Without the reinforcement of the Western tradition, the sciences are easily subverted by political pressure.

An American Socrates, Dumbed Down

Ken Burns is America’s favorite documentary-maker, judging by his success over forty years now. If anyone speaks on the authority of popularity as a liberal historian of America, it’s him, and he has spoken on the Civil War, World War II, the Vietnam War, baseball, country music, jazz, and several important American symbols and men. He has taken over the job of national historian for respectable people, following their assumption that patriotic feeling could substitute for long study or sharp judgment.

He’s made so many documentaries that you could educate a well-behaved child on them. He would come out better informed than many people and with a love of America because Burns’s liberalism is not just patriotic, it’s convinced of the goodness of American achievements and the minor character of American troubles. But this child would therefore also come out baffled at the real America he’d have to live in, which he might reject out of disgust, because it’s full of dark passions, and divisions, and it lacks a Burns-like leader. He’d also have no clue about human motives, or the reasoning involved in the establishment of American government and many other important institutions.

The Ideal American

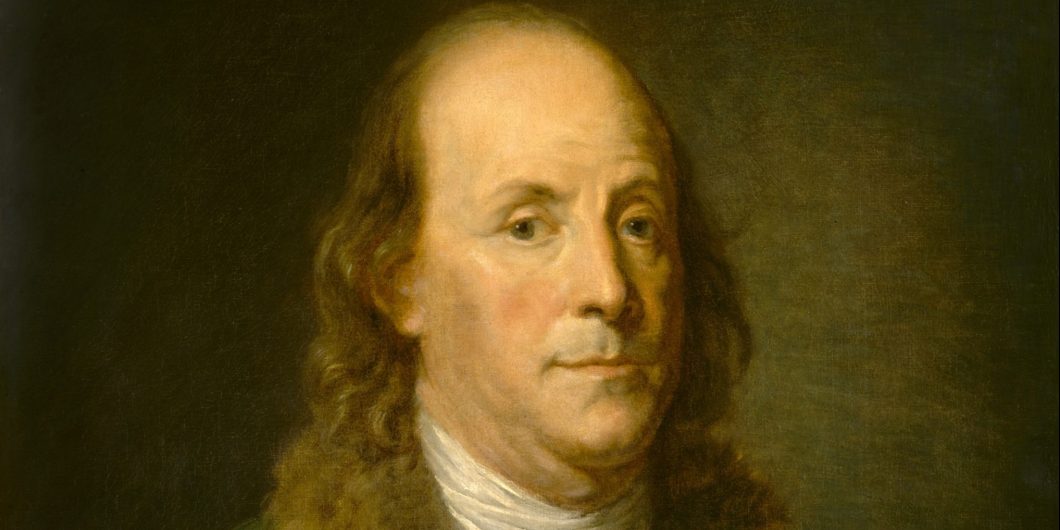

His latest four-hour, two-episode documentary is on Benjamin Franklin, the likeliest of the founders to fit his ideal. Here is a man who might persuade liberals to dedicate themselves to knowledge in a practical way, to the life of entrepreneurship in a philanthropic way, even in a political way, given the various offices he sought and accepted, and to personal improvement in an Enlightenment way. Franklin is Burns’s vision of a Renaissance man: Enlightenment man—he mocks his parents’ piety but is somehow in favor of divine providence; he makes music and musical instruments, but merely for fun; he has a mind for science, but rejects the scientific way of life; he is very involved in improving public life through inventions and institutions, but likes to keep to himself; and he aspires to aristocracy, but is rejected. Franklin is constantly reinventing himself, as the vulgar modern phrase has it—liberating himself from habit, prejudice, or constraint.

Most of us simply do not have Franklin’s talents or his natural superiority of mind which turned to many questions of commerce and science without ever losing sight of the changing political demands made in America and in Britain, so we might not enjoy or even survive much reinvention. Burns would nevertheless like us to learn to reform some things about America in light of Franklin’s ideas. First, Franklin never took patents, out of philanthropy. He made money and had to work so hard for it that it’s embarrassing, given his amazing gifts, but he was free from love of gain. He helped the life of commerce from a healthy distance. Secondly, Franklin was a master of the art of association, the most fitting and needful American art, according to Tocqueville, which keeps us free because we can solve our problems together. Burns’s Franklin reminds us that a healthier society would get intelligent men together to fix problems through institutions. Thirdly, Franklin was unique for tact among the Founders, a master diplomatist, to say no more, and a man from whom we might learn a healthy reluctance to ruffle feathers.

These worthy teachings, however, are contradicted by the documentary itself. Burns wants to show everything about Franklin’s very long and eventful life. This by itself would not be so bad, but he wants to be moralistic about it, especially on the question of race, which is the opposite of discretion. Our pieties also require racial and sexual representation among the talking heads, even if that means we settle for an all-American group of mediocrities rather than great thinkers to speak on the great man.

