Presidents come and go but so, as defenders of DACA ought also to know, do judges.

Seven Score and Ten Years Ago

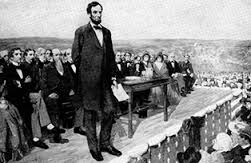

The sesquicentennial of the Gettysburg Address on November 19 requires us to ponder the legacy of the Civil War and Lincoln. This is not some nostalgic romp reenacting Pickett’s charge, but perhaps the decisive political moment of our times. For the best, President Obama will not participate in the official celebration.

This uncharacteristic modesty is appropriate, for Franklin Roosevelt already delivered the Progressive interpretation of Gettysburg and Lincoln’s remarks on the 75th anniversary of the battle, July 3, 1938. FDR’s interpretation of the Address and of the meaning of liberty, equality, and constitutionalism generally have so permeated contemporary thinking that we must confront the original source of these errors in order to free ourselves to understand Lincoln as he thought and acted. This becomes clear on the most elementary reflection on this poem about America, which was once required for memorization by school children.

In a mere 271 words the Gettysburg Address recapitulates the history of western civilization and the role of America in advancing it. Echoing the words of the 90th Psalm (King James) on the longevity of a man, the opening “four score and seven years ago” presages America’s doom—and the way to escape it. The Bible counts man’s lifespan at 70 years (three score and ten), “and if by reason of strength they be fourscore years, yet is their strength labour and sorrow; for it is soon cut off, and we fly away.”

Has America now reached its time of weakness and senility? Is it time for the graveyard? From a continent, to a new nation, to a battlefield, to this cemetery, is it time for America’s death? Did the bringing forth of a new nation “conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal” stumble only to this sad end? Is this what Greek philosophy’s study of nature and the Bible’s disclosure of revelation slouches toward?

But America can be revived it if revisits its founding proposition, and demonstrates once again its truth. A proposition, in the science of geometry Lincoln loved to study, can be proven, in the same way the founders understood the self-evident truth of human equality. For the politics based on human equality has its definitions, axioms, propositions, and postulates, expressed as liberty, representation, separation of powers, and constitutionalism.

In light of the sacrifice made by the fallen, America must now “be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced.” Americans must complete the assignment, not an abstract exercise, but one that requires the commitment of our lives. We in our individual hearts must “take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion–that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain–that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom–and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

If its citizens know and love their country, America does not end here, in ruin and civil war. It experiences rebirth by returning to the founding principles of freedom and self-government, for itself and for all nations on the earth. Both Greek rationalism and Biblical zeal mould and guide who we are, generation after generation. America lives on, perpetually renewed by its citizens’ adherence to the founding principle of all men being created equal. Americans differ in ethnic heritage, religion, class, status, and so on, but as a free people the idea of equality makes us one in spirit and mind.

their country, America does not end here, in ruin and civil war. It experiences rebirth by returning to the founding principles of freedom and self-government, for itself and for all nations on the earth. Both Greek rationalism and Biblical zeal mould and guide who we are, generation after generation. America lives on, perpetually renewed by its citizens’ adherence to the founding principle of all men being created equal. Americans differ in ethnic heritage, religion, class, status, and so on, but as a free people the idea of equality makes us one in spirit and mind.

Against these high duties placed on individual Americans, Franklin Roosevelt posed a radically different interpretation of both the Civil War and the Gettysburg Address. His Progressive view of the Civil War dominates the Progressive left and as well major portion of the right, in particular some libertarians and neo-Confederates who blame Lincoln for the cancerous growth of government. Let the Progressives take the credit, not Lincoln. For good reason the left engages in what Rich Lowry in his fine new book Lincoln Unbound calls Lincoln “body snatchers.” It is a century-old profession, beginning with Theodore Roosevelt, continuing through Mario Cuomo (who edited a volume of Lincoln speeches), and blundering most ridiculously in Barack Obama’s fustian.

Next to his First Inaugural and his Commonwealth Club Address, the key speech for understanding the New Deal’s ambitions is FDR’s Gettysburg remarks. In Roosevelt’s prosaic mangling the Civil War was about “whether each generation facing its own circumstances can summon the practical devotion to attain and retain that greatest good for the greatest number which this government of the people was created to ensure.” This utilitarianism, which of course threatens individual rights, in turn means that for a democracy, “Never can it have as much ability and purpose as it needs in that striving; the end of battle does not end the infinity of those needs.”

For FDR, Gettysburg was fought for unlimited government, the collective “striving” of government, not the individual striving of free men and women, who might rise as Lincoln himself did, from the backwoods to the White House. In a revealing letter (January 25, 1936) that Julie Ponzi pointed out to me, FDR describes Lincoln as “a character destined to transfuse with new meaning the concepts of our constitutional fathers.” The ugliness of Roosevelt’s understanding of America continues on in his 1944 State of the Union Address and its “Second Bill of Rights,” which called for legislative guarantees of economic security, a goal his letter had ascribed to Lincoln.

The left rightly holds up Obamacare as the penultimate in Progressive logic (with single-payer to follow). But its recent embarrassments offer Americans the opportunity to make a truly decisive choice, one that could lead to the questioning of the New Deal itself. For the key problem with Obamacare is not administrative bungling, corruption, or inefficient economics but its assault on the rule of law itself, as political scientist James Ceaser has noted.

Partisan-passed Obamacare deserves a bipartisan response, which I propose. It might lead to the overthrow of not just Obamacare, but of the New Deal. And it enlists Franklin Roosevelt to bring about the demise of big government liberalism.

I urge a series of debates, public seminars, town halls, book club meetings, and symposia on Roosevelt’s First Inaugural. The whole 20 minutes could be broadcast in a half-hour tv program. Excerpts of a few minutes length could also be broadcast, on radio as well. Let his legacy be debated, defended, denounced.

Can his constitutional coup be openly defended? Are basic freedoms to be offered up to the executive will? What about his proposal to shift urban populations to rural areas? And what of his self-comparisons to Christ? There is no better time than a serious discussion of the legacy of the First Inaugural.

In truth, FDR’s bold call for a temporary suspension of the Constitution has been accorded bipartisan approval for 80 years. Now partisan Obamacare breaks that consensus and once again the brute power of liberalism stands before us to be judged. Out of this confrontation perhaps more than a few people may be strong enough to repudiate not only Obamacare but the entire legacy that attempted to give it legitimacy.

Until a few libertarian and other scholars and Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas began raising serious objections, the New Deal was a done deal. Virtually all the objections were made on the edges. We now have a chance to win the civil war that has simmered since 1933 and restore individual liberty and constitutional government, if we understand the Civil War that was fought 150 years ago. We must start with Lincoln’s 271 words at Gettysburg.