Redeeming the Constitution

Is there a “better” way to do originalism? Professor David Forte does not seem to think so, at least not in the way Hadley Arkes and company recently proposed. Presenting a “better” originalism, Arkes, Josh Hammer, Matthew Peterson, and Garrett Snedeker put forward an originalism that honors the Founders through an unwavering commitment to natural law principles. Though Professor Forte praises the authors for reminding us of our natural law commitments, he does not abandon the old “originalist” ship. Rather, Forte calls our attention to the “correct” originalism, which incorporates all three elements of law: natural, positive, and prudential. Arkes’ version may respect the natural and positive elements of law, but “correct” originalism most respects the prudential element. As tempting as it may be to go beyond the positive law in deference to an “imperative natural law truth,” it is not prudent to do so. Sticking to the text and the historical understanding of that text, as Justice Scalia did and Justice Thomas continues to do, is to honor the law’s prudential element.

Forte and Arkes may be said to understand the law’s natural and positive elements similarly, but they have conflicting accounts of how those elements interact. Both find natural law to be a real thing—there are real moral truths that ought to guide one’s actions. Both concur that the positive law is (in its best form) a reflection of natural law; positive law ought to be respected according to its moral coherence with natural law. But where Arkes argues that “moral truth is inseparable from legal interpretation,” Forte laments a jurisprudence that willingly permits all constitutional issues to “be reduced to a matter of finding the natural law answer.”

It is here, Forte argues, that prudence is key. By Forte’s definition, prudence entails using logic “towards a good end, and based on reflection, deliberation, and counsel, in order to find practical means to reach the right result in a particular case.” The practical means to reaching that “good end” today, Forte opines, is originalism. “Originalism is a moral command of prudence,” Forte says. Originalism is the method by which we can preserve the Constitution as a document worthy of our loyalty and respect.

But today’s political exigencies present a conundrum. Denigrating the Founding has become vogue. With the 1619 Project leading the way, the character of the nation’s Founding has increasingly become synonymous with the evils of slavery and racism. It is becoming more commonplace to assume the Founding Fathers and Framers of the Constitution were all irredeemably racist and built the nation on the foundation of white supremacy. And originalism has not escaped these attacks. Recent scholarship has, in varying degrees, associated originalist practices with preserving white supremacy (see, for instance, this article on originalism’s ascendancy as a racist reaction to Brown v. Board or this book on originalism’s progenitors being defenders of slavery from the 1830s).

So, what are we to do? Is there a way to rescue the original meaning of the Constitution but maintain the integrity of the judge’s role to say what the law is, rather than what it should be? If the “better” originalism is imprudent, and the “correct” originalism only serves to remind us of our dark past and draw into question whether the original understanding is worthy of our loyalty and respect, perhaps originalism should simply be done away with. Or perhaps not.

Indeed, it may be prudent for us to look for a “better” originalism and, luckily for us, confronting our past may still teach us valuable lessons for the present. Our current crisis of identity is not unlike that of the antebellum period. As the nation struggled over its identity (a struggle which eventually led to Civil War), the Constitution laid at the center of the debates. Was the Constitution pro-slavery or anti-slavery?

Forte briefly acknowledges this struggle when he mentions William Lloyd Garrison, who maligned the Constitution, identifying it as “a covenant with death, an agreement with hell.” The Garrisonians believed the Constitution to be irredeemable because of its connection with slavery. Interestingly, they used methods of interpretation similar to original intent originalism to arrive at this conclusion. The Garrisonians curiously had an affinity with defenders of slavery on this point—pro-slavery politician John A. Campbell mentioned to the infamous John C. Calhoun that, with just a few modifications, the Garrisonian argument could be adapted to the pro-slavery cause.

Likely for lack of space, Forte does not directly address their arguments, nor does he take up the issue of slavery. Indeed, it would take much more time and effort to unpack the constitutional intricacies presented in the antebellum period than a brief article will permit. Yet even a glimpse into the problem of slavery during that time may still prove useful to resolve the tension between a “better” originalism and the “correct” one. Indeed, we may see that there comes a time and place that something like a “better” originalism can still respect the positive law and, above all, be the prudent thing to do to preserve the Constitution as a document that deserves our respect and loyalty.

