Orwell and the Cancellation of Culture

George Orwell’s appalling vision of the future in 1984 makes clear that totalitarian rule relies heavily on official censorship. Big Brother watches for deviations from Ingsoc ideology and for disloyalty to the Party. While at bottom, thoughtcrimes are political crimes in the novel, the exercise of political thought control inevitably entails the loss of other freedoms apart from political liberty.

Critics of dystopian literature have noted how such works are often less prophecy than they are commentary on deplorable contemporary tendencies. Along these lines, Orwell famously stated that the frightening world he created in 1984 would not “necessarily arrive” but that “totalitarian ideas have taken root in the minds of intellectuals everywhere, and I have tried to draw those ideas out to their logical consequences.”

To help eliminate alternative points of view and troublesome shades of meaning, the Party perpetually reshapes the language into Newspeak, removing words and phrases from the lexicon in order “to narrow the range of thought.” So, in a novel suffused not only with a sense of political terror but with a deep sense of loss, the reader is compelled to think about all the costs of censorship and suppression and the ways in which non-political aspects of life are seized and made political by those who seek power.

Orwell’s championing of free expression, then, extends beyond the political. He argues on behalf of artistic honesty and free speech as inseparable from individual integrity. The establishment of taboo subjects and forbidden forms of expression are demoralizing to all and deforming for writers. Verbal forbidden zones attenuate the culture. This truth is currently being abandoned by many who should be at the forefront of declaring that freedom of expression is the freedom of thought, and that freedom of thought is the ultimate measure of human freedom. Orwell knew better.

“The Prevention of Literature”

In 1946, the same year that he published his most famous essay, the frequently anthologized “Politics and the English Language,” Orwell published another essay entitled “The Prevention of Literature.” Both essays were written while Orwell was in the state of fertile planning implied in Aristotle’s use of the term heuresis, or invention: he was mulling over plans for 1984. Both essays reveal the anxious interest in the political uses and abuses of language that would find their way into that novel, and both show Orwell’s concern with the moral dimensions of language.

Although they tread the same ground broadly speaking, the essays nevertheless differ significantly in their particular emphases. It is the lesser-known, less-discussed “Prevention” that applies most closely and consistently to our cultural state of affairs in 2020. Line after line calls up contemporary parallels. The essay illustrates that it is best to think of Orwell not merely as fighting a brave defense of free political speech, but as advocating positively for free expression in all realms.

“Prevention” warns against the “practical enemies” of free speech, identified as “monopoly and bureaucracy,” but more trenchantly it also highlights Orwell’s antipathy towards the thought leaders who would front the post-war cultural scene. Orwell recognized that the mid-century English intelligentsia and arts world was dominated by an embittered left that was intellectually inconsistent, morally obtuse, and relentlessly negative. Speaking of the left-wing “weekly and monthly papers” of his day, Orwell asserted in “The Lion and the Unicorn” that “there is little in them except the irresponsible carping of people who have never been and never expect to be in a position of power.”

What they might do if given power became clear to Orwell in the 1944 proceedings of the P.E.N. Club, which called a meeting whose professed purpose was to celebrate the tercentenary of Milton’s Areopagitica, a pamphlet expressly written to extol freedom of the press and a touchstone document in the history of free speech. This symposium provoked Orwell into writing “Prevention.” He listened to the P.E.N. speeches, waiting in vain for anything approaching a full-throated defense of unfettered speech. He did hear a defense of the Soviet purges. He did not hear a single speaker quote from Milton’s work. “In its net effect,” he concludes, “the meeting was a demonstration in favor of censorship.”

Plus ça change. Orwell’s analysis of the P.E.N. attendees’ evasions and special pleading predict almost perfectly the response to the Salman Rushdie fatwa, which itself provided a preview of the burgeoning hostility to free expression current amongst today’s woke thought leaders. One would think that fellow writers and progressive intellectuals would have rushed unanimously to defend their fellow artist and to extol the freedom of imagination upon which their livelihoods and their personal integrity depended. But this was far from the case.

