Princeton has been expending considerable energy on what to do about the campus statue of its sixth president, John Witherspoon.

Princeton and the Black Classical Tradition

Several weeks ago, the Princeton Classics Department announced that it was doing away with the language requirements needed to enter its most rigorous program, and my Facebook page and Twitter feed exploded with comment.

I’ll admit it—I belong to the lunatic fringe of the academic world that cares about the study of Greek and Latin literature in the original languages. My Facebook friends were about evenly divided between those who saw Princeton’s move as the End of Civilization as We Know It—arrival time continually updated—and those who saw it as a minor administrative adjustment that would bring us closer to a just world.

If you are surprised by the second view, you need to know the context. In response to the outburst of white innocence-signaling (as Josh Mitchell calls it) unleashed by the death of George Floyd last summer, Princeton, joining the stampede, urged its various departments to consider redesigning their programs to make them more accessible to minorities. The Classics faculty duly climbed Mount Sinai and brought down new commandments. Students will no longer be required to know Latin and Greek before taking courses in Latin and Greek literature. Students can decide for themselves, if the course happens to teach texts in the original languages, whether their presence is appropriate. The change, in the smooth tongue of the committee report, was described as a “move to a flexible language requirement.” It’s assumed that having to know what an ablative absolute is is a “deterrent” to studying Classics. Every cliché of the modern educationalist was wheeled out to disguise the fact that standards were being lowered: More choice! Tailored programs! Students chart their own paths! Diversity! Inclusion! We’re interdisciplinary! We’re rigorous!

The department’s defenders in various op-eds and letters pointed out that the discussion was nothing new, and the revised policy was really just a slight added push in a direction they had already been going. This is true. Since I was a classics major at Duke in the 1970s and later as a graduate student at Columbia, I had been listening to heated arguments about the decline in classics enrollments. One party would say that classics departments could save themselves by teaching “classical studies,” courses about the classical world that required no Latin or Greek. The other party, the one I sympathized with, said that people with degrees in Classics from elite schools should know Latin and Greek, period. French and German departments don’t excuse students from learning French and German (at least not yet). We don’t need fake classics to go along with fake news and everything else that is fake and fraudulent in American life.

The novel element in the Princeton case, at least to me, was the claim that doing away with language requirements in classics was a way of fighting racism and white supremacy. Aha! So that wily old “classical studies” faction has added anti-racism to its former market-driven arguments about maximizing enrollments. The tone of those who defended the new policy was also different: it now seemed a little bit, well, paternalistic. Language requirements were described as “barriers” that prevented “those from underprivileged backgrounds” from “accessing classics.” “The world of classical scholars is one where the white and wealthy have historically prevailed—at least in the absence of changes such as these. This curricular change seeks to open the gates to students who will add new and important perspectives to the field.” Ah, so it’s diversity then. The only way we can get “diverse” voices into our classrooms is to lower standards. Requiring students to master classical languages gave unfair advantages to privileged students from mostly white prep schools, who are already “over-represented” at Princeton. The “Classics” track which required students to know classical languages “functioned mainly as a class segregation tool.”

I noticed that the Princeton Classics Department did not boast any American-born blacks among its members. That made me wonder whether it had paid attention to the outcry back in April over the shuttering of the Classics Department at Howard University, the oldest historically-black university in the country and the only one with a Classics department. I had, for complicated personal reasons. From the coverage, I was pretty sure that black classics students and faculty would take a different view of Princeton’s decision to remove “barriers” to their studying classical languages. I decided to find out. I emailed my friend Jeremy Tate, founder of the Classical Learning Test, who knows everything about the exploding movement for “classical education” in American high schools. He put me in touch with Dr. Anika Prather.

Dr. Prather is a leading expert on the black classical tradition in America. She wrote a doctoral thesis on that subject which was published as a book. She is also an activist for classical education and a remarkable woman generally. Many black people who are involved with the classical education movement are Christian conservatives. Anika (pronounced, she insists, AnEEEEEka) is a Christian but hardly a conservative. It’s hard to pigeonhole her. She is sympathetic to the Black Lives Matter movement but underlines that she is not talking about the organization, with which she has her differences. She speaks movingly of her own fear for “the men in her life,” her brother, husband, and son—law-abiding, Christian men who have all been stopped multiple times by the police. She is grateful for the success BLM has had in making the unfairness of the justice system an issue that can no longer be ignored. She loves “our dear, dear, dear Kamala Harris,” whom she sees as a black person who has risen by education. She laughs about how she likes to dress “really black” when addressing white people, with her dreads, dashiki, and “black girl’s rock earrings,” just to make them a bit uncomfortable. But she is not a person who thrives on confrontation. She has a deep desire for “racial healing” and believes that a classical education can play a role in achieving that objective. Being a Christian educator who loves Jesus puts her in touch with white and black conservatives too, directly and via social media, and she can—sometimes—see things from their point of view.

Being able to read classical languages for yourself gets you past the filters of white translators and white scholarship. It lets you come to your own judgements about the classical world.

