So hard up are the East Germans that they are willing to sell military hardware to their enemies.

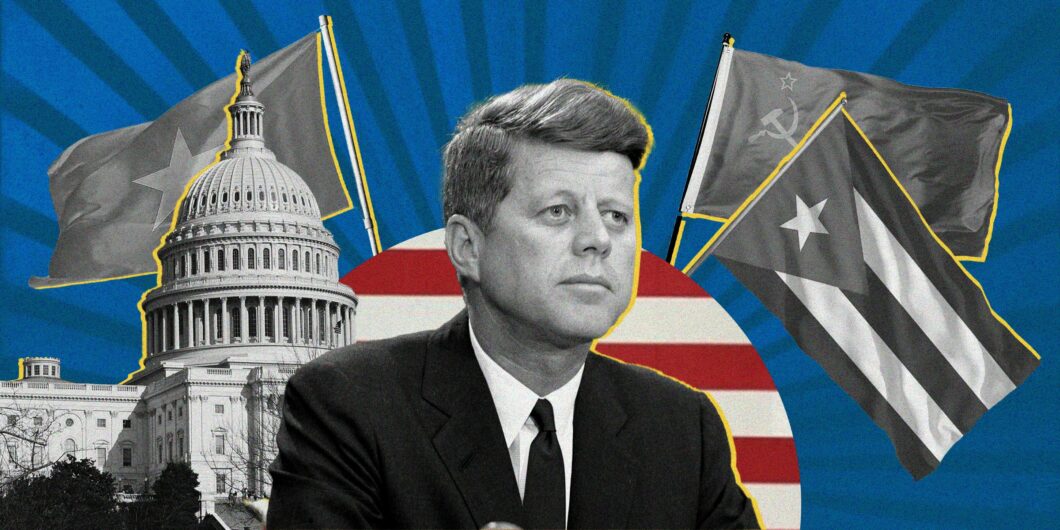

The Kennedy Moment

Stephen F. Knott joins host James Patterson to discuss his recent book, Coming to Terms with John F. Kennedy.

Brian Smith:

Welcome to Liberty Law Talk. This podcast is a production of the online journal, Law & Liberty, and hosted by our staff. Please visit us at lawliberty.org, and thank you for listening.

James Patterson:

Hello. You are listening to Liberty Law Talk, the podcast for Law & Liberty. Today is April 10th, 2023, and my name is James M. Patterson. I’m a contributing editor to Law & Liberty, as well as associate professor and chair of the politics department at Ave Maria University, a fellow at the Center for Religion, Culture and Democracy, and at the Institute for Human Ecology, and president of the Ciceronian Society. My guest today is Dr. Stephen F. Knott. Until his recent retirement, Dr. Knott was a professor of National Security Affairs at the United States Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. Prior to that, Dr. Knott was co-chair of the presidential oral history program at the Miller Center of Public Affairs at the University of Virginia, where I met him and worked for him for a little while. His essays have appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The Christian Science Monitor, The New York Post, Time, Politico, The Hill, oh my goodness, Foreign Policy, The National Interest, I’m exhausted. He is author and editor of ten books dealing with the American presidency, the early republic, and American foreign policy. His most recent book, Coming to Terms with John F. Kennedy, was published by the University Press of Kansas in October 2022, and it will be the subject of today’s interview. Dr. Knott, welcome to Liberty Law Talk.

Stephen Knott:

Well, thank you, James. It’s always great to reconnect with you, and I’m looking forward to our discussion.

James Patterson:

Listeners don’t know this, but I promised to interview Dr. Knott maybe a little while ago. And so if he throws any barbs my way, understand that they’re all very earned on my part. So for those who haven’t read the book yet, one of the things that might surprise the reader is that Coming to Terms with John F. Kennedy has a very strong personal component to it in a way that other scholarly works of yours have avoided. So what is it about Kennedy that makes the subject so personal?

Stephen Knott:

So, James, I grew up in a Kennedy-worshiping family in Massachusetts. And I use that term worshiping with some precision. As far as my mother was concerned, she was of Irish Catholic descent. When John F. Kennedy broke that glass ceiling that had kept Catholic or any non-Protestant out of the White House, from that point on, he could do no wrong. So my earliest memory, believe it or not, is of the Cuban Missile Crisis. So in addition to growing up in a kind of worshipful Kennedy environment, my earliest memories, two of my earliest memories, one is the missile crisis and seeing the fear on my parent’s faces as they listened to President Kennedy in October 1962 talk about the Soviet placement of missiles in Cuba. And then shortly after that, my father came home with plans for a bomb shelter in our backyard. That’s my first memory. My second earliest memory is of the assassination, and my mother sitting in front of this grainy black and white television watching the news from Dallas that President Kennedy had been murdered. So both in terms of my memories and also just in terms of the environment that I grew up in was a rock-solid, New Deal, new frontier family. And my editor suggested, along with some friends that, that personal angle might set this Kennedy book apart from the other 40,000 titles that have been written about President Kennedy.