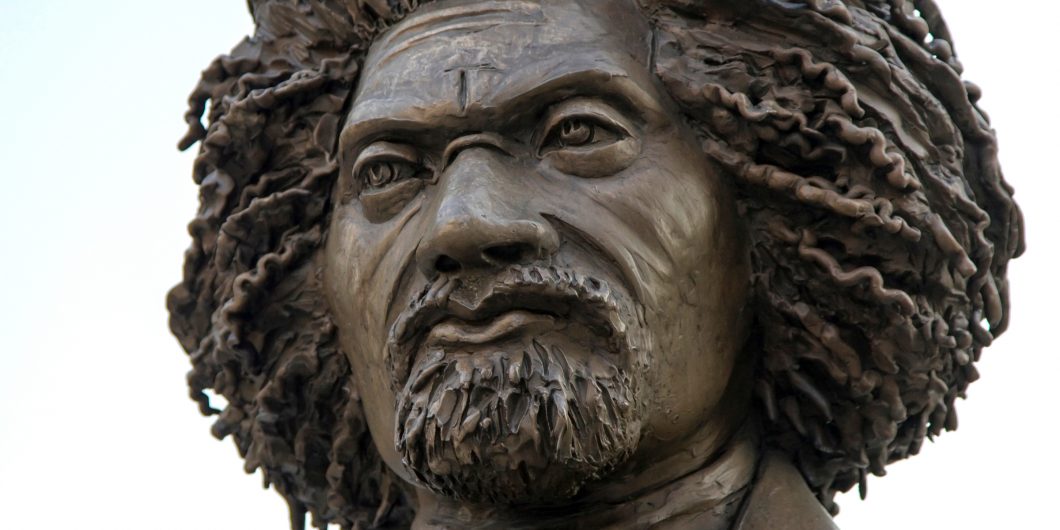

Fortunately, the Garrisonians were not the only abolitionists who had something to say about the Constitution. Constitutional abolitionists sought to wrest the Constitution from the grasp of the “Slave Power” by interpreting it as an anti-slavery document. These abolitionists, including Lysander Spooner, Gerrit Smith, and Frederick Douglass, understood the Constitution as an instantiation of the Declaration of Independence, that its original purpose was to establish freedom for all. “We the people” did not mean “We the [white] people” or “We the [white male] people,” but all persons naturally born or naturalized into the Union. The Union suffered from improper administration, not improper principles. The Garrisonians and pro-slavery defenders were doing the Constitution a disservice by associating it with the perpetuation of slavery. Rather, in the famous words of Frederick Douglass, the Constitution was “a glorious liberty document.”

Constitutional abolitionists understood that respecting positive law did not mean that they disregard the natural law in the way they interpreted the Constitution; nor did natural law require them to disregard the people who adopted the Constitution. But natural law did require them to understand the original meaning in a particular way.

These abolitionists interpreted the Constitution somewhat similar to how originalists do today. They looked to the plain meaning of the words of the document at the time of adoption. When searching for that meaning, rather than argue what the Framers intended to accomplish, they often made arguments based on how the public understood the Constitution. Much like Forte, these abolitionists recognized that the positive law (in this case the Constitution) was binding. However, its binding nature only subsisted so long as it was in harmony with the natural law. Thus, when interpreting the positive law, these abolitionists emphasized natural rights in their methods. As they sought the plain meaning of words, they did so with an eye specifically to the Constitution’s purpose: to protect the natural rights of all persons. They therefore reconciled the Constitution’s many provisions with an anti-slavery agenda that would bring about gradual abolition.

