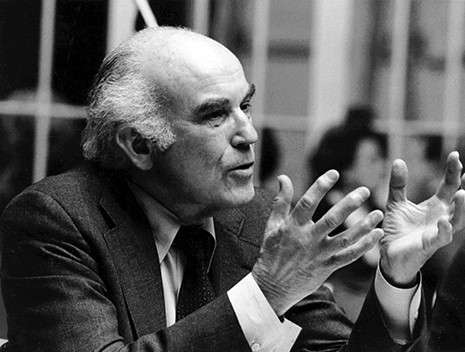

Robert Nisbet, Community Organizer

Richard Reinsch (00:19):

Welcome to Liberty Law Talk. I’m Richard Reinsch. Today we’re talking with Mark Mitchell about the ideas and work of Robert Nisbet. Mark Mitchell is the Dean of Academic Affairs at Patrick Henry College. He teaches in political theory. He’s authored a number of books, The Limits of Liberalism, The Politics of Gratitude, and a book on Michael Polanyi called, Michael Polanyi: The Art of Knowing. He’s also the founder, a co-founder of the webzine Front Porch Republic. As my friend, the late Peter Lawler would say, “He’s a porcher,” and that’s all for the good. Mark Mitchell, thinking about Robert Nisbet, welcome to the program. How did you get interested in Robert Nisbet? Why did you gravitate towards him?

Mark Mitchell (01:06):

The first time I encountered Robert Nisbet was in graduate school at Georgetown. The Quest for Community was assigned to me by a late Dr. George Carey, who was my mentor there, and I think it was a course on conservative thought and he just gave me a pile of books to read and this was one of them.

Richard Reinsch (01:27):

Excellent. Thinking about Nisbet there, when you think about his career and what he had to offer, what did you gravitate towards?

Mark Mitchell (01:34):

Nisbet starts with a psychological insight that human beings are creatures of community. We long to belong. What he worries about is the demise of the kind of associational life. When those dissipate, when we lose the possibility of inclination to affiliate with church, with local organizations and so on, the longing for community doesn’t go away. And the only thing left that seems solid enough, that seems permanent and attractive enough to warrant our allegiance is the national state.

In many respects, Nisbet represents a sort of updated version of Tocqueville’s project that Nisbet brings Tocqueville’s project up into the second half of the 20th century. And in that respect, he provides, I think, a valuable analytical source for helping us to understand our own situation, even though in some respects, our situation has changed since Nisbet passed away in 1996, but in many respects, he understood the trajectories we were on. I think he wouldn’t necessarily be surprised by the situation we find ourselves in now.

Richard Reinsch (02:14):

Yeah. What alarmed Robert Nisbet, what drove him to write the work he’s most famous for, The Quest for Community, which was published in 1953?

Mark Mitchell (02:22):

It was what he understood as the rise of, and total domination of what he called the monolithic state. And what he does is a kind of historic analysis of social and political forces. He points out that in the medieval world, sometimes we mistakenly think that the King for instance, had absolute power and was without rival, but he points out and he does so in ways that are very similar to someone like Bertrand de Jouvenel as well, whose book On Power, I think can be fruitfully read in conjunction with Nisbet, that in the medieval European world, how was it centralized? There were rival centers of power. Surely the King had power, but the nobility is constantly struggling against the King. The church has a kind of political role as well as the spiritual role. What you have is centers of power competing with each other. This has the effect of limiting the power of all. There’s ebbs and flows. But as Montesquieu puts it in his book, and this is something that was influential in the thinking of the American founders, is that the only way to limit power is with rival powers. What happened over the centuries is the nation state, the centralized political national power gained ascendancy, and there’s a complex story there, but that it includes things like the granting of titles of nobility to be commoners, which in effect waters down the power of the nobility while achieving allies in the nobility. In addition, it includes the King doing things like giving grants of largesse, giving goodies to the people as a way of undermining their affection and the relationship with the people, to the nobility. What you have eventually, according to Nisbet, is the consolidation of the national political power and the creation of the people who are isolated, individualized, and those are the two nodes of social existence. It’s very similar to Hobbes’ vision for society, an absolute power and individuals that directly comport themselves vis-a-vis that national power. This creates a power of unimaginable strength, and there’s nothing to compete with it.

