No one surpasses Solzhenitsyn in conveying a sense of what it feels to live at and near the center of this kind of vortex.

Solzhenitsyn’s Prescient Account of “A World Split Apart”

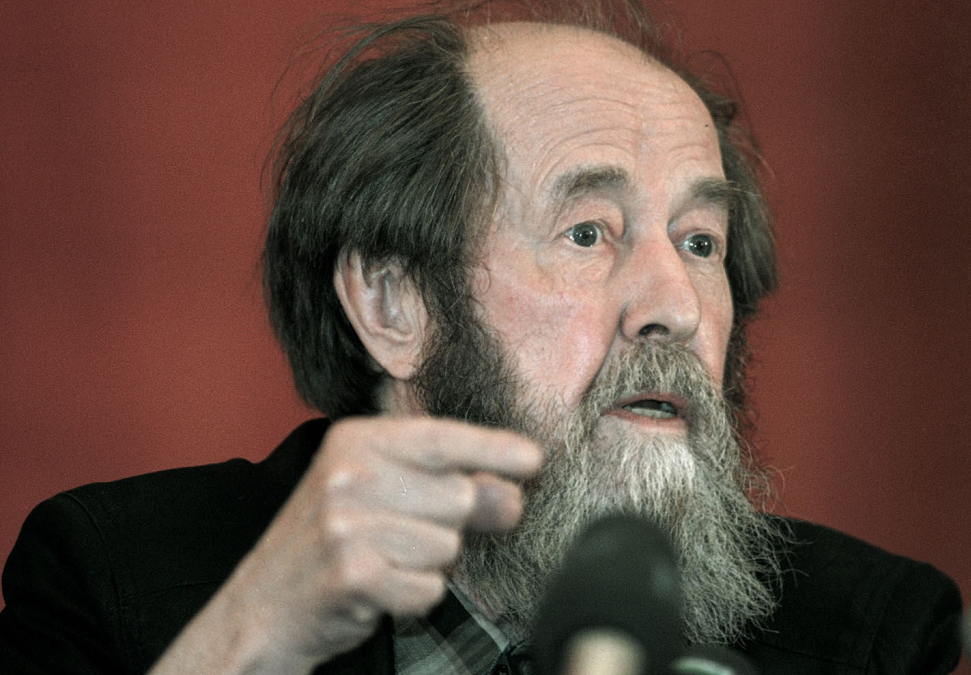

It has now been 40 years since the Soviet dissident novelist Alexander Solzhenitsyn gave the Harvard address that not only flabbergasted those present but predicted the modern world. Solzhenitsyn foresaw the collapse of faith in the West, our addiction to technology, popular culture’s hegemony over deeper forms of learning, political correctness, collegiate censorship, fake news, even Donald Trump. In commemorating the 40th anniversary of A World Split Apart, we read words that are not just relevant, but astounding.

Solzhenitsyn, author of The Gulag Archipelago and One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich and winner of the 1970 Nobel Prize in Literature, was expelled from the Soviet Union in 1974 after decades of opposition to the communist regime. After living in Cologne, West Germany and Zurich, Switzerland, he settled in Cavendish, Vermont, in 1976. Two years later, Harvard University awarded the 59-year-old writer an honorary doctorate and chose him as commencement speaker. His June 8, 1978 address happened to be Solzhenitsyn’s first public statement since his arrival in the United States.

There is enough material for several books in “A World Split Apart,” but the speech, in rough terms, breaks down to six themes.

Decline of Courage

“The Western world has lost its civic courage,” Solzhenitsyn told his audience, “both as a whole and separately, in each country, each government, each political party, and, of course, in the United Nations.” This was most obvious in the attitude of many Westerners toward Soviet aggression—particularly “among the ruling and intellectual elites,” causing “an impression of loss of courage by the entire society,” Solzhenitsyn said. “Political and intellectual functionaries exhibit . . . depression, passivity, and perplexity in their actions,” and “even more so in their self-serving rationales as to how realistic, reasonable, and intellectually and even morally justified it is to base state policies on weakness and cowardice.” Our elites “get tongue-tied and paralyzed when they deal with powerful governments and threatening forces, with aggressors and international terrorists.”

