How did taxes become something we "do"?

Reforming a Fiscal Revolution

Almost exactly 200 years ago, the British House of Commons rejected a peacetime income tax. Henry Brougham, a Whig member of Parliament, mobilized public opinion against the tax, and after a raucous debate in the Commons, his side won by 37 votes. This revolt against the government that had led Britain to victory over Napoleon barely a year before, and the government’s response, marked an important turning point. It shows that Britain’s path to military and economic preeminence in the 19th century was far from smooth, for this was a time of social upheaval and political conflict. Taxation became a flashpoint for controversy.

William Pitt the Younger had introduced the income tax in 1799 as an emergency measure to cover the rising costs of fighting Revolutionary France. Before then Britain had relied, in war and peace, on indirect taxes coupled with borrowing. When revenues from indirect taxes hit a ceiling at the same time that borrowing costs spiked, a crisis hit. Pitt addressed it, followed by his successor, Henry Addington, who shelved the income tax during a brief peace only to revive it with a high rate and more effective enforcement when Napoleon Bonaparte started the war again in 1803. Property paid the costs of a conflict that was first framed as a war to defend property from revolutionary chaos and then as a war against military despotism.

An existential struggle justified the income tax and also the expansion in government debt it helped service. Often described as a property tax, the levy applied to income earned on property, to individual enterprise, and to dividends from government debt. People resented it as a kind of fiscal inquisition for the way that its collection intruded on their business activities. Reporting earnings was a new phenomenon. With other wartime taxes, however, the income tax meant that the wealthy in Britain now provided a higher proportion of revenue than they had over the previous 120 years.

The victory at Waterloo in June 1815 ended Napoleon’s career, and two decades of war, but the peace brought a sharp economic transition and brewing social unrest. Britain struggled to service debts from the struggle along with ongoing expenses related to demobilization. Although the government had pledged to drop the income tax at the war’s end, Lord Liverpool, the Tory Prime Minister in office since 1812, saw no other way of easily financing the transition to peace. Taxes on consumption burdened the working and poorer classes while raising less revenue than the income tax. Liverpool considered a key objective the servicing of the national debt to uphold public credit and keep down interest rates for private borrowing. Fiscal responsibility, however, was a hard sell.

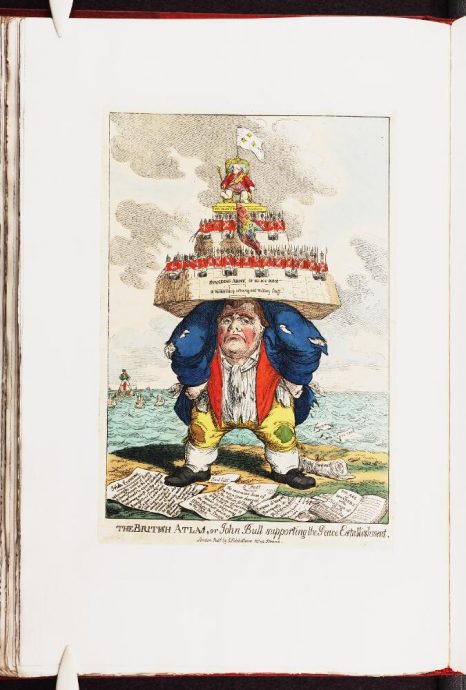

Longstanding complaints about the patronage and pensions that government spending involved—what radicals denounced as “old corruption”—made arguing for the income tax even harder. Political cartoons depicted John Bull, the emblematic average Briton, staggering under the weight of a military establishment far beyond peacetime needs (see illustration above). Radicals outside Parliament complained that the tax bled the productive economy to fund an opulent court, political patronage, and well-connected financiers who held government debt. Pamphleteers likened the situation to a leech feeding upon the body politic. A postwar economic downturn sharpened accusations that government profligacy drained wealth from the enterprising, especially since the income tax fell on middle class professionals and businessmen.

In early 1816, Brougham tapped the discontent by mounting campaigns in provincial cities to send petitions to Parliament. It was a clever move. Presenting each petition occasioned a debate about the income tax. Newspaper reports then prompted more petitions and further debates. Liverpool’s colleagues—he sat in the House of Lords—faced constant pressure that wore down support for the tax. Lord Castlereagh, the foreign secretary who also managed government business in the Commons, struggled with challenges on financial measures. Never before, Castlereagh lamented, had the Commons been so unwilling to hear him. The Chancellor of the Exchequer, Nicholas Vansittart, fared even worse in debates. Acclaim that the government had won for success in war and diplomacy had become last year’s news for a restive Parliament. Moreover, a Whig opposition that had been deeply unpopular, distrusted, and excluded from power since the 1780s was emerging from the back benches to speak for a wide spectrum of British opinion.

Mishaps did not help the government’s case. Castlereagh, notorious for garbling his words, complained about the public’s “ignorant impatience of taxation.” A critic jibed that he favored “every tax but syntax.” Old tax records sold as paper to a cheese merchant, who happened to use them as wrapping for his wares, gave Brougham a devastating anecdote about customers devouring their neighbors’ financial information along with the cheese. Rather than dropping the measure, Liverpool insisted that any repeal was the responsibility of the House of Commons. Ministers in Whitehall had the duty to propose the measures they thought best for the country.

