The real legacy of woke capital gives shape to an outrage style in politics, one that ultimately threatens free markets.

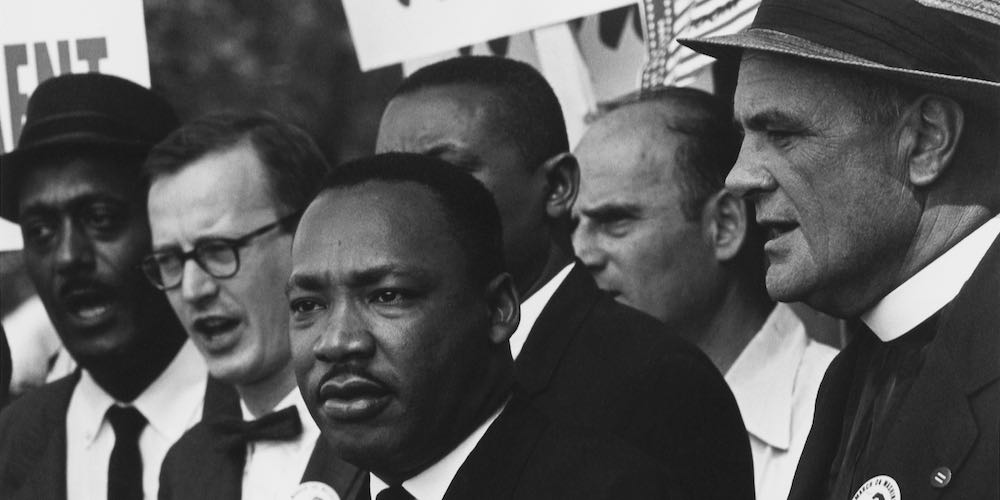

Martin Luther King's Personalist Vision

It is now a familiar fact that political polarization in the United States is at a 40-year high. We have what is known as “affective polarization,” which is rooted more in hostile attitudes toward political opponents than in disagreements over policy. In the face of rising political hostility, some have sought inspiration in the legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr. Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt invoke King as an exemplar of the “common-humanity identity politics” that they propose as an alternative to the “common-enemy identity politics” so often employed by both the left and the right. And in a number of recent works, Martha Nussbaum encourages us to follow King’s example in learning to subdue divisive “political emotions” such as anger, and to operate instead on a basis of the kind of agapē love endorsed by King.

Such appeals are largely salutary, and are more in keeping with the spirit of King’s thought and work than are attempts to assimilate King to forms of Critical Social Justice thought and activism. Strangely omitted from these appeals to King, however, is any serious consideration of the deeper beliefs that guided him in his approach to social justice. Lukianoff and Haidt focus mainly on King’s unifying rhetoric:

Part of Dr. King’s genius was that he appealed to the shared morals and identities of Americans by using unifying languages of religion and patriotism. He repeatedly used the metaphor of family referring to people of all races and religions as “brothers” and “sisters.” … King’s most famous speech [the “I have a dream” speech] drew on the language and iconography of what sociologists call the American civil religion.

Although Nussbaum pays considerable attention to King’s moving vision of a just society as elevated in his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, her emphasis is on cultivating the emotions to which King’s vision naturally inclines us, rather than cultivating belief in the vision itself. But to focus on King’s rhetorical choices and their emotional impact in isolation from their doxastic bases, is to cast King as a sophist, rather than as the philosophically trained theologian that he was. Indeed, the fundamental differences between King and practitioners of common enemy identity politics are not rhetorical or methodological, but metaphysical: the reason King spoke as he did, and the reason he practiced “common-humanity identity politics,” is that he had a clear philosophical vision of our common humanity, understood not merely as an inspiring phrase or idea, but as a bedrock reality.

In a frequently excerpted portion of his first book, King explained:

I studied philosophy and theology at Boston University under Edgar S. Brightman and L. Harold DeWolf. …It was mainly under these teachers that I studied personalistic philosophy—the theory that the clue to the meaning of ultimate reality is found in personality [i.e., personhood]. This personal idealism remains today my basic philosophical position. Personalism’s insistence that only personality—finite and infinite—is ultimately real strengthened me in two convictions: it gave me metaphysical and philosophical grounding for the idea of a personal God, and it gave me a metaphysical basis for the dignity and worth of all human personality.

