In Coppola’s telling, the American way of war tends toward either incompetence or brutality.

Remembering Patton

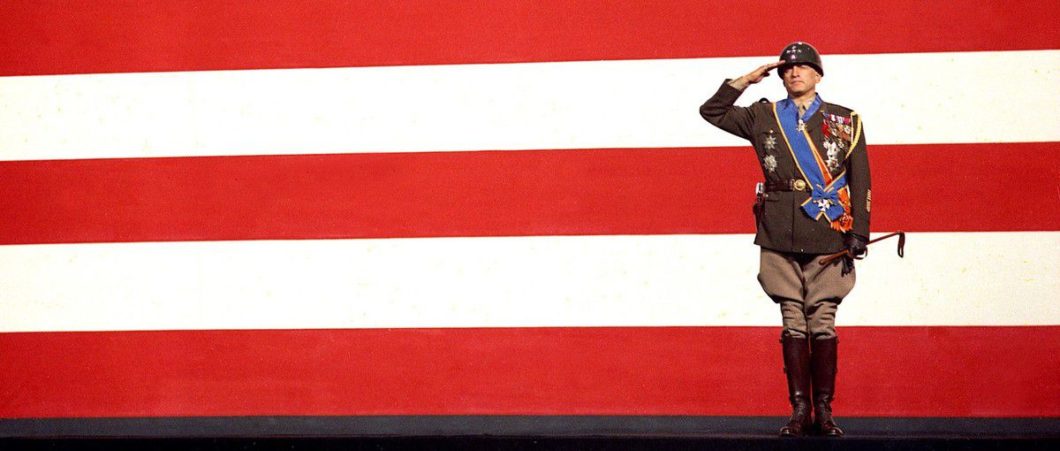

This Memorial Day we also celebrate the 50th anniversary of the best American war movie, Patton, which won seven Oscars, including Francis Ford Coppola’s first, for the screenplay. This portrait of an American hero is especially necessary in our times, when we are faced with crisis only to find we lack comparable leaders on whose greatness we can rely to see us through.

George S. Patton was the greatest American battlefield commander of World War II—and his life demonstrates both how out of place a martial aristocrat seems to modern Americans, as well as why we need a touch of such greatness. To us, winning wars doesn’t fit the language or practice of our leadership, so he is an exotic figure, but he seems to speak for most of us—we are not happy that our leaders cannot achieve victory and, through it, peace. We are, indeed, unhappy with our institutions, which seem paralyzed. Patton embodied the tougher side of the American spirit, the restless seeking after victory in face of obstacles, and the love of glory and honor that usually only appears in our pursuit of athletic or commercial success.

Great Men and Executive Power

Indeed, Patton shaped his character in order to fit this all-American love of undertaking difficult enterprises, achieving astonishing victories through a combination of hard work, talent, and technology, and never relenting. He was all about discipline, speed, and logistics. He is memorable because he embodies what the Federalist tells us about the nature of modern executive power. But unlike most presidents, he had greatness of heart, which Coppola so admired that he made a movie about it.

Patton was as necessary in the European war as MacArthur was in the Pacific, and was likewise a figure we compare to demigods rather than ordinary officials in government institutions. But he was also needed in 1970, when the movie revived his reputation, and he is needed again 50 years later—because we are constantly in danger of forgetting what kind of men we need to deal with our crises, when the nation seems resigned to paralysis and suffering.

Coppola understood this very well and he therefore concentrated on revealing character—what does it really mean to be a captain in the ancient sense, to rule armies in order to save your country? The movie neglects the technical side of Patton’s career and only hints at his lifelong study of history, but it simply assumes skillfulness to be part of his character.

Only when we see a man of such ability, who commands by excellence, do we really understand an army’s purpose. At least since World War II, we have placed too much faith in technology and institutions, and not enough in the power of individual character or the capacity of great leaders to make order out of chaos.

Character is the hardest thing for us to study and so Coppola insistently presents the mysterious, romantic part of Patton’s character over the more calculating, contemplative side of his character. The film predominately shows us the man who wrote “Through A Glass Darkly,” rather than the one who painstakingly composed tactical manuals and combed history for lessons in command. It is true, though, that he believed in reincarnation and longed to have lived and fought glorious ancient wars. He never wanted to be anything but a soldier—his every interest was aristocratic. Patton belonged to the Romantic side of America—his ancestors fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War.

Heroism in Aristocracy and Democracy

Being an American and being a Roman hero are very different things, but both contexts elucidate something about Patton’s character. So the movie starts with a version of the most famous speech Patton gave, his “Address to the Third Army” before the Normandy invasion, in which the great general reassured his inexperienced men that they will prove good soldiers—war itself, which taught him, will also teach them, but now he’s addressing America directly.

