Myths and Realities of Drug Addiction, Consumption, and Crime

In this third post in opposition to drug legalization (here are the first and second), let me address the argument that the crime rate could be much reduced by legalizing the distribution and possession of currently illicit drugs.

This idea is attractive because people who take drugs allegedly commit many crimes in order to pay for them. There are, of course, stimulant drugs that make people more likely to commit acts of aggression or violence because the drugs themselves—amphetamines, cocaine, and cannabis among others—cause paranoia. But these crimes are not the acquisitive crimes (theft, burglary) that people usually mean when they speak of the crime that drug addicts commit.

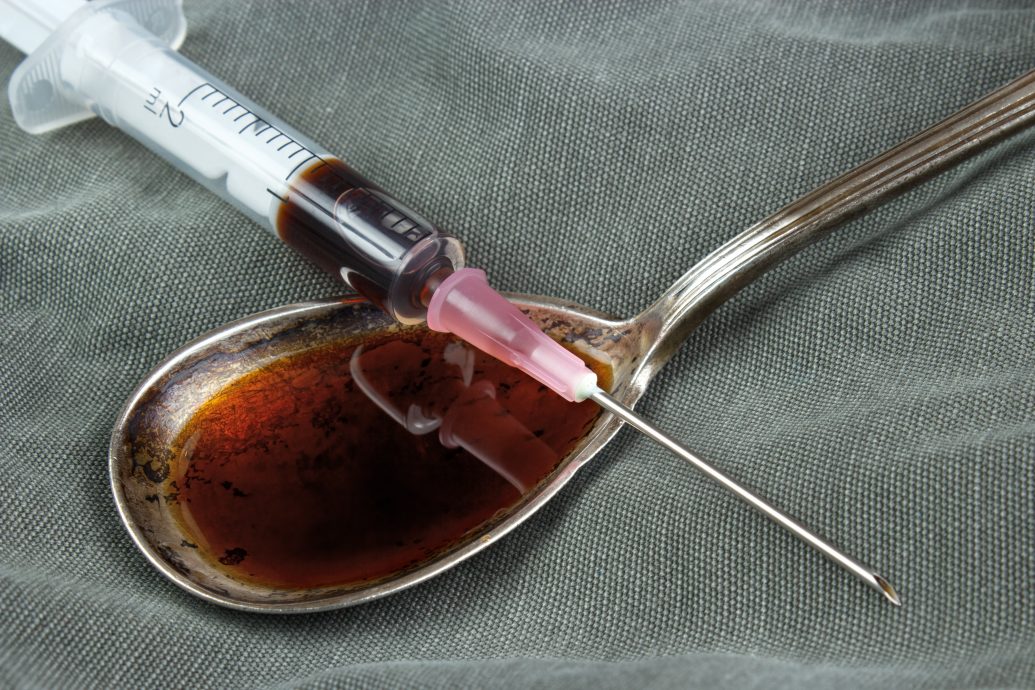

There is no pharmacological reason why people who take heroin should commit crimes; the case is rather the reverse. Heroin has both euphoriant and tranquillizing properties, neither of which one would expect to lead to the commission of crime. And yet many heroin addicts do commit crimes, often repeatedly and in large number. Why? The standard answer: to “feed their habit,” to use an expression I have heard hundreds of times. According to this view, taking the drug renders them incapable of normal, legitimate work; but such is their overwhelming and irresistible compulsion, their need, to take the drug once they have become addicted to it that they must obtain it somehow. Crime is their way of squaring this circle.

Among the flaws in this view is its implicit explanation of how and why people become addicts in the first place. In fact, most heroin addicts choose to become addicted and indeed have to work at it. Not only do heroin addicts on average take the drug intermittently for 18 months before becoming physically dependent on it, but they have a lot to learn—for example where and how to obtain supplies, how to prepare the drug, and (if they inject) how to inject it. Most people have a slight natural revulsion against injecting something into their veins, a revulsion that has to be overcome. This speaks, then, of determination, not of a condition fallen into by accident.

The process of learning is a social one: there are teachers and taught. Those who become addicted are very largely a self-selected group, for no matter how widespread or prevalent heroin addiction becomes in a community or population, it never affects everyone. In other words, it is a choice.

Once addiction becomes widespread, its consequences are known to new recruits: they know perfectly well in advance how addicts live. One of the attractions, especially for those who feel themselves in opposition to or let down by society at large, of what might be called the heroin way of life is its transgressiveness. Opposition to the mores of one’s society is a way of achieving personal significance, however illusory or worthless in the eyes of others that significance might be; moreover the heroin addict’s life is busy and full of incident, which it might otherwise not be.

Some addicts, however, lead law-abiding lives (apart from the laws they break in buying and possessing their drug). The social class, educational level, and perhaps intelligence of these addicts can be above the average. We can all name successful artists and musicians who were heroin addicts. But this is not true of, shall we call them run-of-the-mill heroin addicts, many of whom break other laws and end up in prison. Of these, two observations may be made.