Some few mounted a proper defense, but a surprisingly large number of mealy-mouthed, quarter-hearted, yes-but statements found their way into print and onto the airwaves. We heard that Rushdie should have known better; perhaps he even got what was coming to him. Prior to the Rushdie fatwa, the very people making these arguments would surely have claimed with pride never to have stooped to victim-blaming. Nor would they have hesitated for a moment to thumb their noses at Christian taboos in the name of creative transgression, never with the least fear for their lives. Some taboos, however, were suddenly found to be more equal than others.

Most of those committed to silencing others belong to a generation taught to be uniquely vigilant against bullying . . . and yet the tactics used by activists to silence opposing views come straight from the bully playbook.

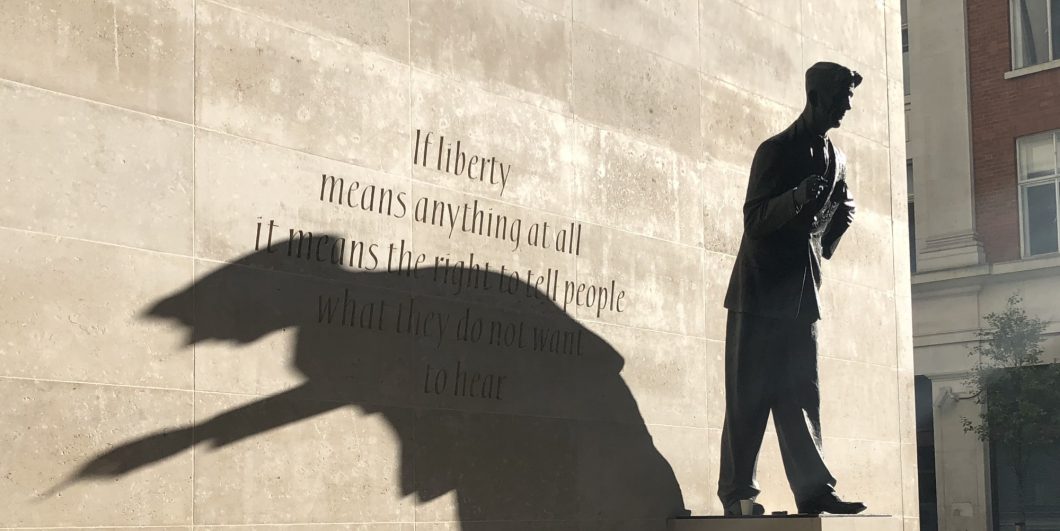

“If it means anything at all,” Orwell avers, freedom of expression “means the freedom to criticize and oppose.” This is precisely what today’s purveyors of cancel culture cannot or will not recognize. One repeatedly reads nakedly self-contradictory statements issued by activists (including, sadly, college faculty and students) who state that, yes, of course they support freedom of speech, while in the same breath justifying their latest (often successful) effort to deplatform, disinvite, or disrupt.

Free speech for me but not for thee has lately found its way into the newsroom, where a younger generation of reporters seeks to create a culture of prior restraint by demanding the suppression of stories and alternative viewpoints (invariably described as harmful) even on the editorial pages. Crossing them can cost one one’s job. There is something woefully lacking in the imagination of these professionals and also in their educations. How is it not evident to them that the powerless have always stood the most to gain from free speech?

The theme of the independent writer daring to ignore the party line is highlighted early in “The Prevention of Literature.” Orwell calls up the lyrics of the Victorian-era Revivalist hymn:

Dare to be a Daniel; Dare to stand alone; Dare to have a purpose firm; Dare to make it known.

“To bring this hymn up to date,” Orwell observes with disgust, “one would have to add a ‘don’t’ at the beginning of each line.”

