The signs of a wholesale lurch to the Left by Andrés Manuel López Obrador are not there, at least not yet.

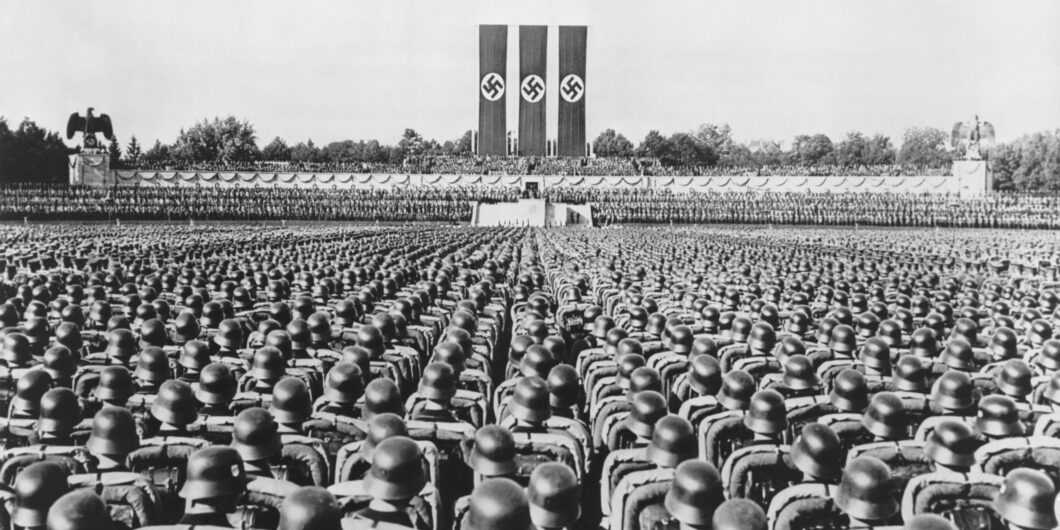

Uncovering Who the Nazis Really Were

Brian Smith:

My name is Brian Smith, and joining me today is Samuel Gregg, a distinguished fellow in political economy at the American Institute for Economic Research. A contributing editor at Law and Liberty, author of numerous books, including most recently, The Next American Economy, which we discussed here on the podcast in October. Sam, thanks for joining me.

Samuel Gregg:

Brian, thanks for having me on. Always good to be with you.

Brian Smith:

So, recently you wrote an essay for us that’s been receiving a great deal of attention. Some of it very surprising from people like Joe Scarborough. The title of this piece is “When a Classical Liberal Confronted Nazi Terror,” and the piece focuses on Wilhem Röpke, a German economist that’s not exactly a household name. And focuses on a speech he gave in February, 1933, warning the German people against embracing the Nazis. Can you give us some background on Röpke and the speech?

Samuel Gregg:

Well, Wilhem Röpke was one of the most important free market economists, certainly in the German-speaking world, and arguably in the 20th century. So he died in 1966, which is quite a while ago. But his life was very much occupied with the… Let’s call it the traumas of the first half of the 20th century. So he was born in Germany. He came from what you’d call an upper middle class background. Very much steeped in medicine, academia, and in his case, the Lutheran Church of Germany. He was born in 1899. He fought in the First World War as a soldier on the western front, very young man, obviously, was a decorated combat veteran. Comes back to Germany, does a doctorate in economics. He becomes the youngest professor in Germany at a very early age in the early 1920s.

And as you know, Germany is obsessed with professorial recognition and the academic world. So when you become a full professor at the age of, I think it was 26, in Germany, that’s kind of a big deal. Now, he was, as I said, a free market economist. He wrote a lot on things like monetary policy, business cycle theory. He was advising the German government in the 1920s on issues ranging from how to deal with the Great Depression, to how to deal with questions of reparations, which, of course, Germany had been subjected to after the First World War. But he was also very difficult to pin politically speaking, because in one sense, he’s clearly a classical liberal as we would understand that today. So he believed in limited government, he believed in constitutionalism, rule of law, a dynamic market economy. And all those things, certainly in Germany at the time in the 1910s and 1920s, were not necessarily the working assumptions of most political thinkers and people involved in politics at this particular period of time.