James Patterson:

Right. It’s a very moving sort of introduction about the context in which you grew up. And I know a lot of … I’m at a Catholic university, and I know a lot of people of a certain age that had that very similar experience. Another thing that I had wondered that made this book a little bit more personal was your previous book to this one, The Lost Soul of the American Presidency, 2019, University of Kansas, or the University Press of Kansas, I always get that wrong. So you had a pretty strongly critical tone of the modern presidency. And so maybe developments in recent history had made you reconsider the legacy of Kennedy after growing up maybe a little bit more critical of him as you describe at the early part of the book.

Stephen Knott:

That’s absolutely right, James. My previous book was critical, is critical of a number of the modern presidents, including President Kennedy, to some extent. And I actually wondered at times if perhaps I was a bit too critical. And I started thinking that way, particularly in light of the Trump presidency, which I viewed as quite destructive. And looking back at least at Kennedy’s rhetoric, one can see a president I think who generally appealed to what Lincoln called the better angels of our nature, who viewed the United States as the last best hope, and belatedly, but nonetheless somewhat firmly tried to move his fellow white citizens in the direction of fulfilling the promises of the Declaration of Independence. So I still remain somewhat critical of Kennedy in terms of his embrace of this progressive notion of a kind of boundless presidency, where the president can be as big a man as he wants to be. I find that’s still very problematic, but I also think that some of Kennedy’s rhetoric did appeal to the best in us. And I thought it was time, after 60-plus years on this planet, for me to revisit my earlier beliefs about President Kennedy, and perhaps come away with a more nuanced understanding of this president and this man.

James Patterson:

As a subject, Kennedy really is a fascinating moment in American politics. It’s at a critical turning point in the Democratic Party. Its coalition is shifting. And Kennedy himself is an Irish Catholic, we talked about that, at a moment when American Catholic culture was really beginning to experience its most popular moment of Notre Dame football, Fulton Sheen, Dorothy Day. So what is it about this moment that Kennedy is capturing that is part of what makes him so successful in winning the nomination and then just barely successful enough to defeat Richard Nixon?

Stephen Knott:

Yeah. I think Kennedy is very much sort of a personification of mid-20th century Catholicism for better or for worse. Again, Kennedy breaks that glass ceiling and makes a very firm commitment to the American people and to his fellow Catholics that he is going to take his guidance from the American Constitution and not from Rome. Now I know there are some folks who believe that Kennedy set far too high a wall of separation between church and state. And to this day, he remains a controversial figure in the minds of a lot of conservative Catholics. But I do see him as a kind of Catholic Irish immigrant success story that a lot of fellow Catholic immigrants really glommed onto, so to speak. And again, in the minds of so many of these folks, he could do no wrong after that point. One of the reasons, James, that I wrote this book is I do see a kind of cultish aspect to the support for John F. Kennedy, and that I find somewhat disturbing in a republic, whether it’s a cultish support for Donald Trump, or Barack Obama, or John F. Kennedy, there’s something troubling about that. But I did witness it up close and personal, and again, particularly for somebody like my mother who had to fight for the establishment of a Catholic Church in a very small New England town dominated by white Anglo-Saxon Protestants. She fought that fight in the late 1940s, and then 10 or 15 years later, there’s a fellow Irish Catholic sitting in the White House. It’s just important for your listeners to understand just how important that was to people of my parent’s generation who were Catholic.

James Patterson:

My mother was at a Catholic school, and I want to say this was when she was in Washington, although it was when she may have been in Hawaii. She was the daughter of a man in the Army, he was a sergeant, and was the only Nixon supporter in her entire Catholic school and received very, very bad marks when writing an essay in favor of Richard Nixon. But the family, my mom’s side of the family is very old Republican, so this of course unpopular at her Catholic school. So let’s get into the meat of the book, which is about the presidency. It’s not a long presidency for very tragic reasons well-known to our audience. But one of the subjects you open with is on the civil rights movement. And I was very excited to read this section because I wanted to know what you had to say, especially because I have read a considerably long book on the same subject by Steven Levingston called Kennedy and King. And I think your reading of Kennedy is much friendlier and sympathetic, given that Kennedy was facing a number of trials at the same time.