Importantly, not only did their methods respect the positive law and recognize the importance of natural law, but it was the prudent thing to do. Antebellum abolitionists understood the importance of how the Constitution was interpreted. The Constitution shaped the character of the nation; it taught its inhabitants the proper aims of government and, indeed, human life. The preamble stated that the Constitution’s aims were to establish justice and secure the blessing of liberty—in other words, human flourishing. Yet, from its inception, the Constitution was continually darkened by the shadow of slavery. From the 1793 Fugitive Slave Act to Dred Scott in 1857, the anti-slavery cause faced increasing setbacks. Even if the founding generation thought that gradual abolition was the proper policy under the Constitution, by the 1850s slaveholding states certainly did not think so. Bolstered by constitutional victories both in the legislature (Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, Kansas-Nebraska Act, etc.) and the judiciary (Prigg v. Pennsylvania, Dred Scott v. Sanford, etc.), defenders of slavery advocated the cause of slavery as not only a positive good, but as a constitutionally sanctioned institution. Abolitionists sought to stave off the growth of slavery through moral suasion, but they soon realized that moral suasion simply was insufficient in the face of constitutional mandates being pushed by slaveholders. What good was promoting freedom if the Constitution gave legal and moral sanction to slavery?

To fight this battle, abolitionists used natural rights as a lens to interpret the Constitution. For example, some abolitionists argued that the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was unconstitutional for two reasons. First, the purported “Fugitive Slave Clause” did not have the word “slave” anywhere in it. While “person held to service” could have meant “slaves,” it also could have meant those contractually obligated to service, which necessarily excluded slaves due to their inability to enter contracts. The natural rights interpretation, therefore, focused exclusively on the meaning related to those contractually obligated to service. The interpreter interpreted the meaning in a way that comported with liberty. Second, even if the clause referred to slaves, the Due Process Clause prevented the recapture of any slave. The federal government could not sanction slavery nor lend a hand of assistance to the vile institution in any way because such would deprive the slave of his or her natural right to self-ownership and freedom. In fact, the federal government was not bound to respect slavery in any instance for no law could properly permit someone to enslave another.

Admittedly, originalists today certainly would have had a hard time coming to a conclusion similar to constitutional abolitionists. Originalists focus on interpretation as a strictly empirical endeavor—understanding the meaning of the Fugitive Slave Clause or the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause, for example, does not require a moral investigation into words and how they may be reconciled with the meaning of “liberty.” Arkes has a point when he states that originalism is essentially a positivist jurisprudence that only has respect for the majority as a moral authority. The late Justice Scalia made it a point of pride that he only respected the rule of the majority as reflected in the law, despite his own moral convictions. Arkes laments this, finding that it elevates positive and prudential elements at the expense of the natural element of law. Yet, Forte reminds us that we cannot simply “measure every law according to its correspondence to a natural law norm.” Such would only change the nature of the problem from eliding natural law to eliding positive law.

However, looking to the past and how constitutional abolitionists met the problem of slavery and the Constitution challenges us to reconsider how we understand this tension between originalism and natural law theory to see if there remains a better way to reconcile the two. What is more, it shows us that there can be a time when taking more seriously natural law principles over mere positivism can indeed be the prudent thing to do. Constitutional abolitionists understood that respecting positive law did not mean that they disregard the natural law in the way they interpreted the Constitution; nor did natural law require them to disregard the people who adopted the Constitution. But natural law did require them to understand the original meaning in a particular way—it guided them to reconcile that meaning, as much as possible (and at times quite creatively), with natural rights.

There could be a method that has both the reliability of originalism and the moral authority of the natural law. Indeed, we need a method that can reconcile the Constitution with natural rights. Originalism as it is practiced now likely would not have been equal to the task in the antebellum period, and it may not be equal to today’s challenges. The Constitution can only demand our respect and loyalty if it adequately reflects the natural law and thereby protects our natural rights. Originalism has great appeal given its rigorous methodology, but it lacks a certain moral quality that can redeem the Constitution’s soul. Arkes and company have importantly challenged originalism in what feels like a watershed moment in our nation’s constitutional history. Indeed, they have already done much in an attempt to carve out a new path. Perhaps more will contribute efforts to answering whether we can truly find a “better” originalism. Perhaps that effort will generate a robust theory of interpretation, much like originalism has in the past four decades. For now, constitutional abolitionists provide a sketch of how we can understand the Constitution and its provisions in a way that demands our loyalty but also respects all elements of law, natural, positive, and prudential.