“It does the project of equal treatment no favors to extend it beyond its proper scope.”

Silence and Submission

A precedent is being set in Ireland’s parliament with worrying legal implications for Europe. Ironically, this illiberal infringement of free speech is intended to demonstrate our fidelity to European liberal values.

To understand that contradiction, you should know that the Irish sincerely believe that they are amongst the most civilized of Europeans. Europeans, if they remember my country’s existence at all, imagine a foggy Middle Earth, the damp last refuge of the bon sauvage. As such, it has long been a popular bolt-hole for disaffected European intellectuals who wish to live la vida Walden: the patrician actor Jeremy Irons, the controversial painter Gottfried Helnwein, and the radical ecologist Paul Kingsnorth have all gone green and stayed green.

Others come to lie low.

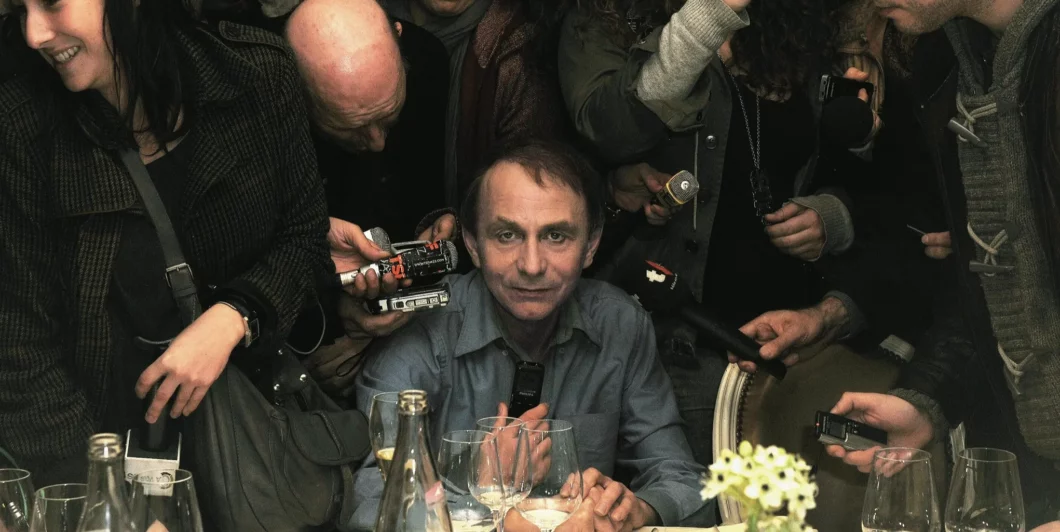

In the early 2000s, Michel Houellebecq retreated to a cottage in Cork to nurse his wounds and lick his grudges. The provocative French author had just had a bruising encounter with cancel culture. It wasn’t called that then, but it was clearly a test run for the twenty-first century’s version of book burning. The books chiefly in question, Atomised (1999) and Platform (2001), were grenades hurled at the pretensions of self-satisfied Parisian elites.

In both books, Houellebecq held up a mirror and laughed. What he saw were aging Soixante-huitards who had exchanged their radical principles at the first opportunity for power, pensions, and luxury holidays. He delighted in dramatizing their hypocrisy, and especially how their accommodations with the most illiberal strains of Islam contradicted their loudly professed feminism. If Houellebecq’s critique stopped there, he might have eventually won the Nobel Literature prize he clearly merits—French writers are expected to be a little disagreeable after all. But he crossed the line with calculated insouciance when he remarked that Islam was, “la religion la plus con” and, even more damningly, that the Koran was “badly written.”

When in 2002 he was charged in Paris for inciting racial hatred even The Guardian described it as, “A blasphemy trial out of the seventeenth century.” Salman Rushdie had been living under the shadow of an Iranian death sentence since 1988 and you didn’t have to share Houellebecq’s opinions to see that this was a vital test case for free speech. Of course, robust defences of Enlightenment values came easier since its antithesis had fallen out of a September sky a year ago in lower Manhattan and murdered almost three thousand innocent people.

In the event, Houellebecq was acquitted. But, mindful perhaps that many would violently disagree with the court’s decision, he headed for the south of Ireland to let the storm blow over. A few years later, he returned home with another book. And the storm? It never ended.

2004 was perhaps the year Europeans knew that this was the new normal. An al-Qaeda train bomb in Madrid killed 193. Back in Holland, filmmaker Theo Van Gogh was cycling to work when he was shot by Mohammed Bouyeri. After slitting Van Gogh’s throat, Bouyeri pinned a note to his victim’s chest. It threatened Ayaan Hirsi Ali, the Somali-Dutch politician who had collaborated with Van Gogh on a film about misogyny and Islam. The phrase “chilling effect” is inadequate to describe the fear incidents like this inspired.

For most writers Islam became taboo. Some were uncowed. In 2011, the Parisian offices of the long-running satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo were firebombed for publishing a cartoon of Muhammad. After they published more in 2012, cartoonist Stéphane “Charb” Charbonnier was put on an al-Qaeda hit list. Houellebecq’s novels are frequently called prescient, but the timing of Submission in 2015 was uncanny. The novel—which imagines France sliding into theocracy after a Muslim president is elected with support from the Socialist Party—was published the day gunmen invaded Charlie Hebdo’s offices and murdered twelve, among them Charbonnier.