It helps that she is a naturally friendly and likable person. When I spoke with her last week over Zoom, along with some faculty and a student from Washington Latin Public Charter School—a racially mixed middle and high school in the District of Columbia—I was impressed by her passion for the classics. All these educators love the classics. At a basic level, they believe that study of Latin and Greek (Washington Latin, remarkably, offers three years of Greek) improves enormously their students’ vocabulary and language skills. It teaches them how to think, write, and speak with precision and power. Speaking is particularly important. They remember how black men like Frederick Douglass and W.E.B. DuBois learned to persuade white men and their fellow blacks by studying classical oratory and classical texts.

The content of the classics is vital too. Being able to read classical languages for yourself gets you past the filters of white translators and white scholarship. It lets you come to your own judgements about the classical world. “Woke” classicists today like to accuse their own field of racism and white supremacy, but for many black educators, study of the classics is a place of empowerment. They like the idea that classics has historically been the preserve of rich white folk. To enter that world and join the conversation as full members, trading future perfect subjunctives with the best of them, is exhilarating. It’s a way of challenging whites on their own turf, of joining their most exclusive club, escaping the low expectations that whites have of blacks—and which all too often they have of themselves. They haven’t forgotten how white educators in the early 20th century tried to discourage blacks from studying classical languages—which would have put them on a par with whites—and promoted vocational studies for them instead.

So it’s natural that activists like Anika Prather, who has started her own private classical school for black children, and educators that teach Latin in charter schools serving minorities, see Princeton’s lowering of standards in a far different light from the one cast by the glow of self-approval among elite classicists. Already discouraged by the losing fight to keep classics at Howard, they see Princeton’s “reform” as yet another blow for the cause of black classical education. To loosen language requirements so that more African-American students will feel “comfortable” shows a lack of respect for black potential. It implies that black students and the teachers that train them are incapable of leaping over the “barriers” that separate them from the highest achievement. Once again, “diversity and inclusion,” that seemingly harmless slogan of progressive educators, reveals itself as a cover for the soft bigotry of low expectations.

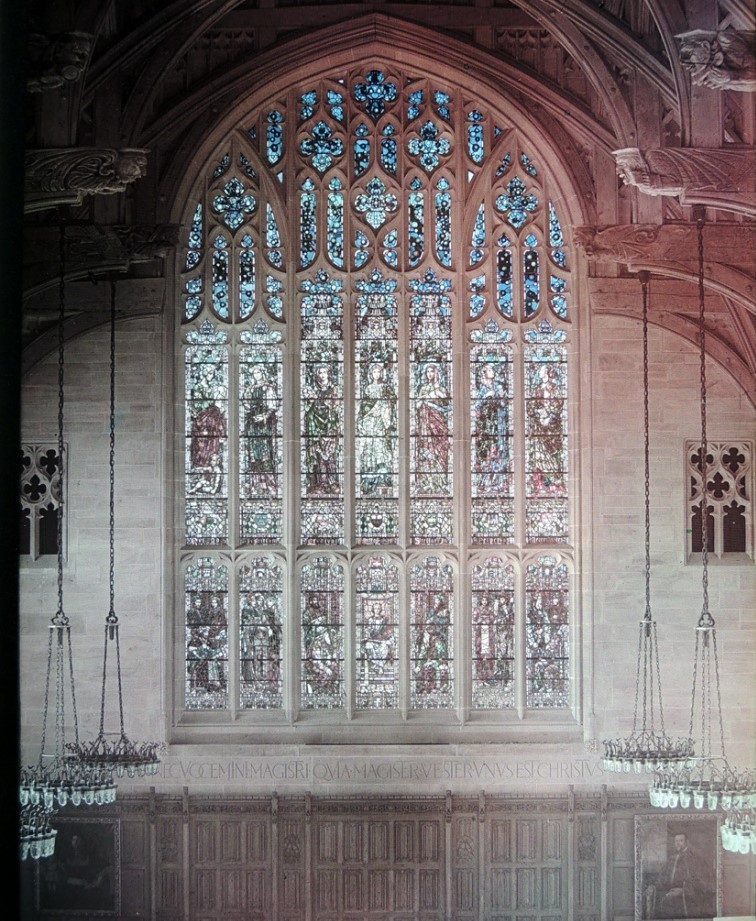

Perhaps Princeton Classics would have been better served in its desire to be inclusive if the university had put more effort into recruiting the best young black scholars from places like Washington Latin or Philadelphia Boys Latin—another excellent charter school that teaches the classical languages to a high standard. One of the most impressive spaces in Princeton is the grand dining room in Procter Hall, with its great stained glass window inspired by the Cathedral of Chartres, illustrating the concord between classical learning and the Christian tradition. It is studded with Latin phrases. If Princeton would only encourage it, perhaps someday there will be more African-Americans who can enter Procter Hall and read the most prominent of those Latin inscriptions, NEC VOCEMINI MAGISTRI QUIA MAGISTER VESTER UNUS EST CHRISTUS.

They can smile to themselves, and say: “I know what that means, and where it comes from”—“And be ye not called masters, for one is your master, even Christ.” (Matthew 23:10).