Richard Reinsch (05:01):

The Quest for Community, as I was rereading the book in preparation for our interview, what struck me, and I don’t think these were facile comparisons, but how remarkably relevant the book is right now, 70 years, roughly in the future. And obviously it’s not 1953 when he wrote this book. I think he started writing it in 1950. He was in his late thirties. I think it was published when he was 40 years old as a faculty member. He was asking questions about these losses of forms of community underneath the forms of a modern centralized, progressive state. Obviously, World War II had transformed America. The New Deal was in the process still of working through America and making changes. He sort of understands… I think what struck me reading it now is we are community questing, seeking beings. We will have it in one form or the other. And in that respect, one begins to understand sort of mass identification as a strange form of community building.

Mark Mitchell (06:10):

Right? He starts with a psychological insight that human beings are creatures of community. We long to belong. Throughout most of human history, there have been a variety of overlapping complex points of association, family, group and so on. What he worries about is the demise of the kind of associational life. When those dissipate, when we lose the possibility of inclination to affiliate with church, with local organizations and so on, the longing for community doesn’t go away. And the only thing left that seems solid enough, that seems permanent and attractive enough to warrant our allegiance is the national state. So, people that are radically individualized, isolated, and alone are drawn naturally to the national state as a form of community. It becomes what he calls a redemptive community, it takes the role of these other associates. It takes the role of the church, he makes this point several times. With the decline in affiliation or membership with the church, the state steps in as a kind of pseudo redemptive community. There is a kind of religious impulse that lies behind this gravitation towards state affiliation.

Richard Reinsch (07:38):

Rereading The Quest for Community also brought to mind this notion, it isn’t just religion, it isn’t just anthropology. It isn’t just creedal, speaking of Christianity, it isn’t just belief, but it’s the identity, the participation, the concrete reality of religion in people’s lives. He said something similar about the family too, and what local community means to you. If these things are not functional, you don’t see them as a part of making your life whole or concrete or standing it up in any way, you start to retreat from it. It becomes invisible to you. He said underneath modern standardization, centralization, that was undoubtedly the case. How does that hold up?

Mark Mitchell (08:25):

Nisbet’s work is pervaded by a sense of what we’ll need to think about that’s properly human in terms of scale and national community is not properly human being, that’s not the primary locus of belonging. We need to think of neighborhoods and families and parishes that are, exist on a scale that is suitable to our psychological and social needs.

It’s quite true. One of the things that motivates this dynamic is a false understanding of freedom. He knows that in the 19th century there was… He dispositioned to understand freedom as relief, as emancipation, as the extrication of any commitments or relationship from institutions that seem to impose duties or restrictions on freedom. He calls that a false freedom, that freedom is a central part of this discussion that he is having, and what we have is a pseudo freedom that doesn’t satisfy. As a result, we go looking for the very things that we’ve abandoned and because those things have been left behind and in some respects, disintegrated by state power, the only thing left is this national state seeming to hold out its welcoming hands as a source of meaning. And in the other hand, obviously, its social services as goodies that the state offers as kind of an incentive to command loyalty.

Richard Reinsch (09:39):

I think it was the 2016 Democratic National Convention, whatever banners hanging that said, the government is the only thing we all do together. I think in the progressive understanding, that’s quite true. But, Nisbet would have understood the sentiment where that issued from. Thinking of Nisbet on these sorts of losses of forms of community, and I like what you said, because as I was reading him, he talked about words that sort of define an era. The late 19th century we had rationalism, individualism, the notion that one becomes free to the extent you are sort of thrown back on your own resources and you’re not sort of working within a civilizational inheritance of any kind. I mean, that’s clearly the idea of the French Revolution and much of social contract thinking. And he had said, “Well, where has really this has left us.” In the 1950s, he’s seeing, I mean, of course we think of the 1950s and the popular mind as an era of conformity of women not working, of all these sorts of things that we think are wrong. He thinks alienation is defining America and the coming apart of America already.

Mark Mitchell (10:47):

Isn’t that interesting that in the 1950s, the decade that we sometimes tend to look back on as idyllic, that Nisbet is identifying a kind of illness, social illness that he thinks is maybe embryonic in the 1950s, but certainly is growing. We see, I think, the fruits of this today, Nisbet was, as I said, concerned with the decline of church affiliation. He was not, I don’t think, a religious man personally, but he understood the importance of religious form and the social function that the church affiliation had. He predicted, I think, and understood that that outlet, that impulse is going to be satisfied. I think if we look around, we can see a kind of a religious fervor in so much of our politics today. If you think of how identity politics, for instance, seems to be so consumed with the kind of religious fervor to purify and to perfect, this is a religious kind of sentiment and it’s seeking to harness the power of the state to bring about a kind of redemptive outcome. I think Nisbet would not have been surprised at this at all.

