If the right to liberty is alienable, whether despotic rule is just or unjust depends on the actual set of agreements between the people and their ruler.

Natural Law and “This Court’s Authority”

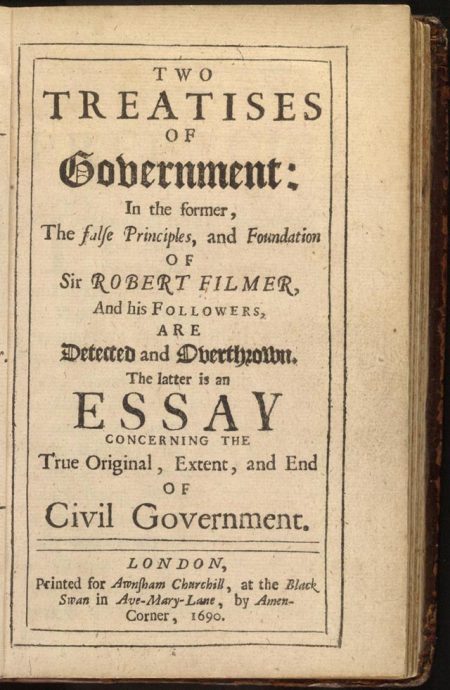

Talk about a teachable moment: I couldn’t believe it when I found a reference to “natural law” in a Washington Post article about Rowan County Clerk Kim Davis’ ill-fated conscientious objection to our new marriage regime. I couldn’t resist taking it to my students, all sophomores in a core class where we’re currently reading and discussing John Locke’s Second Treatise of Government.

Here’s what Judge David Bunning, a conservative Catholic appointed to the bench by President George W. Bush, said: “The idea of natural law superseding this court’s authority would be a dangerous precedent indeed.”

I asked my students what they thought of this statement, and several of them called my attention to a passage in today’s assignment where Locke contends that when human beings enter civil society, they give up the freedom they have in accordance with natural law “to be regulated by laws made by society” (Section 129). Society’s law seems to trump—pardon the expression—natural law. To the degree that Judge Bunning’s authority derives from human-made law, he would seem to have gotten matters right.

But, according to Locke, that’s not the whole story. In a later passage, one my students will read (if they know what’s good for them), that “the law of nature stands as an eternal rule to all men, legislators as well as others” (Section 135).

Let me rephrase Locke’s argument in Judge Bunning’s somewhat infelicitous language.

For Locke—indeed for virtually anyone who takes natural law seriously—natural law always in a sense supersedes human law because it is the source of that law’s authority. Just government, the Declaration of Independence tells us, rests on the consent of the governed, and we the people, Locke tells us, cannot consent to anything we cannot ourselves do. As we are limited by the strictures of natural law, so is any government whose actions and laws we authorize. Again, borrowing some of Judge Bunning’s language, the court’s authority derives from our authority, which is confined by natural law.

Does this mean that each of us, interpreting natural law for himself or herself, is a law unto himself or herself? Are we courting anarchy, a return to the “state of nature,” when we talk about natural law? That’s what Judge Bunning, I’m sure, fears, and it’s a prospect that any of us who understand ourselves as bound by natural law would very likely (at least in all but the most extreme circumstances) reject. We should recognize that in order to live up to our obligations—to ourselves and to others—under natural law, we need to consent to a lawmaking authority that can clarify for us what natural law means in our circumstances and see to it that the obligations it prescribes are effectively articulated and enforced. So the two passages from Locke’s Second Treatise, quoted above, are perfectly consistent with one another.

Now this most emphatically doesn’t mean that once we’ve given our consent, we never have to think about natural law again. We do so whenever, for example, we consider whether a law is just or not. In that instance, if we’re not simply expressing an idiosyncratic preference, we’re holding law to a higher standard, a natural law standard, if you will. Applying this standard doesn’t mean that we regard ourselves as entitled simply to ignore a law that we believe is unjust. Rather, we might contemplate a variety of ways of changing that law—from petitioning the government for a redress of our grievances, to voting in a new slate of legislators, to engaging in civil disobedience, all the way to making a revolution.

I’m pretty sure that, to the extent that she has thought it through, Kim Davis is all about the first three alternatives and not at all about the last one.

But let me return to Judge Bunning for a moment. If he simply rejects natural law on behalf of “this court’s authority,” then he is ultimately and (I hope) unwittingly a proponent of legislative and judicial tyranny, of the willful and arbitrary rule of men (and women) who make and interpret laws without any regard at all to a higher standard of justice.

Say it ain’t so, Judge Bunning.