Then the movie shifts to the invasion of Casablanca, where we see Patton awarded a medal by the Sultan of Morocco and then visiting the site of Carthage. Instead of the casual, informal modern attitude, he forces all his soldiers to behave with utter propriety, and this concern with the beauty of order quickly proves to be crucial for victory in battle—men’s beliefs tie self-respect to strength, including strength of will. The men suddenly see everything make sense and discipline becomes an image and engine of their command of the chaos of battle.

After the German defeat in North Africa, the action shifts to Sicily, another land invaded by every important civilization in Europe. There, Patton had visions of glory that proved decisive to his practical work, which proved that the American armies were as good as any in Europe. His superiors do not understand at his level what it means to lead an army, and they constantly get in his way. Like Sherman before him, Patton believed in decisive action, aggressive war, and in tough training for free citizens who aren’t soldiers for life. He also believed in a form of warfighting that would return his men to civilian life as quickly as possible. But this was the opposite of the management of war imposed by Eisenhower, in accordance with elite preferences. Like Sherman, Patton was for fighting war to the end and returning to peace. He thought it much crueler to kill people piecemeal, for nothing, by formalities and conventions, than to force harsh battles, lose only the men lost to battle, and save the rest of their lives for peace.

This is the secret meaning of the infamous incidents which Patton blamed for his removal from command—he slapped two soldiers for cowardice who apparently were suffering from what we now call PTSD. He failed here, and couldn’t see the possibility that the war might inflict moral and psychic injury on those under his command.

Finally, after the Roman Empire and the European empires must come a new American Empire, and Patton’s career furnishes the needed example again. His arrival in Europe is that of a ghost—he is in charge of a phantom army intended to deceive the Germans, as though his mere reputation will scare them into paying attention, thus discounting the real landings. But he also trained an inexperienced army for D-Day and, as his prediction that the invasion of Normandy would stall for incompetence proved true, he was sent into battle. Over the last year of the war, he achieved amazing victories, especially compared with the broad-front balancing act of Eisenhower’s command and Field Marshal Montgomery’s brainchild, Operation Market Garden, which was a costly failure.

Here, Coppola gives us a strange companion to the previous examples of combining beauty and power. It may seem mere chance that Patton starts his European campaign by cursing like a common soldier in his great “Address to the Third Army,” and ends forcing a chaplain to compose a weather prayer when he has to race to Bastogne to save American troops in the Battle of the Bulge. But cursing and oaths are naturally connected, so we see him talk to himself and his staff about God guaranteeing his destiny, despite all setbacks!

Patton is shown declaring his pride for his men—he had trained them to achieve a strength previously considered impossible, indeed, that they disbelieved until the eve of the battle. Patton taught himself to curse in order to appeal and speak in a memorable way in a democratic age—this is similar to bending his genius to the democratic American cause, despite his own aristocratic soul.

Patton prays to the God of David—of the Psalms, the God of hosts, that is, armies. This seems rather un-Christian and is certainly unpopular. But the alternative, fighting atheist wars, may be impossible, so what was he supposed to do?

American Exceptionalism

Patton appeared in 1970, when far-sighted men like Coppola could see that progressive liberalism was beginning to crack. He ended the decade with Apocalypse Now, where the liberal way of war appears as insane. Something more is needed than institutions that enforce conformism, limit influence to a small, self-perpetuating class that isolates itself in a few metropolises, and polish mediocrity in hopes of hypnotizing America with fantasies of celebrity.

Executive power calls forth great men in America. They have to obey institutional requirements and, ultimately, the rule of law, but American constitutionalism is unique for its encouragement of remarkable power in the executive when the occasion calls for it. The other powers check and balance it, since they have the stability the executive lacks, but it has the energy they desperately need. Our nature requires it—we are a nation on the move.

One thing obvious only in crisis is the great resources America can draw on. Patton was a natural aristocrat, with a remarkable classical education, and love of manly striving. We are still able to teach and to instill these loves and these powers in young Americans if we choose to. The past and our very heroes have long been despised by liberals, but if we are to create new elites, we should revive these teachings.

Patton may seem anachronistic, but anachronism comes easily to us, since we do not have the long history and customs that other nations have. America was born modern, but that itself made it easy to bring to America from Europe a remarkable civilization, Christianity as much as modern science, natural and political, the commercial spirit as much as the manly love of freedom, all necessary to the conquest of the continent.

Great men prove what we are capable of, but they also prove that institutions are not by themselves enough. We need to replicate what we can of the education of great men and we need also to change our institutions in light of what we learn from how great men help us overcome crisis. We should correct our typical mistake of preferring technology to soul.

Thanks to Coppola, director Franklin Schaffner, and the remarkable portrayal by George C. Scott, Patton will live in our memories as long as we retain our pride. And with that memory, we retain the ability to learn what it takes to form elites fit to wield executive power and how they can lead Americans in accordance with American character and our hidden resources. This time of crisis should suffice to persuade us we need a new class of leaders.