Balanced budgets and free trade really do help nations to prosper.

Recognizing the Humanity of the Worker

In 1912, Frederick Winslow Taylor, “the father of scientific management,” whom management guru Peter Drucker dubbed “the first man in recorded history who deemed work deserving of systematic observation and study,” was testifying before a US Congressional Committee formed to “Investigate Taylor and Other Systems of Shop Management.” Taylor was explaining to the committee how he had arrived at 21.5 pounds as the optimal shovel load—that is, why a worker could move the largest pile of coal if his shovel held neither more nor less than this weight. To which one of the committee members responded: “You have told us the effect on the pile. What about the effect on the man?”

Herein lies a telling blind spot in Taylor’s perspective on “scientific management.” Taylor argued against the venerable notion that each worker can best determine his own way of working, claiming instead that this responsibility lies with the white collars. So long as workers themselves set the standard, Taylor held, variation and the inefficiency it entails would inevitably rule the day. To organize work scientifically, by contrast, requires enforcement of a standard or best way of doing it, including not only the size of the shovel but each of the motions involved in shoveling:

It is only through enforced standardization of methods, enforced adoption of the best implements and working conditions, and enforced cooperation that this faster work can be assured. And the duty of enforcing the adoption of standards and enforcing this cooperation rests with the management alone.

Taylor, who operated with clipboards and stopwatches, focused on reducing as much as possible the amount of time necessary to complete a task to maximize efficiency. In other words, he focused on the work, not the worker, often speaking of the latter as little more than a tool necessary to complete the task. His low regard for the intelligence and intrinsic motivation of laborers could lead him to adopt unflattering, disrespectful, and even dehumanizing terms. Consider, for example, his description of a man fit for the regular work of a pig iron handler, who must be:

so stupid and so phlegmatic that he more nearly resembles in his mental make-up the ox than any other type. The man who is mentally alert and intelligent is for this very reason entirely unsuited to what would, for him, be the grinding monotony of work of this character.

Enter Lillian Gilbreth, who with her husband Frank rivaled Taylor as a systematic investigator of work and its enhancement. Gilbreth and Taylor could hardly have represented a starker contrast. Taylor, who was born in 1856 in Philadelphia, eschewed admission to Harvard College and instead went to work as a machinist, working his way up his firm’s ranks to chief engineer. After studying many workers in action, he reached the conclusion that they were producing at far less than full capacity and thereby driving up labor costs. He soon developed his principles of scientific management and became one of the world’s first management consultants, building a fortune before his death at 59 in 1915.

Lillian Gilbreth was born to a large family in Oakland, California in 1878. Despite a brilliant high school career, her father opposed higher education for his daughters but eventually agreed to allow her to attend the University of California, Berkeley, where she performed so well that she became the first woman to deliver the commencement address. She began doctoral studies there, but then met construction company owner Frank Gilbreth, moving to New York after they married in 1904. She completed the doctoral requirements at Berkeley but was denied the degree because she was not living in California. Instead, she entered a doctoral program at Brown, earning her PhD in psychology in 1915.

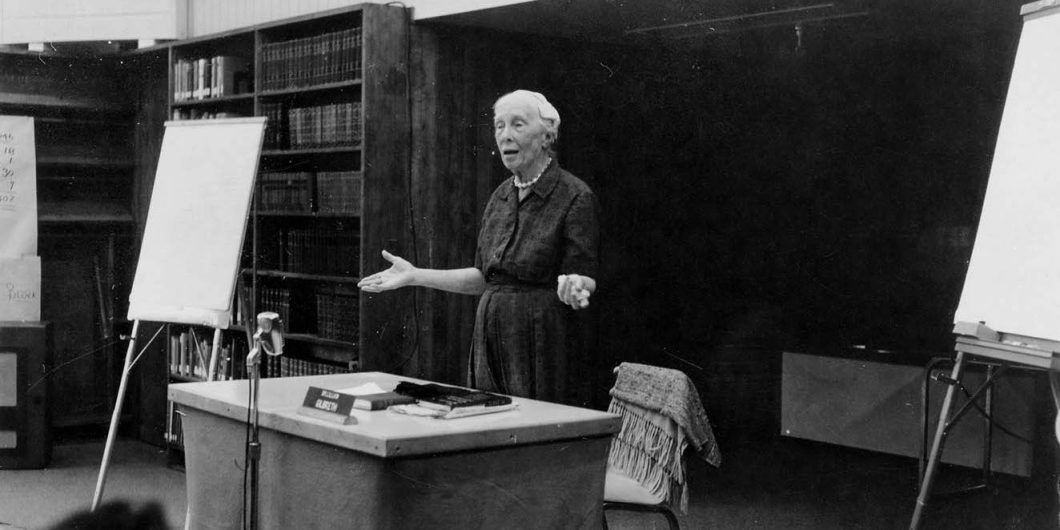

Meanwhile, Lillian and Frank were producing children at a rate of about one every 15 months. One was stillborn after an accident and another died at age 5, but the remaining 11 survived and all graduated from college. Two of their children later wrote the 1948 book, Cheaper by the Dozen, which was turned into a Hollywood film in 1950. As their family burgeoned, Frank and Lillian operated a business consulting firm, producing numerous books and journal articles and lecturing throughout the United States and Europe. They pioneered the use of photographic equipment in time-motion studies, establishing the forerunner of contemporary ergonomics. Frank died suddenly in 1924, leaving Lillian to carry on alone.