Stephen Knott:

That’s absolutely true, James. I do think there’s been a tendency on the part of both the book that you just referred to and many other scholars to be highly critical of Kennedy for what, as one author refers to him as a bystander when it comes to the civil rights movement of the 1960s. There’s definitely an element of truth in that accusation. Kennedy was very cautious at first in terms of his actions as president dealing with civil rights. But I think sometimes folks forget, first of all, just what a narrow victory Kennedy had over Richard Nixon in 1960. And that victory was based in part on carrying some key Southern states, the state of Georgia, for instance, gave Kennedy his second-highest popular vote, just behind Rhode Island. And this is a man who just squeaks into the White House. There’s kind of a cloud surrounding that election, to begin with. And then he’s confronted with powerful barons in Congress from these Southern states, who are rock-solid Democrats, but also rock-solid segregationists. So he does tread very carefully, there’s no question about it. He promised in the 1960 campaign that with the stroke of a pen, he could end discrimination and federally funded housing, and he waits until well over a year and a half to finally do that. But I do think, James, by his third year in office, or by 1963, excuse me, he puts the full weight of his White House behind what will become the Civil Rights Act of 1964. And I would strongly recommend to your listeners that they go onto YouTube and just watch Kennedy’s speech from June of ’63, which was an address to the American public, where he puts civil rights as his top domestic priority, and he cites the Declaration of Independence. He cites the American Constitution. He cites our Judeo-Christian heritage in favor of a vigorous federal effort to finally break down the walls of segregation. And he’ll spend the last four or five months of his presidency lobbying for that civil rights bill. And there’s a reason why he’s in Dallas, Texas, in November of 1963. He’s in trouble in the South. He has alienated a significant portion of the Democratic Party’s base by identifying himself with Dr. King, with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. And I think he deserves credit for belatedly, absolutely true, but belatedly putting the full pressure, if you will, of the White House behind a significant piece of civil rights legislation.

James Patterson:

Yeah, that’s right. He does embrace this language of Judeo-Christianity in precisely the way that Dr. King had, and that element to his speech is picked up and continued through the passage of the ’64 act, in fact. So I was very taken by the treatment you gave of the speech he gives. It was a really good balance, really a correction to a lot of the anti-Kennedy stuff out there, which I have to admit I probably in my own work have been too readily accepting because of my own biases against Kennedy, obviously that I’ve inherited. Another subject that comes up in the book and really gets a finesse treatment given your foreign policy background is a little issue that came up during the Kennedy administration called the Cuban Missile Crisis. What exactly was going on with the Kennedy White House? And why was it that they decided to deal with Cuba, the missile crisis, as well as attempting to stage a coup the way that they did?

Stephen Knott:

Well, James, Kennedy had campaigned in 1960. He took a very hard line on Communism. He’s one of the few mid to late-20th-century Democrats who actually outflanks his Republican opponent on national security. In other words, he comes off as more hawkish than Richard Nixon. And he accuses the Eisenhower Nixon administration of having lost Cuba just as Nixon and some of the Republicans had accused Harry Truman of losing China. So Kennedy beats up his Republican opponents on this issue of Castro coming to power in 1959 during the Eisenhower years. And he suggests that he’s not going to tolerate that. And, of course, you end up with the fiasco at the Bay of Pigs in April of 1961. Now he had inherited a plan from the Eisenhower administration to try to topple the Castro government. We could talk for hours about the differences or the changes that Kennedy made to Eisenhower’s plan. But the bottom line, that thing was just a total disaster. He took full responsibility for it, but he also continued to try to topple that government. And you end up with something called Operation Mongoose, which was a campaign of economic sabotage, but also a campaign involving trying to assassinate Fidel Castro. So this is the lead-up to the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962. That administration–the Kennedy Administration–had been trying to kill Castro for quite a few months prior to that. And, of course, the Soviets and the Cubans were well aware of this. When Khrushchev decides to gamble and put these offensive nuclear weapons in Cuba, I think he thought, Khrushchev thought, that Kennedy was somewhat weak, somewhat vacillating. He had canceled any air strikes for the Bay of Pigs operation. He had stood by while the Berlin Wall went up. And there may have been a calculation on Khrushchev’s part that Kennedy would not respond in a firm manner regarding the missiles in Cuba. Now Kennedy does respond in a firm manner in terms of authorizing a blockade, or a quarantine, I should say, of Cuba. But what we didn’t know at the time was that Kennedy also made some pretty significant concessions to Khrushchev in order to get the Russians to pull those missiles out. And so we secretly agreed to remove the missiles that we have on the Soviet border in Turkey, and also, we agreed to not invade Cuba again like we did in the Bay of Pigs. Those things were kept very quiet, very hush, hush. And one of the interesting things that comes out of the missile crisis, and the reason I can say this with certainty, is we have tape recordings of everything that was said in almost every meeting about the missile crisis. And John F. Kennedy was consistently the most dovish, for lack of a better word, the most determined to avoid a military conflict with the Soviet Union, while demanding the removal of these missiles at the same time. So I give Kennedy considerable credit for a very effective management of that crisis, which was the worst of the Cold War that could’ve easily degenerated into a nuclear conflict between the two superpowers. I do think it’s due to Kennedy’s willingness to put himself in Khrushchev’s shoes, to make some concessions, to demand the removal of the Soviet missiles, but also to allow Khrushchev to save face. And I think we averted World War III by Kennedy so doing.

