The goods of human dignity, human rights, and human liberty can be secured only by a transcendent source and an ontological grounding.

The American Message of Human Rights

In a recent Wall Street Journal op-ed, Melanie Kirkpatrick advocated for a change in our government’s approach toward North Korea’s nuclear threats and totalitarianism that was proposed in a National Institute for Public Policy study. After 30 years of using international law and multilateral instruments to try to convince the regime of its irrationality, a more effective approach would be to put information in the hands of North Korean citizens that could precipitate its collapse. Kirkpatrick likened such a policy to the Reagan administration’s focus on human rights, which hastened the collapse of the Soviet Union. But it has a much older pedigree, being consistent with how the American Founders approached the challenge of promoting human rights abroad, an approach of even broader historical impact.

The intellectual contours of the Founders’ human rights strategy were baked into the political philosophy that drove the Revolution. Endowed with a largely Calvinist skepticism of pretensions to religious and political authority, the Revolutionary generation of Americans had studied and internalized the principles of liberty and republicanism, as well as an empirically-oriented, detached perspective on the foundations of law, and how, in practice, the laws of societies can change. In the tired categories of contemporary international relations discourse, “idealism” and “realism” had not, in their thinking, emerged as contradictory approaches.

Historians have documented that the most widely referenced works in pre-Revolutionary America, in addition to the Bible, were those by John Locke and Baron de Montesquieu. Locke illuminated the universal, iron logic of natural rights based on reason and the only legitimate basis for government in consent. He was, at the same time, a British nationalist who saw that these principles could only be honored by the laws of a nation-state, where political principles can retain a connection to their organic roots, and rules and accountability apply. Locke also advocated for unilateralism in opposing and punishing regimes that violated natural law, since international society was really no society at all, but a state of nature with no overarching legal authority.

Montesquieu made few references to the idea of natural rights other than to observe that not all societies were prepared by their political culture to embrace it. He was no champion of natural rights, but rather a neutral political scientist. The study of Montesquieu instilled an anti-utopian prudence alongside Locke’s revolutionary ideas. In The Spirit of the Laws, published in 1748, Montesquieu taught that the laws of different societies reflect the cultures and mores of those societies. He warned about the danger of seeking uniformity and perfection; no one size fits all. He did not discount the possibility of political change toward liberty, but offered counsel regarding methods. Despotic regimes, Montesquieu wrote, do not in fact have actual laws at all, but only “manners and customs,” and to help liberalize societies in their grip, it is necessary to promote discourse, suppressed in such societies, and “engage the people to make the change themselves.”

The American Revolution confirmed Montesquieu’s theory, as it was possible only after the development of widespread appreciation for a Lockean view on rights and the nature of legitimate government. The Revolution itself promoted human rights abroad by the power of example. Following independence, the United States was economically and militarily weak, and as politically polarized as the country is today. The Founders saw that in proclaiming independence and sovereignty, and in initiating the practice of self-government guided by a constitution, they were at the same time acting on behalf of the freedom of other peoples—promoting freedom by being free themselves. They believed their example portended a new world, its universal relevance being based on the common human nature Americans shared with all other people. They sought not a uniform, global legal order, but to increase the number of societies also honoring human rights, and thus to build a fundamentally more harmonious world.

Following the mass bloodshed in revolutionary France, the Federalist faction rejected a goal of global democratic upheaval, and some, favoring aristocratic over democratic rule, backed reactionary responses. But American political leaders, and members of civil society like Thomas Paine, unabashedly denounced monarchical powers that based their coercion and exploitation on entrenched hereditary privilege.

America’s inchoate human rights strategy reflected the political pluralism the society’s new-founded freedom allowed. Large elements of the political leadership were deeply skeptical of democracy, but there was more consensus about the universal right to natural liberty. America’s message to oppressed peoples, embodied in the Revolution and in advocacy by its leading lights, was that all possess political rights and that they could be claimed through bold political change, but did not offer lessons in what to do with those rights.