But at the same time, he, like a lot of other pre-market economists at the time, is very interested in what you might call the cultural, moral, and institutional foundations of free market economies and free societies, in a way that’s, I think, somewhat lacking in our own time. Most economists don’t talk about those sorts of things. So he’s not just a very distinguished economist. He was read everywhere in Europe. He’s also a political economist in the sort of tradition of someone like an Adam Smith.

Now, when it came to German politics, he was extremely concerned by the rise of the hard left, and particularly, of the hard right in the 1920s. And he wasn’t just concerned about them because of their bad economics. He was also concerned about them because he saw these groups as rejecting not just what we would call liberal order or whatever you want to call it, he saw them as rejecting the essence of Western civilization. And so he was, I mean, extremely rarely for a very distinguished academic. He would write in newspapers. He would write for more popular audiences at a time when academics generally didn’t do that.

And so he got very worried in the late 1920s by the rise of the National Socialist Movement. And he saw their rise coming before, I think, a lot of other Germans did. So as early as the 1930s, which is really 1929, 1930s, when the Nazis make their breakthrough into the Reichstag, they’ve become the second biggest party after the social Democrats in the late 1920s in the Reichstag. And Röpke had been warning about these trends for years. And he even in 1930 elections, he actually wrote election pamphlets telling Germans, “Do not vote for these people. They are seriously dangerous. They are not going to moderate their positions when they get into power.” And he also warned Germany’s conservative political and military elites, “Do not get involved with these people, because if you help them get into power, you are going to find yourself more or less co-opted. Which is basically, of course-

Brian Smith:

Exactly. It’s what happened.

Samuel Gregg:

So in 1933, January the 30th, 1933, which was a very recent date, was the 90th anniversary. We just experienced the 90th anniversary of the President Hindenberg, the Great World War I military hero who was president of Germany, inviting Hitler and two other Nazis to become part of the Reich government. Hitler becomes chancellor and two other Nazis enter the cabinet. And the Nazis always viewed this as the day when they effectively seized power. And at the time, there was some concern about this, both domestically and internationally. But even for example, German-Jewish organizations. I mean, they obviously didn’t like the Nazis, but they were not convinced that the Nazis were going to do what Hitler said that they were going to do.

So in eight days after the Nazis took power, Wilhelm Röpke gives a speech, a public lecture in Frankfurt am Main, in which he basically goes through and says, this is how we’ve got to this point. This is how we’ve got to this point where this party that is not just economically not in favor of free markets or any of these things, but actually is representative of a trend in the German-speaking world, and more generally in Europe, to reject what he calls liberalism. And by liberalism, he doesn’t mean sort of 19th century liberalism, as a lot of people understood that at the time. He’s not even talking about the German liberal parties that had, to a certain extent, participated in government in Weimar, Germany in the 1920s. For him, liberalism is another way of saying western civilization.

He’s very clear about this if you read the speech. He is very clear in detailing what he means by this. He means Greece and Rome. He means Jerusalem. He means Judaism and Christianity. He means what you would call broadly speaking natural law ideas. And he also means the particular contributions of the enlightenment. All of which adds up to what he calls Western civilization. And he says the Nazis are in the business of taking this down. And not just the Nazis, but the Bolsheviks as well. Because remember, it’s not just the right that’s been radicalized in this period, it’s also the left. The Communist Party in Germany is very strong at this time, the same time as well. So that is the essence of the speech.

And you think about it, it’s a pretty brave thing to do, because Hitler had made no secret of how he proposed to deal with opponents once he got into power. He’s very clear about this. He says, “I’m going to achieve power by legitimate means,” which is what he did. “But when I get into power, I’m going to dismantle the Weimar Republic.” So to get up eight days after these people have been admitted to power, and very quickly start taking over a lot of state institutions to get up and give a speech like that and say, “I’m telling you now, these people are not just economically problematic. They are a threat to civilization,” in what you might call high German intellectual culture, was a very, very brave thing to do. And he paid a price for that pretty soon afterwards.