Unfortunately, adding “don’t” would be sound advice in 2020 for anyone who is required to go along to get along: writers and artists who risk the accusation of cultural appropriation if they step out of the identity lanes narrowly defined for them by progressive cultural watchdogs; employees who run afoul of the company line, not in regard to the company’s products or services, but on selected issues relating to gender identity or affirmative action; university students and faculty who have questions about the de facto party line laid down by their institutions about, say, Black Lives Matter or the exaggerated sex panic “data” used to justify Title IX overreach. Voicing questions about such matters, let alone making objections, can spell professional death.

Art and Appropriation

The direct silencing of opposing thoughts remains easy to detect. Shout-downs, disruptions, calls for muscle, deplatforming, and the rescinding of speaking invitations—all these have become commonplace events recorded in the news, as left-wing activists find ways to suppress alternate points of view. More insidious is the charge of cultural appropriation, a concept that now appears to be an inevitable outcome of multiculturalism as it has been conceived by progressives. Writers and artists are forbidden to engage with topics, themes, styles, or attitudes associated with cultural groups to which they do not belong. It is especially important, the thinking goes, that writers from majority or power-holding cultures steer clear of borrowing from minority or oppressed cultures.

One understands the desire for respect and a fair chance to represent one’s own culture, but cultural practices are not zero-sum entities. They cannot be stolen or exhausted. The real goal of cultural appropriation charges seems to be to induce a permanent cultural cringe, to create a version of cultural crimestop, the Party-induced state of mind in 1984. While some authors have fought back openly (Lionel Shriver is one such Daniel) and some artists don’t seem to pay attention to progressive fads (there are still musicians of various races who openly and happily talk about music’s inevitable borrowing and blending), too many institutions and too many individuals are on board with those who cry cultural appropriation.

It is not unusual to see museums parade their guilty feelings in the guise of admonishments against cultural appropriation. Thus do the benign categories of syncretism, exchange, and cultural hybridization get repackaged as theft. Publishers employ bias and sensitivity review boards, which sift authors’ works with an increasingly fine mesh to turn up hidden offenses. The world of Young Adult publishing is a particular hotspot for high-enforcement identity politics. Narrow definitions of identity have been strictly applied to Young Adult authors, who, upon pain of death by social media, are required exclusively to create characters and stick with themes that conform to their own narrowly defined identity.

Orwell articulated the dangers in self-censorship learned through cultural enforcement. “Even a single taboo,” he writes, “can have an all-round crippling effect upon the mind.” And: “Wherever there is an enforced orthodoxy . . . good writing stops.” It has been observed that those who look to make charges of cultural appropriation often chase away allies. To be sure, this is a just criticism, but if we take Orwell seriously, we realize that the pernicious effects of this concept run even more deeply: “The mere prevalence of certain ideas can spread a kind of poison that makes one subject after another impossible for literary purposes.”

Orwell notes the schizophrenic qualities that attach to obeisance to orthodoxy. In our present age, most of those committed to silencing others belong to a generation taught to be uniquely vigilant against bullying. Schools and the popular culture alike could seem obsessed with fighting against it, and yet the tactics used by activists to silence opposing views come straight from the bully playbook. Likewise with shame, an emotion that progressives would ordinarily declare harmful and retrograde—Down with shame!—Until it is time to whip up a Social Justice Twitter mob to punish someone who has transgressed against the latest progressive orthodoxy. Then it is eternal shame with redemption foreclosed.

We do not live in a totalitarian society, or anything approaching one. Nonetheless, the impulses to power—whether they be purposely disguised or unself-conscious—that impel the heedless Social Justice mindset do present a danger. Habits of mind are more important than the law in determining the lay of the cultural land. The practices now rising towards ascendancy in our most important institutions are already creating a culture of prior restraint. “The Prevention of Literature” analyzes the mind of the ideologue in thrall to orthodoxies that brook no questioning. That makes it an essay for our times.

*Editor’s note: This essay has been updated to correct the term used by Aristotle related to invention.