Is it possible that the courts - one of our most important "auxiliary precautions" - are undermining republican liberty?

No Legislation Without Representation

“What was essentially a legislative determination… was made not by Congress or even by the Executive Branch but by a private group.” Those unsettling words come from a statement issued March 28 by Justice Alito, with whom Justices Thomas and Gorsuch joined, respecting the Supreme Court’s decision not to review yet another dispute involving the Affordable Care Act. On this occasion, though, the source of controversy was not the notorious ACA itself, but federal agencies’ willingness to hand the sovereign power to regulate over to private citizens.

A state partaking in Medicaid (as all states do) must ensure that it pays its share of the program’s expenses “on an actuarially sound basis.” Congress has not defined the term “actuarially sound”; it assigned that task to the Department of Health and Human Services. HHS, in turn, decided that a state’s Medicaid budget is “actuarially sound” if a qualified actuary applying rules set by the Actuarial Standards Board—a private entity—declares it so. The ACA imposed a large tax—some $15 billion in all at its height in 2020—on private health insurers. The Actuarial Standards Board resolved, in the name of “actuarial soundness,” to require that states cover the tax for privately run Medicaid plans. This cost the states hundreds of millions of dollars. Five states sued, arguing that HHS had improperly delegated lawmaking power to a private party. Although the district court agreed, the Fifth Circuit reversed. The arrangement was copacetic, the panel ruled, because HHS “reviewed and accepted” the private board’s standards.

Judge James Ho, joined by four other judges, unsuccessfully urged the full Fifth Circuit to rehear the case. “Our laws are supposed to be written by members of Congress,” objected Ho, “not by private interests pursuing unknown private agendas.”

Judge Ho could find no precedent for allowing an agency to “re-delegate” regulatory power to a private body without Congress’s permission.

Article I of the Constitution vests “all legislative Powers” in Congress. It is bad enough, Ho observed, when Congress violates Article I by delegating its lawmaking power to another branch of government. The case at hand was even worse, because it involved a “‘double delegation’ from Congress to public bureaucrats to private parties.” Unlike a government agency, a private board is not even “minimally accountable to the public in some way.” And although HHS could in theory overturn the board’s decisions—a point the panel had stressed—the fact remained that the board lacked the legal authority to act in the first place. Ho could find no precedent for allowing an agency to “re-delegate” regulatory power to a private body without Congress’s permission.

Noting that Congress repealed the pertinent tax during the course of the litigation, Alito, Thomas, and Gorsuch “reluctantly concurr[ed]” in the Supreme Court’s decision not to grant review. But they pushed the Court “to clarify the private non-delegation doctrine in an appropriate future case.”

That case could soon arrive, in the form of a challenge to the Federal Communications Commission’s administration of a program called the Universal Service Fund. A creature of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, the USF pays for schools, libraries, healthcare providers, and remote areas to obtain “advanced telecommunications and information services,” such as broadband. Congress empowered the FCC to define what services should be “universal,” to set the amount of money the government will collect to promote those services, and to determine how the money is spent. Even if the FCC ran the USF all by itself, the statute behind the program would raise a delegation problem.

But that’s not what the FCC does. Instead, the agency has shifted the running of the USF to something called the Universal Service Administration Company. Like the Actuarial Standards Board, the USAC is a private entity. The money for the USF comes from a tax paid by telephone companies. The USAC announces what this private-sector “contribution factor” should be—the statute does not cap the sum that can be demanded—and, if the FCC takes no action within two weeks, the figure is “deemed approved.” The FCC appears never to have rejected a USF budget set by the USAC.

The USAC openly promotes its board members’ close ties to companies and groups “interested in and affected by universal service programs.” With such people in charge, things have gone precisely as one would expect. What started as a 5.7% tax rate on end-user interstate telecom revenue, in 2000, ballooned to a 33.4% rate by mid-2021. The annual “contributions” have more than doubled over that period, hitting nearly $10 billion last year. Waste, fraud, and abuse have been rampant. (To crown all, the USF fee is highly regressive. It is a flat tax on average Americans, paid as a line item on their monthly phone bills.)

Last year a consumer-protection group, a small telecom provider, and others started lodging comments, with the FCC, contesting the constitutionality of the USAC. When the FCC ignored them, these petitioners took their cause to federal court. Cases are currently pending in the Fifth and Sixth Circuits.