Houellebecq, who had received similar threats, soon found himself with police protection. Although the massacre inspired the #JesuisCharlie movement, with citizens taking to the streets of the world’s capitals for free speech, European governments learned a different lesson. Their conclusion was that order could not be kept in a multicultural society with unrestricted free speech. Any doubts vanished that November when 130 more were murdered in Paris. That settled it. A polity may have security or freedom, but not in equal measure.

They acted accordingly in legislatures and behind the scenes, leaning especially hard on social media companies—something that was revealed in the Twitter Files as reported by Matt Taibbi and others. Legacy media was happy to paint its young competitor as irresponsible, and stories of Dark Web misinformation ginned up the witch hunt. But the most consequential example of this creeping illiberalism came just last week. On April 26th, the Irish parliament voted 110-14 in favour of a landmark “Hate Speech” bill, a dramatic expansion of legislation from 1988 that already prohibited incitement of hatred over race, religion, nationality, or sexual orientation.

What Deputy Paul Murphy dubbed “the thought crime bill”—Murphy was one of our few parliamentarians to vote No—gives the state sweeping new powers of censorship. For example, if any Irish publisher dared to publish the cartoon for which Stéphane Charbonnier was murdered, they could be prosecuted. Should Michel Houellebecq take refuge here again, and run his mouth in public, he could find himself in court. And perhaps this time convicted.

In the new Europe, all that is required of the citizen is silence and submission.

The irony is that Ireland’s law against blasphemy was abolished in 2018 after a referendum showed that only 35.15% still wanted it. We Irish like to speak our minds. Our masters, once more, would prefer if we shut up about certain things. Today’s excommunications and fatwas are not issued by thin-skinned bishops or imams, but blasphemy is back on the books.

This grotesque bill is the baby of Justice Minister Helen McEntee. Drafting it last year, she promised “extensive public consultation and research.” This happened in private of course but it was revealed this week by Gript (Ireland’s version of Breitbart) that 73% of the public consultation thought the law was unclear and unnecessary. Of course, when Minister McEntee said “public” she doesn’t mean the great unwashed.

Her government’s headline-chasing inconsistency is a symptom of the disproportionate influence of Irish Non-Governmental Organizations. Some 8% of Irish exchequer expenditure, around €6 billion annually, funds our crowded NGO sector. One of the few NGOs not sharing these spoils is Benefacts—a group that tracked this state spending. What a surprise that Benefacts was defunded in 2021 by the Department of Public Expenditure. How efficiently this conflict-of-interest works can be seen as Minister McEntee’s bill waddles into the world. The loudest voices supporting it are the NGOs who lobbied for it and helped the minister draft the legislation.

Sceptical readers will ask, if this is really so draconian, how did the Minister get away with it? Well, it helped that no one really knew about it until last week. The docility of the Irish press can’t be understood I’m afraid without a whistlestop tour of Northern Ireland. When violence began in 1968, southern politicians worried about it crossing the border. They fell back on censorship, forbidding the state broadcaster RTÉ from promoting the aims of the IRA in any way. Like Minister McEntee’s new bill, this law was hastily drafted. RTÉ sought clarification. They were rebuffed. When they proceeded to report the news, something that involved interviewing IRA spokesmen occasionally, the government summarily fired RTÉ’s board. These laws were later expanded and newspaper editors who defied them were threatened with prosecution.

This sorry episode didn’t help Northern Ireland, but it did instil in journalists a habit of bovine deference, with some honourable exceptions. They also know that the bill is mainly about policing online comment, and who ever objected to competitors being regulated? That’s why most Irish people only heard of this law when Elon Musk tweeted about “a massive attack on the freedom of speech.” Many still wonder why a government that has failed to deal with a wave of assault, theft, and vandalism in Dublin in its tenure is inventing new crimes.

The bill is now set to be debated by the Senate, a toothless body with no appetite for biting. After that formality, it will be tested in the courts. Anyone who studied this bill, anyone not on the payroll, knows its expansive incoherence will be then revealed. As Deputy Murphy said, “It goes against the basic idea that actions have to be taken and that it is the action that is a crime.”

But even if the law’s unconstitutionality makes it practically unworkable, that finding will be underreported, just as its drafting was. This bill has already done what it was intended to do: instil fear and sow uncertainty. Its eventual victims will be working-class people who would never vote for Minister McEntee’s party, Fine Gael. After a few examples are made and publicized, confused citizens will err on the side of caution and bite their tongue rather than risk a blunder that could cost them a promotion, a fine, or five years in jail.

The last time Irish puritanism was at such high tide was in the early decades of the Irish state. That was when the Blasphemy law was first put on the books. Minister McEntee’s predecessor, Kevin O’Higgins argued that no government could be trusted to police speech. The do-gooders knew better. The Committee on Evil Literature (yes, that really was its name) was given wide powers in 1926. They used them capriciously, banning books by Frank O’Connor, Brendan Behan, and Edna O’Brien—not to mention Balzac, Aldous Huxley, and J. D. Salinger. That era of official philistinism is now forgotten and, once again, the do-gooders know best.

Theo Van Gogh and Stéphane Charbonnier are dead. Salman Rushdie is blind in one eye. JK Rowling gets regular death threats. And Houellebecq, Dieu merci, is still disagreeable as ever.

In the new France that Houellebecq imagines in Submission, the changes come slow at first. Jews and short skirts disappear. The Sorbonne shuts. Unemployment is “fixed” now that women can’t work. François is a typically spineless Houellebecq protagonist. An apolitical middle-aged academic, he sees how his mediocre colleagues who convert to the new state religion get on and prosper. He swallows his misgivings and bows his head. In the new Europe, all required of the citizen is silence and submission.