Richard Reinsch (12:06):

No, and I was going to raise that point because he has a discussion of communism, which I thought was very provocative. He said, “The doctrines that we are surprised that people would believe in communism when you look at the ideology.” He said, “But we’re missing what it’s really offering many people.” He sort of tracks what Whittaker Chambers, the great anticommunist writer says about communism. Chambers says it gives people a reason to live and a reason to die and I think Nisbet would agree with that. But Nisbet says, “No, it’s community building.” It’s this opportunity of people to do things with other people to enact something, achieve something that matters. And so it’s filling people with hope and a sense of meaning. That’s the power of communism in the West and the reason why, particularly some of our most brightest and sensitive people are attracted to it. As I was reading that, I thought exactly what you were just saying with identity politics. And it also adds, I think it’s not for nothing that this thing really kicks up in the midst of a government imposed lockdown and we have this horrible thing that happens in Minneapolis. Then the next day we wake up and all you hear about is systemic racism and the need to redeem America’s past, or not redeem America’s past, but wipe it away and build something new.

Mark Mitchell (13:22):

I think that’s right. There’s sort of a coalition or a coming together of certain events, including as you say that the George Floyd riots and the coronavirus, that sort of perfect storm of events that all indicate this longing that Nisbet is talking about. A longing that has been misdirected and it’s coming out in ways that are, I think, deeply troubling.

He knows even in a later book called the Twilight of Authority that was published in 1975 and started being the wake of a long protracted war and the recent collapse of a president, things that sound very similar to our situation. He notices that the rise of religious fervor and a kind of irrational religious impulse. I think we’re seeing this certainly on the left, but also on the right. It’s hard to look at what happened January 6th and not see a kind of religious, a cultish impulse that seems to be animating certain facets of the right. Again, this is a longing, it’s kind of bursting out of a longing that is not finding satisfaction in the natural organic associations that are property human beings. I think the term that’s useful here is, even in terms of, or in the relationship to the communist enterprise, to the national socialism or to what we see today is human scale. One of the things that I think Nisbet, he mentioned this term a time or two, but I think it just pervades his work is, we’ll need to think about what’s property human beings in terms of scale and national community is not property human being, that’s not the primary locus of belonging. We need to think of neighborhoods and families and parishes that are, exist on a scale that is suitable to our psychological and social needs.

Richard Reinsch (15:17):

The thinking there too, this irrational, so with the Qanon conspiracy, which was news to me until the last few months. I didn’t really understand what it was doing. Now, I think I have a better handle on it. And apparently some of the people who mobbed the Capitol on January 6th were really fired by this. This drives their thinking and actions. The woman that was shot and died, who was a 14 year air force veteran I read, really did believe in this and was behind her motivation for being there that day, I’ve read. Also thinking previous to that mob was the Jericho Prayer Rally, which I read about, I watched some footage and it seemed to be running Trumpism, America and Christianity together as one thing. It leads you to think there’s, it is something like the concrete forms in people’s life aren’t providing satisfaction, or maybe people have irrational expectations for politics and it’s sort of leading to this, these sorts of outbursts. As I think about that. And I’m looking back to Nisbet. We’ve talked about Nisbet sees these traditional forms falling off, and this has continued to happen. I mean, you think about the 1950s, but as I’m reading this and I’m thinking about family, religion, this was… Most people would say, this is a high watermark for religion in America in terms of participation and attendance certainly. Certainly for Catholicism in America, this is part of the Golden Age. Family life is very sound, at least in terms of divorce rates. Out of wedlock, births are very low and all of these things have sort of changed dramatically as we go forward. Certainly in our day now, I mean, it’s almost abnormal. I think like over 40% of children are born outside of marriage. Marriage rates themselves have declined. I guess these traditional forms seem to increasingly be falling off and being filled by these voids. How would Nisbet, though? Does he offer us any ways to think positively about this and what we might do?