James Patterson:

Yeah. One of my favorite parts of the discussion on the issue of Cuba was that we focus a lot on the relationship that Kennedy had with Khrushchev. Normally, his presentation is one getting kind of yelled at by Khrushchev hammering his fists and/or footwear on various objects at the United Nations. But really, the part that I was most interested in was how slowly but surely, there’s this sort of emergence of a three-way relationship between Kennedy and Khrushchev and Castro. And Khrushchev’s relationship with Castro eventually helps with the thawing of the relationship with Kennedy because of what Khrushchev’s got with this guy and Cuba, and what he’s demanding Khrushchev do with the missiles. So if you could tell any bit of that story just to tease it up for your future book buyers, I would be very grateful because it’s one of my favorite parts of the book.

Stephen Knott:

Well, thanks, James. I have to say it, I’m glad you sort of highlighted this. I do think there’s a tendency to put almost all of the blame on JFK for the missile crisis. The fact was this was an incredibly reckless gamble on Khrushchev’s part. But more importantly, what emerges from a close examination of the missile crisis is just how zealous, how I would say, dangerous Fidel Castro was. He was furious at Khrushchev and at the Kremlin for the decision to pull those missiles out. Castro wanted this thing to go to the mat. He was itching for a conflict. And some of the statements that Castro made, both publicly and privately, to folks in the Russian hierarchy, really bone-chilling. I mean, look, saying things to the effect, if they want to take us down, we’re going to take them down with us. He didn’t particularly care if the whole world got embroiled in this conflict. So there’s a recklessness about Castro that I think a lot of Western observers to this day still ignore. If you don’t believe me, you can look at the accounts written by Khrushchev’s son, Sergei Khrushchev, in which he talks about some of these really dangerous, irresponsible statements made by Castro at the height of the missile crisis, to the point where it really turned Khrushchev and the Politburo off. They became very concerned about Castro’s stability. And I think that’s a part of the Cuban Missile Crisis that just doesn’t get enough attention.

James Patterson:

In my version of the text, it’s this great part of the book, and pleading for a first strike in the event of an American invasion, Castro told Khrushchev that this was an opportunity to eliminate the chance for the Americans to strike first against the Soviet Union, quote, “An American invasion would be the moment to eliminate such danger,” Castro told the Kremlin, this quote, “Harsh and terrible solution was the only solution, for there is no other.” In Moscow, Khrushchev, the man who once promised to bury the capitalist West, and who had flaunted the possibility of nuclear war during the summit with Kennedy in Vienna of 1961, was astounded by Castro’s proposed final solution, quote, “This is insane. Fidel wants to drag us into the grave with him.”

Stephen Knott:

Absolutely true. And again, not to beat a dead horse, but I’ve often felt that Fidel Castro to this day gets something of a pass from a lot of Western observers who sort of admire the fact that he stood up to the big bully to the north. But there’s an element of Castro’s zealotry to the cause and to his hatred of the United States that is particularly … It’s disturbing in an era of nuclear weapons. And I think he had a kind of cavalier attitude about those weapons that neither Kennedy nor Khrushchev had, thank God.

James Patterson:

It’s sort of like, “Well, if they start a nuclear war with each other, maybe they’ll forget all about me down here.” So this is something of a silly question, but it came to mind when I was reading that quotation. But is it true that Kennedy before imposing the embargo, picked up a bunch of Cuban cigars to keep for himself at the White House?

Stephen Knott:

I believe that is true, James, if my memory serves correctly. I don’t know if I talk about this in the book or not. But I know I’ve come across references to, I believe, somebody in Pierre Salinger’s staff. Salinger was Kennedy’s press secretary, was somehow able to get ahold of these Cubans. Kennedy did like a good cigar, and I think that story is absolutely true.

James Patterson:

Well, I do like a good cigar as well, but I would never violate the embargo. That would be wrong. So Kennedy had an experience of war, and you mentioned earlier that he was dovish on nuclear war. To what extent did his experience serving in the Pacific theater influence his position on conflicts with the Soviet Union or other powers, especially given that this is a period when we’re starting to see the emergence of the problems in Vietnam?