He also believed the tax would be sustained by a 40-vote margin. Instead it lost by 37, in a packed House with crowds outside awaiting the result. A famous cartoon depicted Brougham clubbing the monstrous tax with a rolled list of the voting majority, while the tax’s supporters and the Prince Regent fled the scene. In 1816, it was not yet the custom for such a defeat to bring down a sitting government; but the public anger expressed was forceful enough to put ministers on warning for their future.

Liverpool cut state expenditures and enforced strict economy on the government. His policy meant reducing the army and navy along with the civil administration. Even the Prince Regent’s court economized sharply. The government also reduced indirect taxes, even though it meant additional borrowing over the next five years. Castlereagh insisted that if the Commons voted income tax relief for property owners, then ministers should protect the less affluent. Brougham and other Whigs overreached in their charges, alienating many MPs who had sided with them over the income tax. Ministers also made a stronger case of their own. A debate on the navy’s budget checked opposition when John Wilson Croker, Secretary to the Admiralty, read figures showing that expenditures for civilian administration had risen during the first year of peace in every previous war since 1697 from additional business as ships and sailors returned from deployment.

Ministers were now aware that they could not expect the support that they had enjoyed in wartime. Majorities on particular votes would not suffice without speeches in Parliament justifying the government’s conduct. Newspaper reports of debates in Parliament shaped opinion beyond Westminster and the capital. Critics spoke as much to the wider public as to the members of Parliament they criticized. Economic hardship brought popular disturbances and agitation for reform that alarmed the propertied classes. Protests crested in 1817 and again in 1819. Efforts by cavalrymen to break up a mass meeting at St. Peters Fields, outside Manchester, caused crowds to panic and ended in several fatalities. A journalist dubbed the incident “Peterloo,” an ironic reference to Wellington’s victory over Napoleon.

Recognizing the threat that this disaffection posed, Liverpool made a concerted effort over several years to shrink the costs of government. Aiming to demonstrate his government’s ability and willingness to meet public complaints, he dismantled much of the administrative system that had carried Britain through its 18th century wars. That structure also had provided government with jobs, contracts, and pensions to build political support and parliamentary majorities. Along with other measures against corruption, Liverpool took away the opposition’s case with steps towards a much smaller and less costly British state.

The return of prosperity in the early 1820s gave Liverpool the flexibility to pursue a larger reform program that historians have called “liberal Toryism.” Far from being corrupt or self-interested, the establishment showed that it could—and did—pursue the public good within the existing political system. Economic reforms that lowered the cost of government were one part of the program. Dismantling mercantilist restrictions on trade was another that made an important step toward laissez faire, which expanded commerce and stimulated economic growth. Legal reforms, including a reduction in the number of capital offenses, addressed particular complaints that Brougham and other opposition figures had pressed. Even on the contentious question of reforming parliamentary representation (the famous problem of the “rotten boroughs”), Liverpool accepted measures to stop open abuses, and in this way tried to deflect demands for sweeping institutional change. As he said in a debate over transferring seats from a corrupt borough, he argued not “as a parliamentary reformer, but as an enemy of all plans of general reform.”

The somewhat calmed political waters were an encouragement to liberal Toryism, but continued opposition pressure and popular unrest made the strategy even more necessary. Ministers went beyond mere economy to demonstrate willingness to redress grievances. Liverpool contrasted reforms aimed at mending and improving a frayed institutional fabric with those intended to replace it. Eventually, his strategy drained support from the opposition Whigs and popular reformers by taking their issues off the table.

Denying critics the leverage they had employed during and after 1815, liberal Toryism set the government on a firm footing for much of the 1820s. Political turbulence returned only after a crippling stroke drove the long-serving Liverpool from office in 1827, whereupon factionalism hobbled the Tory party. More economic difficulties compounded its problems. Discontent again got the upper hand, but even so, the movements for reform of 1830 through 1832 fell short of the revolution that some observers feared. Reform of the Corn Laws came, as did other landmark changes, but this was reform, not revolution—for which Liverpool was in no small part responsible.

It is remarkable for Americans to consider how, 200 years ago, the loudest cries against taxation came from liberals and radicals. Their campaigns brought the impact of public opinion to bear on those in power. Brougham was a pioneering figure, operating as a party chairman before the position existed. He led the Whigs in a crusade that made a peacetime income tax anathema in the country for years, until Sir Robert Peel revived it as temporary measure in 1842.

In the meantime, however, Liverpool withstood Brougham’s challenge. He adopted reforms that ended abuses and cut expenses to show that governing institutions did not have to be swept away—they could be made to serve the nation as a whole. The Second Earl of Liverpool earned a place among Britain’s great conservatives, even as his reputation faded over the long ascendancy of Victorian liberalism. Confrontation over the income tax after the Napoleonic Wars were won highlights a tension between concerns about the burdens of taxation and prudent fiscal policy that resonates in politics today.