The Supreme Court has considered private delegation before, including in the famous case of Schechter Poultry v. United States (1935). The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 permitted the President to adopt “codes of fair competition” presented by industry groups. Before the Supreme Court, defending a “live poultry code” drafted by New York chicken dealers and approved by FDR, the government sought to paint the private drafting of laws as a virtue. Private delegation, it claimed, would produce codes “deemed fair for each industry” by those “most familiar with its problems.”

The “live poultry code” in Schechter Poultry contained restrictions that appeared to target kosher butchers.

The Court took a different view. Sure, it said, trade groups “are familiar with the problems of their enterprise.” But “would it seriously be contended” that Congress “could delegate its legislative authority” to those groups, in the expectation that they would enact “wise and beneficent” laws for “their trade or industries?” “The answer,” the Court concluded, “is obvious. Such a delegation of legislative power is unknown to our law and is utterly inconsistent with the constitutional prerogatives and duties of Congress.”

What makes Schechter Poultry famous is that it branded the NIRA an illegal delegation of legislative power to the President. The discussion of private delegation was an aside. A year later, though, in Carter v. Carter Coal Co. (1936), the Court called private code-drafting “legislative delegation in its most obnoxious form.” This time, the denunciation of private delegation was part of the Court’s holding. Such delegation, the Court explained, “is not even delegation to an official or an official body, presumptively disinterested.” It is, rather, delegation “to private persons whose interests may be and often are adverse to the interests of others in the same business.” (Indeed, the “live poultry code” in Schechter Poultry contained restrictions that appeared to target kosher butchers.)

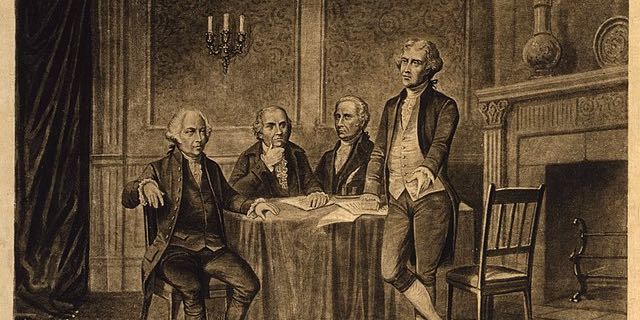

“Would the States conceivably have entered into the Union,” Justice Scalia once asked in a dissent, “if the Constitution itself contained the Court’s holding?” A ruling that endorsed private delegation would surely fail that test. “If one maxim reflected Americans’ ideas of representation,” Jack Rakove proposes in Original Meanings, his Pulitzer-Prize winning book on the drafting of the Constitution, it was the belief, captured in a remark by John Adams, that “a representative assembly ‘should be in miniature an exact portrait of the people at large.’” The colonists rejected “virtual” representation, a concept invoked by the British to defend the prerogatives of an oligarchic Parliament riddled with rotten boroughs. As the eminent historian Gordon Wood puts it: “This notion of being virtually represented struck Americans then, and us today, as absurd.”

Not everyone was convinced of the practicality, or the wisdom, of ceding every choice to the unadulterated enthusiasm of the vox populi. During the debates over ratification, Hamilton complained that “the idea of an actual representation of all classes of the people, by persons of each class, is altogether visionary.” Madison wanted wise representatives to pursue “the true interest of their country,” even when it diverged from the views “pronounced by the people themselves.”

It is probably in the “populist Anti-Federalist calls for the most explicit form of representation possible, and not in Madison’s Federalist No. 10,” Wood opines, where “the real origins of American pluralism and American interest-group politics” are to be found. But in any event, even those who favored a more “filtered” representation wanted what Madison called “proper guardians of the public weal,” and not “advocates and parties to the causes which they determine.” If the Constitution had blessed private lawmaking—to return to Scalia and his test—“the delegates to the Grand Convention would have rushed to the exits.”

Keen to narrow the gulf between the system we have and the system of the Founders’ design, a majority of the justices on the Supreme Court have expressed an interest in strengthening the principle of nondelegation. It is not obvious how far the Court should go—or how far it can get—in using nondelegation to restore limited and accountable government. Ensuring that the power to make laws does not fall into private hands, however, would be a fine first step.