Stephen Knott:

Wow, terrific question, James. I mean, Kennedy’s hatred of war, I think is, an aspect of his persona that is another one of these somewhat unexamined or underappreciated areas. His letters home while he served in the South Pacific during the second world war are filled with anti-war references. Now look, he wanted to defeat the Japanese. I mean, he was a patriot. He wanted the United States to succeed in that war. But he really developed a firm hatred of war. Two of his crew members were killed during that PT-109 incident of August 1943, where Kennedy was the skipper of a PT boat. Two of these young men were killed. One of those young men had talked to Kennedy about having had a dream in which he was killed in the war. And Kennedy notes that this young sailor was sort of obsessed with the idea that he was not going to make it home. Sure enough, he did not make it home. And Kennedy writes in one of his letters his regret that his efforts to get this guy transferred off his boat did not succeed. Now look, there may be a lot of aspects of John F. Kennedy’s character that none of us can find particularly admirable, but in this case, it does strike me that Kennedy had a principled, a deep and abiding objection to war, he had seen it up close and personal. And when he’s president a mere 20 years later, by the way, these are not particularly distant memories. PT-109 was in 1943. He’s in the White House less than 20 years later. And his hatred of war leads him both in the Berlin crisis in the fall of ’61, I would even say at the Bay of Pigs in April of ’61, the missile crisis in ’62. And I would also apply this to Vietnam. I just don’t think John F. Kennedy would’ve gone to the lengths that Lyndon Johnson did in terms of committing over half a million American soldiers to Vietnam. This was a man who hated war, who had seen it up close and personal, who had lost his oldest brother in the war less than a year after the PT-109 incident. So again, this is an aspect of Kennedy’s beliefs that I don’t think is appreciated. And yes, you’re absolutely right, James, it does guide his foreign policy and his national security decisions. And by the way, I would just add to this, there’s a reason why some of the hawks in the defense department at that time, I’m thinking particularly of General Curtis Lemay, who was the Chief of Staff of the Air Force, thought that Kennedy was soft, thought that Kennedy was an appeaser like his father, as a lot of folks liked to say. And you know what, they were onto something. Kennedy hated war, and that guided his decision-making process in the national security arena.

James Patterson:

Reading here in the chapter on Vietnam, Kennedy added that the United States was prepared to consist them, but I don’t think that the war can be won unless the people support the effort. And in my opinion, the last two months, the government has gotten out of touch with the people. Here are the people, I think you mean the Vietnamese people. Kennedy hoped that it would become increasingly obvious to the government that they will take steps to try to bring back popular support for this very essential struggle. He was cautiously optimistic that the South Vietnamese would regain the support of the people with changes in policy and personnel. Absent those changes, the chances of winning would not be very good. Do you think that with the way Kennedy was approaching Vietnam, had he lived, we would’ve had a different experience there?

Stephen Knott:

I do think so, James. And let me start off by saying I’ve gone 180 degrees on this. I used to be firmly in the camp that John F. Kennedy would’ve followed the same course of action or a similar course of action as Lyndon Johnson. I mean, it was Kennedy’s best and the brightest, McNamara, Rostow, Bundy, Rusk, et cetera, who guided Lyndon Johnson into that war. But, after writing this book, after listening to White House tape recordings, and after combing through countless documents, it’s very clear to me that Kennedy was a skeptic about America’s role in Vietnam. Now he broadened it, no question. The number of advisors that went from Eisenhower to Kennedy was pretty striking, I think 700 or 800 perhaps when Eisenhower leaves office, to 17,000 by November of ’63. So that piece of evidence will tend to suggest that Kennedy would’ve escalated. But I think it ignores the fact that throughout the major meetings on the course of the war in Vietnam, Kennedy is one of the most skeptical voices in the room who was constantly pushing back against those folks who were arguing for a greater American role. And let me add this: Kennedy spent a considerable amount of time in so-called French Indochina in the early ’50s as a member of the House Foreign Affairs Committee. And it had quite an impact on him. One of the things I admire about John F. Kennedy, whether as a president or a member of Congress, is he had a tendency to go outside of official channels to gather information. And when he’s in French Indochina, he’s meeting with mid-level officials who aren’t giving him the sort of State Department official diplomatic line. And they are expressing to him their concern that we are moving towards sort of picking up the slack of this French Colonial regime, and that would be a disaster. So he remembered those conversations from 10 years prior when he was a junior member of the House, and again, throughout his presidency, you see repeated skepticism about these optimistic assessments that are coming out of Vietnam. So I’m part of that school of thought that speculates, and I grant you it’s speculation, that had he been reelected in ’64, he somehow would’ve tried to pull off a negotiated settlement in Vietnam, similar to what he and Khrushchev had done in nearby Laos.