For someone of a traditional, philosophical bent like King, the identification of a “basic philosophical position” is of profound significance. “Basic” here means, not simple, but fundamental; thus, a person’s “basic philosophical position” is the fundamental lens through which he sees his life and world. As such, it constrains, conditions, and colors everything else the philosophically minded person believes, says and does. For instance, King’s doctoral dissertation was an exercise in developing and defending a view of God consistent with his Personalism. King’s Civil Rights work, too, was as much an extension of his Personalism as of his Christianity, not merely because his Christianity was infused with Personalistic thought, but because Personalism itself gave King “a metaphysical basis for the dignity and worth of all human personality.”

The Personalism King embraced at Boston University was one manifestation of a broad tradition of “personalistic philosophy” that had been developing in Europe since the late 18th century. Like all such traditions, it gave rise not to a single, “orthodox” position, but to a number of competing variations on a common theme. One way of articulating that common theme is to say, as the once-prominent American Personalist John Wright Buckham put it, Personalism is the attempt to see reality “sub specie personalitatis.” Or as King put it, “only personality… is ultimately real,” and hence “the clue to the meaning of ultimate reality is found in personality.” When Personalists spoke of “personality,” they did not mean a set of “personality traits.” Rather, they meant personhood itself, considered not as an abstraction, but in concrete manifestation. To say that “personality is ultimately real” is to say that persons are ultimately real. Thus, Thomas Buford uses “personality” and “person” interchangeably in articulating Personalism’s core commitment:

Personalism is any philosophy that considers personality the supreme value and the key to the measuring of reality. … Personalists claim that the person is the key in the search for self-knowledge, for correct insight into reality, and for the place of persons in it.

Personalism’s understanding of personhood was built from the accumulated insights of Western philosophy and Christian theology, especially as these came together in Kant and a certain strain of post-Kantian Idealism. However, the forms of Personalism that ultimately had the greatest impact – not only the “Boston Personalism” that King was trained in, but also forms associated with Jacques Maritain, the mastermind behind the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and with Pope John Paul II and the Polish Solidarity movement of the 1980s – broke from Absolute Idealism in favor metaphysical frameworks more conducive to characterizing persons as genuine individuals with a common nature. For these Personalists, persons are independently-existing individuals of roughly the sort that Aristotle called “substances,” characterized by consciousness, free will, and an array of cognitive and affective capacities capable of yielding self-consciousness, intersubjectivity, and insight into a broad range of truths, empirical, logical, moral, and so on.

Personalism is similar to some prominent versions of existentialism in emphasizing interiority (a.k.a. subjectivity) and free will, or agency, as central to personhood, but Personalists characteristically did not take this to entail any form of subjectivism. On the contrary, Personalists tended to see human agency as operating in a domain of objective and rationally knowable facts, including, most importantly, moral facts. The most influential versions of Personalism understood the moral domain in terms of natural law theory – thus King, in his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” invokes Augustine and Aquinas to elucidate the distinction between just and unjust laws before formulating the distinction in personalist terms: “Any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust.”

For the Personalist, the capacity to align oneself with moral reality freely and on the basis of one’s own insight and understanding constitutes the heart of personhood – as British Personalist Henry Sturt observed in 1902, our sense of ourselves as moral agents encapsulates “the cardinal facts of our experience.” This capacity is also what makes persons so valuable. As the first historian of Personalism, A.C. Knudson, put it, personhood “implies a certain degree of privacy, and this privacy has about it something sacred.” It is from within the sacred interior space of our private thoughts and feelings that we exercise moral agency, and it is mainly in virtue of this capacity that the Personalists followed Kant in affirming that persons possess that unique type and degree of intrinsic value designated by the term “dignity.”

By sorting people into groups of innocent victims and complicit beneficiaries of systemic injustice on the basis of their social identities, CSJ employs a cognitive frame virtually guaranteed to evoke hostile attitudes and behaviors, just as we see in common enemy identity politics and affective polarization.

It was because of Personalism’s insistence upon the bedrock reality of persons thus understood that King could credit it with giving him “a metaphysical basis for the dignity and worth of all human personality.” This in turn grounded King’s vision for a just society as one pervaded by agapē love (“the beloved community”) and his commitment to nonviolence as the only acceptable means for achieving that end.

Clearly, King’s personalist understanding of our common humanity stands in opposition to many contemporary sensibilities. These include a scientism-driven skepticism about free will and about moral facts – matters too complex to take up here. It also stands opposed to the contemporary tendency to pay far too much attention, in thinking about persons, to what philosophers since Aristotle have called “accidental” features of the human being. These are attributes incidental to our fundamental metaphysical status as persons, like particular arrays of personality traits, or of the attributes mapped by demographic categories like race and gender. Common-enemy identity politics depends on our willingness to view ourselves and others primarily in terms of such features, for only thus can we be divided into warring camps.