Spiritual Collapse

Solzhenitsyn argued that the suffering endured by countries taken over by communism had made their citizens tough spiritually and politically, so that an end to totalitarian oppression, while desirable, would not be an improvement in all respects if these societies were to become Westernized. During the decades spent under communism, the peoples of Russia and Eastern and Central Europe “have been through a spiritual training far in advance of Western experience. The complex and deadly crush of life has produced stronger, deeper, and more interesting personalities than those generated by standardized Western well-being.” The “human soul longs for things higher, warmer, and purer,” he said, than the consumerism of the West.

In Solzhenitsyn’s account, “the prevailing Western view of the world which was born in the Renaissance and has found political expression since the Age of Enlightenment” became “the basis for political and social doctrine and could be called rationalistic humanism or humanistic autonomy: the proclaimed and practiced autonomy of man from any higher force above him. It could also be called anthropocentricity, with man seen as the center of all.” This “humanistic way of thinking, which had proclaimed itself our guide, did not admit the existence of intrinsic evil in man, nor did it see any task higher than the attainment of happiness on earth.”

The result was a hollowing out of the soul, a process that “started modern Western civilization on the dangerous trend of worshiping man and his material needs. Everything beyond physical well-being and the accumulation of material goods, all other human requirements and characteristics of a subtler and higher nature, were left outside the area of attention of state and social systems, as if human life did not have any higher meaning.” Yet “freedom per se does not in the least solve all the problems of human life and even adds a number of new ones.”

Corruption of the Press

Decades before Chelsea Manning and TMZ, Solzhenitsyn lamented the dishonorable behavior of the Western media, from their enthusiasm for condemning their own country to their invasion of privacy: “Thus we may see terrorists heroized, or secret matters pertaining to the nation’s defense publicly revealed, or we may witness shameless intrusion into the privacy of well-known people according to the slogan ‘Everyone is entitled to know everything.’” Far greater in value, he said, “is the forfeited right of people not to know, not to have their divine souls stuffed with gossip, nonsense, vain talk. A person who works and leads a meaningful life has no need for this excessive and burdening flow of information.” Consider that he said this at least a decade before the advent of the Internet.

Campus Censorship

Even without any state censorship in the West, Solzhenitsyn observed, “fashionable trends of thought and ideas are fastidiously separated from those that are not fashionable, and the latter, without ever being forbidden have little chance of finding their way into periodicals or books or being heard in colleges. Your scholars are free in the legal sense, but they are hemmed in by the idols of the prevailing fad.” And these fads form “a sort of petrified armor around people’s minds, to such a degree that human voices from 17 countries of Eastern Europe and Eastern Asia cannot pierce it. It will only be broken by the inexorable crowbar of events.” In one observation, he’s taken account of the general failure in the West to perceive that communism would collapse in the late 1980s, and also of the character of Americans coming of age in the new millennium, so in thrall to the idols of political correctness today that they cannot bear to hear opposing views on campus and cannot grasp the nature of the freedoms that have been enshrined in their country’s founding charter.

Legalism

Solzhenitsyn did have praise for one aspect of the West: its legal system. “I have spent all my life under a Communist regime,” he said, “and I will tell you that a society without any objective legal scale is a terrible one indeed. But,” he added, “a society based on the letter of the law and never reaching any higher fails to take advantage of the full range of human possibilities.” While our laws protect the widest possible freedom, “society has turned out to have scarce defense against the abyss of human decadence, for example against the misuse of liberty for moral violence against young people, such as motion pictures full of pornography, crime, and horror. This is all considered to be part of freedom and to be counterbalanced, in theory, by the young people’s right not to look and not to accept. Life organized legalistically has thus shown its inability to defend itself against the corrosion of evil.”

Technology

Solzhenitsyn saw “telltale symptoms” of the effects on society of overdependence on technology. “The center of your democracy and of your culture is left without electric power for a few hours only, and all of a sudden crowds of American citizens start looting and creating havoc. The smooth surface film must be very thin, then,” covering an “unstable and unhealthy” social system. Today, of course, people cannot be separated from their phones for even a few minutes.

A Threatened Society

In a lecture full of striking pronouncements, this warning about the nature and quality of statesmanship stands out. The signs of a “threatened or perishing society,” Solzhenitsyn said, were two: “a decline of the arts [and] a lack of great statesmen. Indeed, sometimes the warnings are quite explicit and concrete.” There has not been a compelling artistic movement in the West in decades. And anyone looking for great statesmanship would be wise to avoid President Trump’s tweets.