James Patterson:

Kennedy’s presidency really is a dramatic test of America’s replacing basically the British Empire as a kind of preserver of trade access on the open seas, and ensuring, at least in most cases, some level of peace among nations. And so you can see how Vietnam, especially with its connections to Communism, would be such a difficult knot to untie. This sort of aspect to governing with Kennedy is very tough to parse out. So I wanted to move to something that’s actually at the beginning of the book. Maybe I should’ve started here, which is that Kennedy’s got this very famous advertiser, at least among political scientists, it’s famous, in which the song is (singing). Do you know what I’m talking about?

Stephen Knott:

I know what you’re talking about.

James Patterson:

Listeners who don’t know, I won’t torture you with my atonal singing. It’s on YouTube. You can listen to it. It’s one of the most vacuous modern advertising ads there is.

Stephen Knott:

No question about it, James. Look, part of the reason why Kennedy manages to win the White House in 1960, even though at the beginning of 1960, he’s still somewhat of an unknown entity, he was not the favorite of party leaders in January 1960. They were looking at Lyndon Johnson. They were looking at perennial candidate Adlai Stevenson. They were looking at Senator Hubert Humphrey or Senator Stuart Symington. Kennedy and his father, who of course had experience in Hollywood, understood the power of public relations, and they took advantage of this new medium of television, which was really catching on by 1960. And you end up with some vacuous things like that ad that you just cited. And of course, you also end up, and this has to be acknowledged, Kennedy and those famous four debates with Vice President Nixon, he just looked good. He came off well on television. Nixon looked kind of pale and sweaty and shifty-eyed. Kennedy had worked on his tan for the previous days leading up to the first debate. Kennedy wore the correct color suit. He knew the importance of imagery. And I understand that as a criticism of JFK. However, where I differ, I think some folks take that a little too far. He was not just good looks, good hair, I’m jealous of the hair, good teeth. There was substance to the man. He had an interest in history. He particularly enjoyed historical biography. He had a very inquisitive mind. He had an ability to think, as we say today, outside of the box. And so where I differ with some of his critics who say that he would be long forgotten were it not for Lee Harvey Oswald, I think that’s patently false, and it’s unfair. This was a man of some substance, in addition to being perfectly suited for this new technology of television.

James Patterson:

Yeah. To that point, there’s a great discussion you have of the experience the Soviets and the Americans have in the testing of a nuclear warhead called Big Ivan, which was terrifying to read. And you conclude when discussing how Kennedy responded to its detonation, such a speech, the speech that he gives in response today would flummox many Americans. And you say this because of the level of detail and attention that Kennedy gives on the subject of nuclear weapons. I wanted to ask you about this because: Do you think that Kennedy was lifting people up and addressing them seriously as the Americans who would be affected by his policies? Or do you think that today people talk down to constituents so that they’re no longer required to think hard about policy decisions?

Stephen Knott:

That’s a really terrific and tough question, James. I mean, I’m inclined to say that Kennedy liked or preferred to talk up. And I’m glad you did cite that passage. And by the way, there are other speeches as well, which I think would probably not work today, simply because they are aimed too high. That is an element of Kennedy that I do admire, he and his speechwriter, Theodore Sorensen. They were wordsmiths of a sort, and they were good writing team. And I do think Kennedy’s rhetoric is some of the more impressive rhetoric in the history of the United States presidency. But yeah, I think today a lot of that speech you mentioned, where in response to the Soviets resuming atmospheric testing, even his missile crisis speech from October ’62. I’m not sure that would work today. We have gone backward I think in terms of the kind of rhetoric that the American people seem to respond to, even reading the transcripts of the Kennedy-Nixon debates. They’re actually fairly highly pitched and they’re quite impressive in that sense. And it’s one of the sad things to see that today in this era of soundbites and social media, the constant back and forth on social media, where people insult one another, part of the reason I wrote that book was to show the American people that there is an alternative, and it’s not that far removed from the present day.

James Patterson:

One of the striking passages towards the end of the book on the subject of Kennedy’s assassination is much of the blame for the proliferation of Kennedy conspiracy theories rests with Lyndon Johnson and his creation of the Warren Commission, which surprised me. Although, I later learned what you meant by that. But Johnson normally gets a lot of credit for using the tragedy of Kennedy’s assassination for pushing through a lot of great domestic agenda reforms, like the Civil Rights Act, but also going to great excess with Vietnam. I had not heard this, although I’m not a great Kennedy scholar, not heard this discussion of Johnson being the person responsible for the conspiracy theory. So why don’t you explain that while I put my tinfoil hat on?