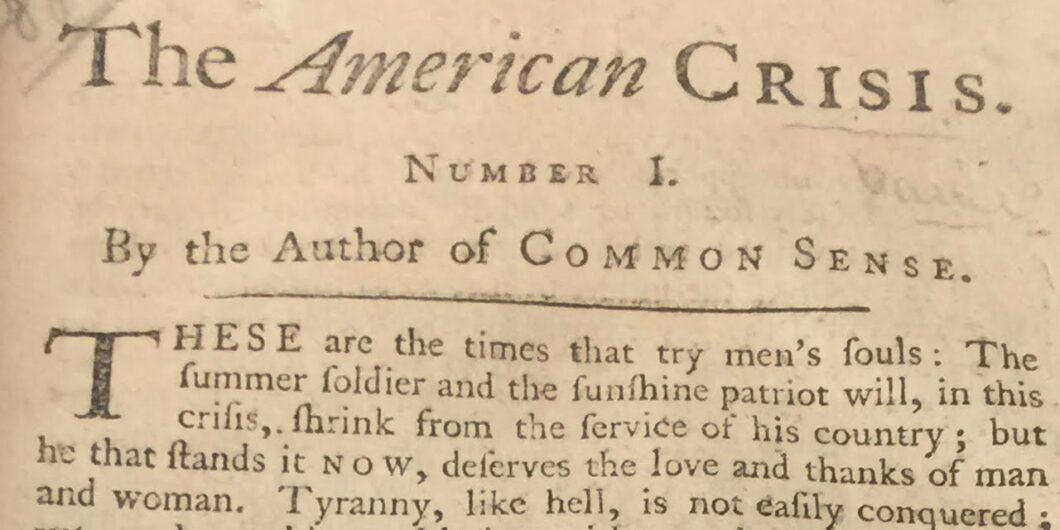

Before anything like modern communication, this message of liberty spread, like a shock wave, in the form of knowledge; in political news, and in passionate, uncompromising political pamphlets that carried the spirit of the radical Enlightenment. Paine termed himself a “missionary of liberty;” along with Franklin, Jefferson, and others, his writings and personality embodied and inspired freedom movements and regime change in a number of European societies, and also in the Western Hemisphere.

For decades, it has been popular to deride early America’s sense of political mission as an arrogant “exceptionalism,” intrinsically at odds with the goals and methods of liberal internationalism that delegitimizes unilateralism in favor of cooperation within a “rules-based” global order. American human rights strategy has today been largely integrated into bureaucratic, multilateral processes in which Locke’s call to honor natural rights has been desiccated through legal routinization, and Montesquieu’s reality-check, grounded in his appreciation of particularism, has been ignored.

Cheerleaders for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and for United Nations human rights treaties claim that they progressively instill a “culture of human rights” through bureaucratic cooperation, leading to political reforms based on international law. But it is essentially a top-down approach whose failures are obvious. While the world has progressively more international law, liberty is in retreat. Indeed, autocratic, human rights-violating regimes have come to embrace the UN human rights regime as one guaranteeing their security by allowing them to hide their abuses in legal obfuscations, and one that pacifies civil society with the promise of reform.

Faith in America’s founding principles, and the integrity of American efforts to promote human rights, has been undermined by historical revisionism claiming that slavery, not individual rights, was their moral core. America’s original message of liberty has generally lost favor at home, with more and more unconcerned about attacks on basic freedoms, and the message, while more relevant than ever, has thus lost potency abroad. It has been largely replaced by sterile, technocratic language promoting collective rights via government and global institutional intervention in economies. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken, announcing America’s program for the United Nations Human Rights Council meeting now underway did not mention political freedom, but said that “we must continue to advance economic, social and cultural rights abroad and at home.”

It is not just in North Korea that a human rights strategy consistent with that of the Founders should be applied. The governments of China, Russia, Belarus, Cuba, Iran, Venezuela, and other autocratic societies deny the principle of natural rights and increasingly seek confrontation with the United States, but their citizens are restive—weary of physical coercion and intellectual suffocation. Now, as in the beginning, America’s strongest defense and contribution to a better world lie in projecting the principle of universal liberty and political freedom.