First, when they began their heroin “career,” they were fully aware of the criminality of the social milieu they were entering; most of them already had criminal propensities when they entered it. In the prison in which I worked as a doctor, for example, most of the addicts had already served a prison sentence before they ever took heroin. Since it was rare for a prisoner to be sentenced to prison on his first conviction, and since most prisoners readily confessed to me that they had committed between five and 20 times as many offenses as they were ever convicted for, their criminal activity before ever taking heroin must have been extensive. And a small percentage claimed (though I did not altogether believe it) to have become addicted in the first place while they were in prison.

Whatever the connection between crime and addiction, it is not that addiction causes crime.

The second thing to note about the life of the heroin addict who funds his drug-taking by petty crime is that it can be surprisingly strenuous. In one case in which I was involved as a witness, a group of addicts who lived together described how they would go shoplifting, or “out to work” as they called it, almost every day, from morning till night. They stole not in the town where they lived, but in the towns round about, which they rotated to reduce the chances of being caught. They paid a friend of theirs to drive them around. In a statement to the police, one of them said of a day three months earlier, “I can’t remember detail . . . but I would have been out all day stealing stuff to sell to get money for heroin. We would have got back to the flat at 7 p.m.”

Not only did they steal the “stuff,” but they had to sell it afterwards, since the “stuff” was not for their use or consumption but only to raise money, presumably at grossly discounted prices to people who knew perfectly well that they were buying stolen goods. Whatever else might be said about this group of addicts, their ability to work was scarcely in doubt. From their description of what they stole, it is not likely that they raised very much more by shoplifting than they would have raised by honest work. In fact they had never worked, but had shoplifted, before they were addicted, or addicted themselves, to heroin (one of them smoked it for more than a year before she injected it).

All of this suggests it is unlikely that altering the laws relating to drugs that are currently illicit will reduce the crime rate very significantly.

Nor can we draw firm conclusions from a country where the possession of small quantities of all drugs has been de facto decriminalized for a number of years, Portugal. Possession is dealt with in an administrative manner in Portugal, rather like a parking ticket, and leads to no criminal record. According to the statistics on Eurostat, the E.U.’s website, the crime rate in Portugal has not declined since decriminalization of drug possession, though it has in several other European countries that have not decriminalized drug possession.

Reaching well-founded conclusions is difficult because the problems with the evidence are many:

• The crime statistics can easily be manipulated by those who want to prove one thing or another.

• We cannot know what the statistics, even if honestly collected and published, would have been in the absence of decriminalization.

• Portugal is in any case a low drug-use and crime rate country, not necessarily comparable to others (including those that have experienced a reduction in the crime rate without altering the drug laws).

• And the production, distribution and sale of illicit drugs in Portugal are still criminal offenses, prosecuted as such.

All that can be said with any certainty is that the de facto decriminalization of possession of small quantities of drugs for personal use has led neither to a dramatic rise nor to a dramatic fall in the Portuguese crime rate.

To be sure, falls in the crime rate are not the only possible measure of the success or failure of the policy. The policy itself has been combined with other measures, such as increased access to rehabilitation for the addicted. The rate of transmission of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (the cause of AIDS) among injecting drug addicts in Portugal has been much reduced, for example; but this may have been the result of public propaganda for the use, and the provision, of clean needles, by which means the same effect has been achieved elsewhere. It is therefore not easy to distinguish what the effects of the decriminalization of possession have been in isolation from the other aspects of Portuguese drug policy.

Drug use has increased in Portugal since decriminalization of possession. Post hoc is not propter hoc—we do not know for certain what would have happened anyway—but there is reason for thinking that the relationship between relaxation of the law and increased consumption was causative. The consumption of a drug is affected by its cost, including its non-financial cost. The effect of price on consumption has been shown best in the case of alcohol: the lower the price, the higher the intake. (I once worked among expatriates in Africa for whom alcohol was provided nearly free of charge. About 20 per cent of them became alcoholic, which they had not been on arrival.) For many people, a criminal record is a cost they are not willing to bear. The illicit attracts, but a criminal record also deters.

An interesting research paper traced the length of people’s addictions to various drugs, including nicotine and alcohol. The duration of their addiction was inversely proportional to the repressive and regulatory measures taken against the production, distribution, sale, and consumption of the drug.

It is too early to say what the practical effects of the legalization of cannabis will be in Uruguay or the state of Colorado. One ought to be cautious in making predictions, in advance of all experience, based on theoretical possibilities. But let us suppose for a moment that such experience shows that there is no increase in consumption, no increase in psychotic reactions, no increase in road or other serious accidents, no increase in cases of addiction requiring, or at least demanding, assistance, no diversion to those too young to take it legally. What would this tell us about drug policy in general?

That will be the subject of my next and final installment on this subject.