Stephen Knott:

Sure. Let me say right off the bat, James, I’m not a conspiracy … I’m not somebody who’s into these conspiracy theories. I believe that Lee Harvey Oswald killed President Kennedy and most likely acted alone. But what I meant by that statement was that Vice President Johnson, who in some ways as you mentioned, did handle the transition quite skillfully, did put pressure in a sense on what became known as the Warren Commission to point the finger at Lee Harvey Oswald and to remove any speculation that the Soviets, or the Cubans, or both were somehow behind the murder of President Kennedy. Johnson’s concern was that if that was the conclusion, that could spiral out of control, God knows even end up with World War III. Keep in mind, November 22nd is barely a year after, just slightly a year after the Cuban Missile Crisis, so things were still quite tense between the United States and the Soviet Union. And Johnson wants to make sure that this commission comes out, quote, unquote, with the right conclusion. And the right conclusion, according to Johnson was that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone. Now I happen to believe they got it right. But the fact that there was and we now know there was this pressure to come to that conclusion casts a shadow over the verdict in a sense of the Warren Commission.

James Patterson:

I took it off, so no one can hear the foil crinkling. It was just not good for broadcast. But was Kennedy a conservative?

Stephen Knott:

Yeah, that’s a good question. I have made the case to a number of my liberal friends that I don’t think you see a great society with a two-term presidency of John F. Kennedy. Again, it’s speculation, I could be wrong, but I’d like to think it’s informed speculation. I think Kennedy being the son of a businessman, and also not quite the new dealer that Lyndon Johnson was. Lyndon Johnson saw himself as completing the New Deal. That’s not what John F. Kennedy was about. And again, I don’t see the kind of massive great society proposals coming out of a second Kennedy term. Again, partly due to this little bit of a distance between the Kennedy family and the Roosevelt family due to bad blood going back to the second world war, Joseph P. Kennedy, the president’s father, being Roosevelt’s ambassador to England, and then being recalled in somewhat negative circumstances, to say the least. But also again, just the Kennedy coming out of a very different milieu if you will, and he’s not the new dealer, he’s not the worshiper of FDR that Lyndon Johnson was, and I just don’t see the same sort of gut reaction or the gut sympathy for the kind of massive programs that will come to characterize the great society. Let me add to this, by the way of course, conservatives like to point this out, Kennedy’s proposal for a tax cut in 1962, I believe, which does become law, and would later be cited by President Reagan as an example of kind of supply-side economics. Now Reagan may be a little bit off the mark there, but that’s a gesture that I don’t see … It’s not a gesture. That’s a policy that I don’t see Lyndon Johnson pursuing.

James Patterson:

I think I wanted to end this with these broader questions. I shouldn’t have launched you into such a difficult question without any warning. What did Kennedy do to the presidency? I mean, you’re a great scholar of the American presidency, a student of it for many years. What do you see as Kennedy’s legacy? He was not in office that long, but he died very tragically and at a critical moment.

Stephen Knott:

Yeah. He was only president for two years, 10 months, and two days, so that’s a mere blip in the history of this country. But by the way, this goes back to your previous question. I do see John F. Kennedy along with Ronald Reagan, and this again maybe plays into this notion of Kennedy being somewhat conservative. Both of those presidents I think believe in American exceptionalism, which I know is a controversial doctrine these days. But I think of the entire Cold War presidency, those two presidents, Kennedy and Reagan, made the most compelling case for the superiority of the Western world over the totalitarianism of the Soviet Union. And I see Kennedy’s rhetoric, his inaugural address, his American University speech in June of ’63, his civil rights address in June of ’63, and his speech at the Berlin Wall in June of ’63 as some of the most powerful rhetoric in the history of this country, in the history of this presidency, and again, I see all of those speeches as appealing to the better angels of our nature. And in that sense, I see John F. Kennedy as a very positive force, somebody urging his fellow citizens to give something back to their country, to engage in service before self. That’s very positive. The negative side of the equation, the negative impact on the presidency is he is very much a part of this 20th-century progressive view in the president being as big a man as he wants to be. Going back to Woodrow Wilson and Teddy Roosevelt, and of course, Franklin Roosevelt, this kind of unbounded presidency that sort of promised the world to the American people. And I think what that did is set up both the presidency and the federal government writ large for pretty dramatic fall, if you will. It’s simply impossible to deliver on the promises of the 20th-century activist presidency. And Kennedy is very much a part of that, and I acknowledge that forthrightly in the book, and I see that as the most egregious legacy of his when it comes to the American presidency. It’s simply an unsustainable conception of executive power.

