature and proper love for what is true, good, and beautiful.

Like Lincoln, Lewis understood the correspondence between reason and passion. While reason must be prioritized, it mustn’t tyrannize. Reason must correspond with properly cultivated sentiments—sentiments which, to use Lincoln’s words, revere a regime that adheres to the “ends of civil and religious liberty.”

Our Politics of Passion

What Lincoln and Lewis taught is once again our burden—we must enliven a citizenry to the sentiments proper to perpetuating the American regime. In Abolition of Man, one finds a philosophical assessment of the role of education and the proper relation between reason and emotions, themes found in Lincoln’s speech as well. Taken together, a teaching emerges providing Americans a north star to navigate the current storms.

In the current moment, Americans must return to first principles, those “principles of the Revolution,” as the Federalist put it—the unifying principles of equality, natural rights, and government by consent, preserved by a Constitution designed to “secure the Blessings of Liberty.” Yet, if we cannot accomplish this task, “if destruction be our lot,” as Lincoln warned, then “we must ourselves be its author and finisher.”

Consider the cultivation of patriotism. Both Lincoln and Lewis understood there must be a mature gratitude for one’s country that would induce one to make the ultimate sacrifice for their nation. At Gettysburg in 1863, Lincoln praised the “brave men” who “gave their lives that the nation might live.” Likewise, Lewis in The Abolition of Man wrote of how it is more than mere self-interest or instinct that would compel a solider to die for his nation. He also wrote poignantly in The Four Loves of a kind of informed patriotism, where proper love of country merits affection but “becomes a demon when it becomes a god.”

Thus, a mature love for those first principles articulated in the Declaration and embodied in the Constitution—which transcend contemporary partisan differences—could present an antidote to a currently debased politics of passion, unifying our actions toward noble pursuits. As Lincoln taught in the Lyceum Address, one should obey bad laws and work peacefully through the political process to overturn them. Such is the way of an orderly, republican citizenry unified by preserving the Constitution—a citizenry that displays reverence for the laws made under the Constitution even as it attempts to alter them. A common commitment to such principles may also compel us to what Lincoln called our “better angels,” restoring our mutual “bonds of affection.”

Such a project will require playing the long game, and it must be undertaken on several fronts: within the family, neighborhoods, schools, and, of course, our politics. These are all institutions critical to the perpetuation of the American regime, and they all teach citizens what it means to be civically informed.

Consider the critical role of education and politics. Both are intimately intertwined, as what is taught in the schools may have political implications. As Lewis wrote, a true education is one that does “not cut men to some pattern they [the educators] have chosen,” but “handed on what they had received: they initiated the young neophyte into the mystery of humanity which over-arched him and them alike. It was but old birds teaching young birds to fly.” What Lewis describes is not indoctrination but a true education into how to think about great truths. In America, it is an education that can open the mind to know, and properly love, those very truths necessary to the perpetuation of a free people and a republican form of government.

As Charles R. Kesler has noted, the American founders engaged in an intentional effort to educate the citizenry in moral and civic virtue, with the end of ensuring “a common dedication to republican principles…touchstones of American citizenship.” Indeed, writing in 1784, George Washington noted the following to an author of a book on education: “[T]he best means of forming a manly, virtuous and happy people, will be found in the right education of youth…qualifying the rising generation for patrons of good government, virtue, and happiness.”

Not only did this theme of civic education pervade many speeches from leading founders, but it made its way into laws as well. In the Northwest Ordnance of 1787, Article III charges that “Religion, Morality, and knowledge being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, Schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged.” Such schools would inculcate the skills and virtues necessary for republican self-government, and they provide a guide for us still today. The recent revival of classical education throughout the nation proves promising, as many of these schools hold moral and civic virtue as key pillars of their educational models.

Still, it is no easy task to properly educate a citizenry to appreciate the nation’s principles and to know how to preserve them. Thus, like a great ocean liner performing an about-face, this project will not happen instantaneously, and it will face resisting waves. Yet being clearheaded about where we are can help us chart that proper course ahead.

As Lincoln also eloquently put it, “If we could first know where we are, and whither we are tending, we could better judge what to do, and how to do it.” Studying Lincoln and Lewis in our own time helps us contextualize where we have been and where we are now, while supplying not only the insight, but also the passionate inspiration, to know what to do next and how to do it.