Mark Mitchell (17:24):

At the end of The Quest for Community, he argues that there’s two ways of conceiving the state, the national or monolithic state, and then he would discuss the pluralist state. He argues that what we need is a new laissez-faire, a laissez-faire not of individuals but of community. And he does suggest and argue that the purpose of the state is to support and encourage associational life. Plenty of critics of The Quest for Community have complained that his few pages of solution doesn’t really stack up hopefully, against the 200 plus pages of analysis leading up to the last few pages. But he does try to expand that a little bit in his 1975 book, Twilight of Authority and never left. I think that’s the weak part of his analysis. What do we do? Because even in Twilight of Authority, he notes that it’s sort of a continuation of development of his Quest for Community book. He argues that the attractiveness of the nation state is beginning to wane. And this may, in fact, he’s saying, provide space for the rejuvenation of the kinds of associational life that he thinks is so vital. He even makes a point that the rise of globalization that is helping to undermine the strength of nation states may help to facilitate a new birth of localism. Would that he were right, but when you think of the other kinds of dynamics, for instance, a worldwide war on terror, that’s been going on now for two decades, this helps to embolden the nation state, expand the nation state, a worldwide pandemic. These have not served to undermine the aggressiveness of the nation state, but have actually served to embolden and expand the power of the state. I wish that something like a new age of localism was on the horizon, but I guess I don’t see a lot of reasons, I think.

Richard Reinsch (19:29):

A couple of things there, and I had similar thoughts in thinking about Nisbet’s analysis. It does seem so Brexit, a lot of the political forces that congealed around Trump, challenges to European Union authority, not just in Britain, but other countries. I don’t see in this, that sort of nationalist fervor that Nisbet was scared of, or that Nisbet could have identified. I don’t see that sort of nationalism as an ideology of barrier foes and it becomes us versus them. Parts of that are there, but it seems like currently it actually is a desire to recover this concrete, political reality on behalf of the constituted people or politically constituted people, and that could be a positive development. It could move on from there into various, into damaging ways, but that he actually may have been onto something there. I mean, I think people have looked at aspects of globalism and thought, okay, where does this leave 40, 50% of our population? Another thing that kind of comes to mind, and I think it was a failure. The War on Terror, I think most people just look at that as something of a failure in terms of its global ambition. It achieved something concretely in protecting America from further terrorist attack. But a lot of the other things, it did backfire on America. Certainly, as we look at our forces in Afghanistan, it’s just sort of head scratching. What are we still trying to achieve? I think opinion is coalescing around that. Certainly what we’ve tried to do with China and bring them into some sort of global liberal democratic project has just massively failed. I think leaders in both parties are recognizing that. But, the concrete reaction, or the concrete attempt, one, to implement something like Nisbet’s ideas was the Bush Faith-Based Initiative, George W. Bush’s Faith-Nased Initiative, but that drew all sorts of reactions because it seem to be bringing the government into religion, or into nonprofits and it would weaken those non-profits, a lot of conservatives thought. That’s one way you could see government trying to both relinquish power, but stand new forms of community up.

Mark Mitchell (21:34):

Yeah, I think that’s right. I posed the question or what at least one question is, what is going to happen with the sort of populist resurgence that we saw maybe signaled in 2016. The election of Donald Trump seemed to be an indication of a populist movement, the Brexit seemed to be in an indication of that. Is that carrying into hopeful directions, maybe in some respects. In political terms, one wonders with the domination of the democratic party. How much of say, something like the Green New Deal is going to be implemented, which I think Nisbet would say is a perfect example of kind of religious fervor. We’re going to save the world. There’s a kind of apocalyptic language that the world is going to end if we don’t act aggressively, broadly and faithfully. And this seems to open up tremendous opportunities for the expansion of state power. When you see the kind of aggressive movements that are going to be made and already are being made against systemic racism and patriarchy and all the things that seem to be so deeply infecting our society, so the story goes, this seems to create opportunities for a dramatic expansion of state power and the demise of, or constriction of the freedom of individuals to associate in a kind of pluralistic associational life.

Richard Reinsch (23:04):

As I was thinking and listening to you, there’s something, this aspect of our politics of the Green New Deal, one of the architects of it, if you want to say architect, admitted privately, because I think he was working for Congressman Alexandria Ocasio Cortez, that this was all about, really, this is about using the nation to control people and to bring the economy underneath the control of the government and using this sort of ideological wedge to do it. Another aspect of our politics that sort of drives this is social media and social media obviously, the lifts you out of a place and puts you into various forms of contact with people all over the world, not just in your country, but obviously, people who aren’t, you don’t see them as people as attached as having a life, a biography, a story you’re just put face-to-face or with their avatar, I should say, in some form. How would Nisbet think about social media?