Brian Smith:

Which you detail in your piece. And I think one of the interesting things about this is the Nazis were very clear. Hitler was very clear about what they were about. And yet, all over Europe, everyone denied the plain meaning of the words they’re saying, the embrace of the friend-enemy distinction, the virulent desire to murder the Jews, which they were pretty clear about. And yet, all these people, which I do think there’s something about human nature that’s sort of when we think we’re getting what we want politically, we’re willing to for forgive or forget a lot of the sorts of things people, politicians say, as if it’s just politics. But these guys were aiming at something more. And so were the Bolsheviks. What were some of the… Or I guess what was special about Röpke’s understanding that helped him see these threats for what they really were?

Samuel Gregg:

Well, I think there are a number of things. One was that he was very aware of different trends in, let’s call it German nationalist circles. Because the national socialist obviously had their own political program. They had a particularly charismatic leader. But he was pointing to trends in German society that the Nazis had picked up on and amplified in a way that had not really occurred before. So he was very aware that there was a lot of talk in Germany on the right about blood… What you might call blood and soil politics….

Brian Smith:

Or the front experience politics too.

Samuel Gregg:

Right. Right. And he also noticed the rise of this friend-enemy language that was very prevalent on the national circles on the right in Germany, and also on the left as well, one should always add. He also had read the literature that was being put out by these people. Another thing which I think sort of drew Röpke’s attention to the Nazis was that he noticed that students at German universities were embracing many of these ideas. He was very popular as a professor. He was a very good lecturer. He was very accessible to students. But he noticed that more and more young minds in German high intellectual culture, were shifting towards political radicalization. Now, it’s natural for younger people to be a little bit more politically radical than say you or I would be. But he was noticing that these people were moving in this direction very quickly and in a way that was ahead of the rest of German society.

So when he gave his speech at Frankfurt am Main, he was a full professor of economics at the University of Marburg, which the student body was overwhelmingly national socialist in its political sympathies. The city itself had voted by 16 more points for the national socialists considering the national average. So he was immersed and surrounded by these ideas and people like this in the German academic world. Which is where you might think there would be more resistance to some of these ideas. But he was looking at this and saying, “No, this is where these ideas are really flourishing. And part of my responsibility is to speak out against this and warn what is coming.”

Because he said, it’s not just that these people are talking about blood and soil, enemy versus friend logic, et cetera. He said, these people are opposed to reason. They’re opposed to reason itself. They see reason and this sort of the quest for truth. They saw these things as restrictions, as barriers, as things that were impeding the German people from a realizing its glorious destiny, et cetera. So in this speech he says, it’s not just that they’re for all these things. They’re against reason itself. And when a party or a movement speaks in these super Nietzschean terms, very explicitly Nietzschean terms about what their agenda is and how they see the world, then we have something to be severely worried about. And remember, when the Nazis came to power, there were a lot of people who thought, well, they’ll just sort of junk the sort of more radical dimension of their agenda, they’ll accustom themselves to office. They’ll forget all the things they said during the political campaigns. That was not the case. And Röpke saw this coming.

Brian Smith:

Right. And I do think there’s this element of Nazis acquired this particular force because it was an educated… It had the support of this educated young population who really embraced that sort of Nietzschean, vitalist set of currents that were floating around in the 20s. And it’s the sort of commitment that people don’t leave behind. If you really all the way down believe in the politics of the will as these people did over that of reason, there’s no escaping there being deeper consequences over time. So I also wanted to ask you, when you were discussing the defense Röpke laid out of liberalism, the speech. You note he was, “Neither an economic determinist nor a philosophical materialist.” So why did he think rejecting those views were so vitally important to defending an ordered society then and now?

Samuel Gregg:

Well, the first thing to point to make about Röpke in this regard was he was a believing Christian. So he came from a family, as I think I mentioned, of doctors, academics, but also Lutheran pastors. He was a believing Christian. And not every self-described classical liberal at the time was. But he was, as were some of the other German liberals at the time. So he was instantly suspicious of any argument that’s based upon, let’s call it economic determinism or philosophical materialism. So he was basically inoculated against that type of thinking. So that’s the first point.

The second thing is that he’s trying to combat the Marxist interpretation of what was going on in Germany at the time. Because the way that the German communists… And communists in general interpreted the rise of the Nazis, was that this was a type of part of the dialectics of history that were working themselves out. And that the rise of the Nazis was the latest of a series of futile attempts by the capitalist class to resist the inevitable dynamics of history as we move closer to socialism and then communism, et cetera, et cetera. So he’s making it very clear that Germany, what it’s going through, is not some type of Marxist dialectic. He’s saying people are making choices here. They’re not being moved by economic circumstances.