James Patterson:

The myth of Camelot that was the sort of way of dealing with the publicity of the Kennedy family as a kind of happy family, and behind the scenes, of course things were not so happy. And Kennedy also had some pretty serious medical problems. But the myth of Camelot after his assassination really did dominate the way that people interpreted Kennedy, as well as the … You mentioned the wordsmiths like Sorensen, very captivating kind of writing style for an audience that wanted to hear lot of the conclusions they were reaching. Feel like that whole world has really come to an end. And it seems like this is a good opportunity to be writing such a book about Kennedy because you no longer have to tussle with the Kennedy industrial complex sort of raining down their official line on anyone who wants to make serious inquiries. Is this a change that you’ve noticed? Am I off-base with this?

Stephen Knott:

Well, you’re very much on target, James. Part of the reason I had drifted away considerably as a younger man, my admiration for John F. Kennedy really began to wane, I even reached the point where I considered myself a Reagan Democrat, and maybe even adopted that belief that he was sort of just good looks, good hair, good teeth, et cetera, telegenic. That’s gone. But you’re right, Camelot is gone. That was a creation of Jacqueline Kenned. Less than a week after her husband was killed, she told the most prominent journalist in the United States that her time in the White House with the president was similar to sort of the hit play, hit musical of the era of Camelot. It lasted for maybe 20 years. It’s long gone. And I say thank God it’s long gone because one of the things I saw when I worked at the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston was this kind of manipulation of history that was very much a part of the family’s attempt to control the image of John F. Kennedy and the entire family. And as much as I was a Kennedy devotee at that time, I was also a devotee of history. And I really disliked the fact that decades after the fact, you have family members exerting veto power over particular authors gaining access to presidential papers at the John F. Kennedy Library. It was very disturbing to see. But that’s gone. Camelot is gone. The family efforts to control history, to control of shape, manipulate President Kennedy’s reputation is gone. And thank God for that. It took far too long, but I think we finally are at the point where we have a more nuanced understanding of this presidency. And hopefully my book will serve to contribute to that deeper understanding.

James Patterson:

It certainly did for me. And that was one of the things that I came away from the book really feeling, which is why I wanted to ask you that before we came to a close because it felt like a kind of post-Camelot book, both because it was a sympathetic reading by a more conservative scholar and not the kind of reading you would expect. So it was a pretty remarkable conclusion to reach by the end. Just as a final question, does Kennedy have anything to teach us today? Is there something about Kennedy’s example? And here I mean in a positive as well as in a negative. Kennedy kind of gets a lot of criticism because of his personal problems. But of course, we had a president recently and is now running again who deals with the same kind of issues. Is there anything about Kennedy’s experience that should teach us as people voting for presidents what to expect, or how to handle their decision?

Stephen Knott:

Well, I would like to think that the Kennedy example provides all Americans, and what I tried to convey in this book is this journey that I’ve been on. I would like to think that after reading this book, that perhaps American citizens will undertake a similar journey. We are kind of locked into our own ideological cocoons, unwilling to sort of look or read about individuals from the past or the present who may disagree with us. John F. Kennedy I think in many ways was one of the least ideological presidents we’ve ever had. Now that doesn’t mean he didn’t have principles. I think he actually did. But he was not an ideologue. He did not view politics as a blood sport. And I think all of us should stop viewing politics as a blood sport. One of Kennedy’s, they weren’t close friends, but they got along tremendously well, was Barry Goldwater. Kennedy and Goldwater talked about going around the country in 1964 and debating each other without any sort of media panel, just the two of them sort of going on a road trip, talking about the issues of the day. John F. Kennedy did not view the opposition as traitors. He did not view, as I keep saying, politics as a blood sport. And hopefully, if we could get back … Not that this was a golden age, not that this was Camelot, it wasn’t by any stretch. But there is I think some lessons to be learned from a more civil type of politics, where people across the aisle could talk to one another in an intelligent fashion and not personalize it, not turning it into some sort of mud-slinging event. We all have something to learn from that lesson, I believe.

James Patterson:

I’m reeling here at the idea of a Kennedy Goldwater traveling band.

Stephen Knott:

Yeah, they talked about it, James.

James Patterson:

Oh, man, what they took from us. Anyway, thank you so much, Dr. Knott, for coming on here, especially for your patience with me. This was a really enlightening book and I hope everyone listening decides to go pick up a copy and read it for themselves.

Stephen Knott:

Thank you very much, James. I really appreciate the discussion we’ve had today. And I look forward to us getting together again. Maybe we can have a cigar, maybe even a Cuban cigar.

James Patterson:

Well, we don’t want to break any rules. I’ll take you up on that. Bye now.

Stephen Knott:

Bye-bye.

Brian Smith:

Thank you for listening to another episode of Liberty Law Talk. Be sure to follow us on Spotify, Apple, or however you get your podcasts.