Mark Mitchell (23:53):

He notes the rise in modern world of what he calls pseudo forms of friendship. He’s writing this in 1950s, early 1950s, and pseudo forms of friendship certainly seems to be a pretty good description of Facebook, where we claim to be friends with a variety of people, or we even turn that into a verb, we friend people. But it’s superficial and friendship then becomes something that is disembodied and lacks the thick kind of qualities that constitute genuine friendship. Again, I think he anticipates this, even though he doesn’t see the actual technology. And in so far as some of our social media technology, gives individuals a sort of short term illusion that they are making contact with others, that they belong, that you can belong to a group by liking a post or signing a petition or whatever online. This is, again, a kind of parody of the true kinds of association of life that will satisfy the kinds that Nisbet sees so clearly are necessary for a human life and for thriving. To get this very clear, for him freedom, political freedom thrives in cultural diversity, and this diversity is diversity of association, that the state needs to create the space and opportunities for different people to associate and to express their own proclivities and differences and preferences in a way that’s unimpeded by the state. That doesn’t seem to be the vision that’s being handed down at this point.

Richard Reinsch (25:52):

No. The part of government that would be most able to accomplish that would be the representative branches, Congress, Senate, and then at the state level, the state assemblies. Those are the weakest parts of our government. The executive branch is incredibly strong. We get very excited about presidential elections. I think about the inauguration earlier this week, the pageantry around it, and we don’t have the same sort of muscles all when it comes to legislative government, but that’s where actually you could see deals and compromises happen, and needing to happen in a diverse society, such as ours and the way that Congress can do that versus how an executive really can’t. Certainly a judicial branch that really can’t weigh a lot of different competing voices and decisions, it’s got to come down on one side or the other. That also fires our politics and fires how people engage and negotiate with one another. One of the things, and we’ve been talking about this in a way throughout the interview, what kind of a conservative was Nisbet? As people who are listening to this interview would probably think Nisbet is a social conservative of some kind, but I don’t think that really describes his thought, what do you say?

Mark Mitchell (27:02):

Nisbet notes that Jefferson, for instance, could speak of liberty and of the individual, the freedom of the individual, but he was doing so within a social context, and it was deeply formed by tradition and associations and non-governmental structures so that it’s really one of emphasis and context. When those things are burned away, when the traditions of local traditions and affiliations and local associations are burned away, speaking only about, or primarily about the individual and individual liberty, it looks very different because of the absence of that deep context out of which someone like Jefferson speaks.

No, he’s hard to pigeonhole. He’s a conservative of sorts. I would say he’s very much a Burkian. He quotes Burke a lot and he quotes Tocqueville a lot. If that’s any indication, it kind of gives you a sense of where he’s coming from. He sometimes is called a communitarian, although with the 1990s, the communitarian movement, that really doesn’t, because they tended to be much more favorable to and in-bed with the national government. He’s a decentralist I think in important respects, he’s a localist in important ways. He wants to champion the little platoons that Burke speaks of and thinks that those little platoons, human scale associations, are the lifeblood of a healthy and free society. And in so far as he’s critical of big government, he’s also critical of big industry, big business. He’s sort of skeptical of concentrations of power. I think that made some people on the left gravitate towards him, the critique of giantism in industry and in business. So in that respect, he’s a bridge builder too, I think. There’s something that some on the left can find in Nisbet that is attractive and perhaps in that respect, he can help us to generate a conversation, maybe across some of these very hard lines that have been developed recently.

Richard Reinsch (28:30):

I came across an essay he wrote in 1993 called, “Still Questing,” and he talked a bit about the attraction he had found his writings were having amongst the left. I think some of them have contacted him, but he said he didn’t think it would go anywhere because ultimately being a progressive or being on the left of politics is about using the monopoly arm of government to achieve things, to force things. He didn’t think that would really bear fruit. Certainly, as we think about mass concentrations in business, many are concerned about things that are happening in Silicon Valley and the power of those companies. But of course, if you look at the solution of breaking them up, or it seems to involve also the government having a lot of power as well, over what they do. I think that sort of illustrates maybe the problem that Nisbet would have with a left wing response.