Although, of course, he’s very aware as a distinguished free market economist, that Germany’s problems in the 1920s or particularly the great inflation of 1922-1923, as well as the Great Depression, had steadily radicalized significant sections of the German middle class, and particularly including a lot of academics as it turns out, and younger people as well. So he’s very aware of the economic dimension of this, but he’s saying this can’t be interpreted purely as a type of reaction to or expression of economic circumstances. He says very clearly, look, Germany is in serious economic trouble right now. This great depression is very, very damaging. But the era that we’re entering into is not to be understood purely in economic terms.

This reflects a series of ideas that have acquired popular form, and have acquired a charismatic leader, and a structure that is taking us away from this relatively limited experiment in liberal democracy that the Weimar Republic represented. Now, Röpke was not uncritical of Weimar. Everyone was critical of Weimar to some degree. Everyone across the German political spectrum had some problem with Weimar Germany and its particular way of doing liberal constitutionalism. But that’s not Röpke’s point. Röpke’s point is that we are entering an era in which many of the assumptions upon which things like rule of law, constitutionalism, and Western civilization are built upon are going to be systematically dismantled by a movement and an individual that is very explicit about wanting to achieve these types of ends.

So that’s why he says it’s an end of an era. That’s the title of the lecture, end of an era. The era that’s coming to an end is an era in which this experiment with liberal constitutionalism is going to be junked. And there’s going to be some serious consequences of that among which are the identification of particular groups and individuals, as not being part of what’s called the Volksgemeinschaft, which was a phrase the Nazis used all the time, which meant racial community, the racial community. And that obviously excludes the Jewish people, right?

Brian Smith:

Yeah.

Samuel Gregg:

That’s part of the whole Nazi logic of the idea of race. But it also means the obliteration of the individual. There is no individual in the Volksgemeinschaft. There is the people’s community, the racial community as the Nazis talked about. And when you move into a situation where you start talking that way and thinking that way, it’s not that just that particular groups, who by definition according to the Nazis definition, can’t fit that category, who will be expelled, so to speak, from the body politic. It’s of any concern for individual freedom, the dignity of the person, and anything that suggests that there is a world outside the Volksgemeinschaft that needs to be taken seriously.

Brian Smith:

So there’s the first step in all of this. To go back to the question that I asked, which is when you reduce the human person to these supposedly objective categories or classifications as both the communists and the Nazis were doing, you make it impossible to actually do politics that defends human life in an individual way. Which, of course, was the goal of both of these groups.

Samuel Gregg:

Yes. And-

Brian Smith:

And they want to erase the individual.

Samuel Gregg:

Right. So the Nazis are talking about the group as in the race. The Bolsheviks are talking about the class, and everyone belongs to a class and no one exists outside of class, and everything needs to be defined in terms of the class group that you belong to. So when you think about it that way, the individual, as an individual being, gets pushed out of the picture very, very quickly. And it also means that you are prepared to establish and promote political arrangements in which the individual can be treated primarily as an object rather than as a being that possesses an inestimable dignity of its own.

So neither the Nazis nor the Bolsheviks had any time for notions of individual dignity. They had no time for arguments like you may not use people as a means to an end. You may never instrumentalize people. And Röpke talks about this in the speech. He says, the Nazis will do this. They will use people as means to an end. And when you enter into that type of logic, then killing people, imprisoning people, lying to people, manipulating people, all becomes part of the way that politics is operating in that given set of circumstances. So when you think about it that way, you can see that Röpke is saying the individual is going to be obliterated legally, politically, and even socially up to a certain extent in the new era in which the national socialists are going to take this country.

Brian Smith:

So I think that sums up what makes this so important, why he was so brave for doing this. Because this is a tremendous challenge to what the Nazis were doing. I wanted to conclude by talking about what lessons you think this speech and Röpke’s ideas more generally offer us today. How ought we, if we’re using him to reinforce our own thoughts or help ourselves understand our present moment?