Consider how this takes shape in Critical Social Justice (CSJ) thought and activism, which is widely taken to be a primary driver of “cancel culture” and common-enemy identity politics. As Helen Pluckrose explains, CSJ “…is a specific theoretical approach to addressing issues of prejudice and discrimination on the grounds of characteristics like race, sex, sexuality, gender identity, dis/ability and body size.”

These characteristics, which are at most secondary to one’s identity from King’s Personalist perspective, are made primary in CSJ thought. According to CSJ, such characteristics correspond to socially-constructed roles or “identities” which mark one as either a victim or a beneficiary of the injustices around which our social institutions are supposedly built, and which they supposedly perpetuate. The CSJ concept of “intersectionality” notes that each person bears multiple social identities, and that bearing multiple “oppressed” identities can compound one’s unmerited social disadvantage. According to CSJ, this “intersectional lens” is uniquely capable of revealing systemic injustices to which the privileged are normally blind; hence its adoption is required in order to achieve a more just society. So goes the theory. But, in practice, it turns out that viewing one’s fellow citizens as “ensembles of social relations” that mark them as opponents in a perpetual struggle for power tends not toward justice, but toward mutual disdain, animosity, and political dysfunction. This is no fluke: by sorting people into groups of innocent victims and complicit beneficiaries of systemic injustice on the basis of their social identities, CSJ employs a cognitive frame virtually guaranteed to evoke hostile attitudes and behaviors, just as we see in common enemy identity politics and affective polarization.

The tendency to think of people in terms of their surface attributes, rather than those that constitute their metaphysical depths, goes well beyond the influence of CSJ. In fact, David Brooks, in a 2018 effort to rekindle awareness of Personalism, imports this tendency into Personalism itself. After correctly noting that “Personalism is a philosophic tendency built on the infinite uniqueness and depth of each person,” he goes on to construe this uniqueness not in terms of each person’s being a numerically unique source of moral agency, but in terms of their being bearers of unique arrays of “accidents”:

[P]eople are always way more complicated than you think. We talk in shorthand about ”Trump voters” or ”social justice warriors,” but when you actually meet people they defy categories. Someone might be a Latina lesbian who loves the N.R.A. or a socialist Mormon cowboy from Arizona.

Thus, when Brooks goes on to say that “the first responsibility of personalism is to see each other person in his or her full depth,” he means that “you just don’t regard people as a data point, but as emerging out of the full narrative, … you try, when you can, to get to know their stories, or at least to realize that everybody is in a struggle you know nothing about.”

Coming to know another person in terms of their unique attributes is a wonderful thing, and Personalism certainly encourages this to the extent that it is possible. But there are profound limits to what finite persons can achieve in this vein. It is therefore not a feasible basis for a social ethic. Instead, the first responsibility of Personalism is to see each other not in terms of our qualitative uniqueness, but in terms of our common personhood. Adopting the lens of common personhood enables us to recognize any and every person as a bearer of dignity, worthy of respect and even love, without knowing anything else about them. This is the key to King’s “common humanity identity politics.”

As King said in a 1960 sermon, “the basic thing about a man is not his specificity but his fundamentum,” i.e., his fundamental nature as a person. And proper moral regard for persons, which King understood in terms of agapē love, “does not begin by discriminating between worthy and unworthy people, or any qualities people possess.” That is, agapē is not interested in the qualitative differences between people, but in what all persons are due simply as persons. For King, agapē is not an emotion, but rather a settled disposition of the will to recognize and respond appropriately to personhood wherever it is encountered; it is “understanding and creative, redemptive goodwill for all men.” Thus, in his final book, King calls for “a genuine revolution of values,” which

means in the final analysis that our loyalties must become ecumenical rather than sectional. Every nation must now develop an overriding loyalty to mankind as a whole in order to preserve the best in their individual societies. This call for a universal fellowship that lifts neighborly concern beyond one’s tribe, race, class, and nation is in reality a call for an all-embracing and unconditional love for all men.

This is a profound expression of the “common-humanity identity politics” that makes King a worthy role model in our exceedingly polarized times. But King’s moral vision was predicated upon his Personalist understanding of human persons and human dignity, and it is not clear just how far the former is separable from the latter. Presumably one need not be a card-carrying Personalist in order to recognize and respect our common humanity. An “overlapping consensus” on the moral upshot of Personalism is possible. But it is fanciful to suppose that King’s rhetoric will have the same symbolic and emotional power for people who do not hold sufficiently similar beliefs about human persons.