Lillian soon found that many formerly loyal consulting clients did not want to do business with a company run by a woman, so she reinvented herself as a consultant to firms whose employees or customers were predominantly women. She became an early expert in the field of home economics, applying scientific principles to household tasks. Her many innovations in this sphere included the so-called triangle kitchen, the foot-pedal operated trash can, wall-mounted light switches, and the inclusion of shelving in refrigerator doors. She also researched menstrual products, surveying over 1,000 women to aid a client in developing a better sanitary napkin.

Where Taylor treated work and workers as machine-like mechanical processes, Gilbreth regarded workers as human beings. She focused less on efficiency and more on fatigue, seeking to enable workers—whether in the factory or in the kitchen—to complete tasks with as little exhaustion as possible. This would make work less taxing, free up more time for leisure, and enable workers to approach recreation with more energy. Where Taylor wanted to boost profits, Gilbreth sought to reduce what she called “humanity’s greatest unnecessary waste,” the expenditure of needless time and energy on a task that could be completed with less mental and physical strain.

Taylor’s purely behaviorist approach rendered the worker a mere tool, where Gilbreth saw a collaborator, a neighbor, and potentially even a friend.

This focus on the experience of work from the worker’s perspective earned Gilbreth the title of the first industrial psychologist. And she applied this approach not only to manual labor but to education, where she sought to enable both teachers and students to impart and receive knowledge with as little unnecessary expenditure of energy as possible. She wrote, “It is well recognized that the teacher must understand the working of the mind in order best to impart information in a way that will enable the student to grasp it most readily.” And she recognized that, far from being confined to the academy, this educational mission applied to all spheres of life, since “almost every man is a teacher.”

In many respects, Taylor’s version of scientific management might have applied just as well to robots as to people. But Gilbreth focused on the psychology of the worker, an interest even more natural to her than her husband, whom she describes in this passage:

The things which concerned him more than anything else were the what and the why—the what because he felt it was necessary to know absolutely what you were questioning and what you were doing or what concerned you, and then the why, the depth type of thinking which showed you the reason for doing the thing and would perhaps indicate clearly whether you should maintain what was being done or should change what was being done.

Thanks to Gilbreth, workers would be treated not as cogs in a machine, but as people. So great was her compassion for workers that she devoted much of her career to improving the work and home life of persons with disabilities, a population that had exploded as a result of World War I injuries. This required, for example, studying special challenges faced by the blind in performing routine tasks, developing curriculum for teachers of the blind, teaching the blind themselves, and finding opportunities for the employment of the blind in industry. Taylor might have branded such workers inherently inferior, but Gilbreth concentrated on enhancing their capabilities to contribute.

This concern for the worker as a human being instead of an economic tool expressed itself in many practical forms. With Frank, she improved lighting conditions for workers, thus reducing eye strain, and introduced regular breaks throughout the workday. She installed suggestion boxes in the workplace, so the voices of workers would be heard. She required employment contracts to be signed by representatives of both management and organized labor. And when she became the first woman engineering professor (1935) and later the first woman to be promoted to full professor at Purdue University (1940), she focused her considerable energy on opening up careers for women.

In 1966, Gilbreth became the only woman to receive the annual Hoover Medal, awarded jointly by five engineering societies for “outstanding extra-career services by engineers to humanity.” She was lauded for her “recognition of the principle that management engineering and human relations are intertwined,” and “her unselfish application of energy and creative efforts in modifying industrial and home environments for the handicapped,” resulting in “full employment of their capabilities and elevation of their self-esteem.” For Taylor, a laborer was defined by strong limbs, but Gilbreth peered more deeply into the lives of amputees, recognizing the deep connection between work and life fulfillment.

As even a cursory familiarity with Gilbreth’s story makes abundantly clear, she was no stranger to or adversary of hard work. Although Taylor talked more about efficiency, productivity, and profit, Gilbreth also well understood their importance. What made her approach different and more enduring was her focus on workers. To get people to do better work, she recognized, it is necessary to give them good work to do and treat them well as they do it. Taylor’s purely behaviorist approach rendered the worker a mere tool, where Gilbreth saw a collaborator, a neighbor, and potentially even a friend.