Samuel Gregg:

Well, there’s lots of different implications that can be drawn from Röpke’s speech. And the fact I think that my article got picked up, and tweeted, and circulated by people on the right. But also interestingly enough, as you say on the left, which is not usually what happens to articles that I write, I think people picked up some of the implications that, I think, flow from Röpke’s speech and the way I tried to present it and explain its context to Lauren Liberty readers.

So what are some of the lessons? One is that populism is something that we need to be wary of. Now, by populism, I don’t mean democracy. I don’t mean people expressing their views, or majority rule, or anything like that. What I’m talking about by populism in this context, is when reason is pushed out of the picture for political debate and discussion. And by reason, I just don’t mean empirical reason, I mean reason in the sort of broader, deeper sense that people like Aristotle, or Aquinas, or the American founders for that matter, the way that they talked about reason. Reason is the central means by which we do politics. And there are forms of populism that denigrate that, and even see that as weak. And that’s one thing.

The second thing I would say that comes out from Röpke’s speech is if you don’t ground… Let’s call them liberal institutions, constitutionalism. Rule of law, certain conception of rights, et cetera. If you don’t ground these things on a particularly rich understanding of the human individual person, then you run into problems when people want to demolish these types of institutions. Because if it’s all just based on utility or just based on efficiency, those things turn out not to be particularly strong when confronted with people and movements that are determined to sweep those things aside.

Brian Smith:

Right.

Samuel Gregg:

Third implication, I think, is that Röpke was very conscious of this friends-enemy language that was floating around the German Eastern intellectual sphere, so to speak, at this particular period of time. And this language was very much eventually associated with people like Carl Schmitt, who was a German conservative philosopher, who initially, before the Nazis came to power, had reservations about the Nazis, but became an apologist for the regime, and used this friend-enemy language. And even wrote pieces justifying things like Hitler’s clearly unconstitutional actions in 1934 following The Night of the Long Knives, which is when he basically engaged in terroristic action against the left wing, the hard left wing of the Nazi Party in order to consolidate his own rule. So Schmitt wrote a defense of all this, right?

Brian Smith:

Yeah.

Samuel Gregg:

And that friends-enemy language, once it starts to enter into the political mainstream, it becomes very, very difficult not to start viewing people as threats to the republic, or to see people as groups that you have to push aside and marginalize rather than engage in the very difficult, and complicated, and sometimes frustrating everyday business of politics that exists in a constitutional republic like the United States.

Now, I’m not saying that different groups in individuals who act this way or seem to be acting this way are Nazis. That’s not what I’m saying. I don’t think they’re Nazis or anything like that. I don’t think they’re fascists or anything like that. But what I was pointing to in the article was that there’s a certain logic. Once you start embracing a certain logic of politics… And this is what Röpke’s point was. Once you start embracing a certain logic or politics, then your concern for the freedom of others, the dignity of others, and even things like the workings of the judicial system in terms of upholding constitutionalism and rule of law, once this type of logic gets into the political mainstream, respect for those basic institutions, and procedures, and moral habits associated with the workings of constitutional republic like the United States tend to be put on a secondary level, which I think is highly problematic.

Last thing I’ll say is that Röpke is very aware that liberalism, as he understood it, is not just a 19th century thing, that its roots are much deeper. They go back to the classical world, the Roman world, the Jewish world, the medieval world, the enlightenment world, and that this is where, he believes what he calls liberalism, must root itself. It’s not enough to root liberalism in this sense in economic efficiency, or utility, or just mere procedural. He says it’s got to have these deeper roots if it’s going to survive. And when people start attacking those roots, whether they’re coming from the right or the left, institutions of limited government, rule of law, a market economy, private property rights, and ideas like the dignity of the individual, start to lack the nourishing roots that they need, if they’re going to function and prosper over the long term.

Brian Smith:

Well, I think that’s a great place to end. Thank you very much for coming on the show, Sam.

Samuel Gregg:

Thank you, Brian. Always good to be with you.

Brian Smith:

So you can, if you’re intrigued by this, read far more about Röpke in some of Sam’s other essays on Röpke on Law and Liberty. You can also read more about him in his book The Next American Economy, which I encourage you all to pick up and read. Thank you. Have a good day.