Mark Mitchell (29:23):

Yeah, it’s a vexing problem and it recalls something that Hilaire Belloc said in one of his books, The Restoration of Property, he recognizes and argues that big is the problem, whether it’s political bigness or economic bigness, but concentrations of economic power, he thought has to be broken up. And the only entity that’s capable of bringing that about is the state. He says something rather glibly, I think that, “Well, the state has gotten us into this problem and the state can help us get us out.” But that strikes me as a kind of worrisome expansion of state power for the sake of what might be good end.

Richard Reinsch (30:04):

Well, and certainly, I mean, people have noted. I think Josh Hawley had a bill on Silicon Valley to loosen their control over information, but inherently it would involve the government having a stronger hand over the information that those companies illicit or produce or manipulate and that introduces all sorts of problems. Kind of thinking here also, Nisbet’s book as I was reading it and it asks you the question, what type of conservative was he? One of the things that I noted in my read was he praises Edmund Burke. He praises Tocqueville. He refers to them as sort of the philosophical conservatives, I think, of the 19th century, all of whom are realizing that this sort of rationalist, individualist, emancipated approach to freedom and life don’t really stack up and introduce many more problems. It seems to me that’s, as I think about the type of conservative he is, I’m sort of putting him in with those guys who aren’t… We can call them conservative liberals, people who believe largely in something like rule of law, limited government, markets, but want a ring-fence, I think is the way I think about these guys, want a ring-fence, a lot of other institutions and make sure they aren’t impacted by constant progressive ideas.

Mark Mitchell (31:19):

I think that’s right. He’s a liberal in the way that some of the American founders were and he quotes in Quest for Community, he notes that Jefferson, for instance, could speak of liberty and of the individual, the freedom of the individual, but he was doing so within a social context, and it was deeply formed by tradition and associations and non-governmental structures so that it’s really one of emphasis and context. When those things are burned away, when the traditions of local traditions and affiliations and local associations are burned away, speaking only about, or primarily about the individual and individual liberty, it looks very different because of the absence of that deep context out of which someone like Jefferson speaks.

Richard Reinsch (32:13):

You’ve written extensively and thinking about problems in American life, as we approach our problems with Nisbetian eyes, what do you think are some markers or some ways that we should look at these things?

Mark Mitchell (32:25):

Trying to think about that just in light of all that’s been going on in the last year and I think the answer, if there is one, or at least the start of an answer is something that seems so modest and humble that some might just roll their eyes, but I think Nisbet would agree and that is, look around you and do everything you can to build the local communities of which you’re apart. Pay attention to your neighbors, to your neighborhood, to your church, to your parish, to your local schools, get to know your neighbor. We’ve become so focused on national politics and presidential politics and national or international problems that we’ve lost sight of where life and politics really begins. And that’s at the home. That’s next door. That’s with the things that I think Nisbet would agree with are the things that matter. The things that will ultimately sustain us are the things that are closest to us that often get overlooked in the frenzied rush to save the world.

Richard Reinsch (33:31):

I think that’s well said. Ben Sasse released a statement about the January 6th mob, and he had a line in there, he said, “We people yell at each other on Twitter, but do they even know their neighbors?” I thought that was well said. And I also thought the banning of, or the way Parler was kicked off of the Amazon web servers and then it was removed from the iTunes app store, so basically it goes from being the number one app to it doesn’t exist. And I thought to myself, there was so much hand wringing over this and other moves taken by Silicon Valley companies. I thought, “Well, so what, is it the only way we can communicate. Free speech has not been abolished. There are new ways and forms to communicate.” Then I thought about them like five minutes later that, “No, actually, maybe it is in a certain sense.” And it’s certainly the most powerful form of national political interaction is on these forms of communication. I’m not sure that I have a good answer for that, but what that also means though is, as kind of, as you were saying, we more and more see ourselves in these abstract forms instead of concrete forms.

Mark Mitchell (34:42):

That suggests a good place to start. Is limit or abandon social media and go out and meet your neighbor.

Richard Reinsch (34:50):

Yeah. Yeah. I like that. That’s so that’s how we’ll end, go out and meet your neighbor. Mark Mitchell, thank you so much for your time and discussing the life and work of Robert Nisbet. We appreciate it.

Mark Mitchell (35:01):

It’s been a pleasure speaking with you, Richard.