His portrait of Franklin is accordingly unimpressive, insisting on the magic of experiments regarding lightning, but neglectful of Franklin’s vision of hundreds of millions of Americans—his achievements are but anecdotes, while his failings linger in the mind. His admirers will learn much from the documentary, but through gritted teeth, angry at the condescension. Certainly, it’s neither memorable nor inspiring. Burns’s most insistent, most passive-aggressive criticism is that he wasn’t much of a husband to his wife or father to his daughter, which is both tendentious interpretation of private letters and a waste of the viewers’ time. Watching the documentary, I sympathized with Franklin’s desire to live in England or France, where his astonishing fame freed him from pettiness—his inventions, his conversation, his diplomacy, all get an open stage for once.

The American Socrates

Franklin knew his own greatness better than almost anyone else and presented it with the best concealment in his Autobiography. It’s a document unique in the Founding era, when men mostly were satisfied to be judged by their deeds and remembered by their political reputations. It aims to foster an American character that would depend on reading, but not on the life of scholarship, much less poetry. America is a growing empire, by fortune prepared for continental, indeed world greatness, but certain virtues are required to make good the promise. Franklin knew what virtues were required to deal with the complex life of commerce. This is an economy where men need each other and can thrive only together, amidst an ever-changing situation, so they find it quite difficult to be bound together. He points us to humble self-reliance, a mixing of self-interest and deference to community, which entails an acceptance of common opinion, even if it must be dragged to reason by the yoke of necessity.

We certainly must reexamine Franklin’s great belief that scientific advancement offers an escape from narrowness of mind or the jealous certainties that bedeviled him.

Franklin was at the same time an ironic man. His study of Socrates almost made him a public enemy in Boston:

I procur’d Xenophon’s Memorable Things of Socrates, wherein there are many instances of the same method. I was charm’d with it, adopted it, dropt my abrupt contradiction and positive argumentation, and put on the humble inquirer and doubter. And being then, from reading Shaftesbury and Collins, become a real doubter in many points of our religious doctrine, I found this method safest for myself and very embarrassing to those against whom I used it; therefore I took a delight in it, practis’d it continually, and grew very artful and expert in drawing people, even of superior knowledge, into concessions, the consequences of which they did not foresee, entangling them in difficulties out of which they could not extricate themselves, and so obtaining victories that neither myself nor my cause always deserved…

And I made bold to give our rulers some rubs…, while others began to consider me in an unfavorable light, as a young genius that had a turn for libelling and satyr…

And I was rather inclin’d to leave Boston when I reflected that I had already made myself a little obnoxious to the governing party… and farther, that my indiscrete disputations about religion began to make me pointed at with horror by good people as an infidel or atheist.

He was a precocious teenager, to say the least. As we can tell from Bostonian John Adams’s lifelong suspicion of him, Franklin was not a man in the Puritan mold. The young Franklin thought the religious too arrogant for their own good, to say nothing of the common good. They presumed to know too much about God and hence about how men should live, when there was plenty of evidence that their arrangements as a community were far from perfect and their intelligence was less than superlative. His comic inclination, his turn to political satire and religious skepticism, is all about mocking this pretense of superiority. He went from humiliating people to indulging them because he proved to his own satisfaction that his interlocutors, or antagonists, though they might wish to ruin him, were not particularly wise. Franklin learned not to annoy the religious, coming to believe they need their convictions to make up for lack of wisdom. Had wisdom counted much in human affairs, they would have cultivated Franklin’s genius and made a leader for themselves; indeed, his father at some point wanted to send him to Harvard to become a clergyman, but thought better of it when he consulted his own poverty.

Progress

In short, the boy Franklin was wiser than the aged Burns and had ideas far more radical than anything liberals can imagine these days, since he thought politics could dispense with most moral arguments and conceived of a social arrangement ordered to technological development which we lack. He even faced greater dangers than is commonly realized in his pursuit of scientific transformation of popular opinion. It is always difficult for the mediocre to understand the great, which is why biographies are so rarely well done—we are generally better at guessing which men are very important than we are at explaining why. Documentaries are even worse at dealing with greatness, since the genre makes it a moral demand to not judge the evidence it displays too carefully. So, it’s little surprise that Burns ends up making a mockery of the life and thought of the Founder who found it most important to tell his fellow Americans about his life as he thought best.

It may be easier to grasp Franklin’s radicalism if we translate it into contemporary terms. Franklin would be a scathing enemy of the Progressives who are now the legal-political authority in America, who mutilate minds and bodies. Instead of the scientific advances Franklin practiced and advocated as the best way to avoid poverty and the violence it breeds, we are undergoing an elite madness—one worse than any religious hysteria in colonial America. Under the disguise of pure reason and humanitarian sentiment, this insanity makes use of unprecedented legal and technological power. The elites who claim for themselves exclusive scientific authority would not love Franklin any more than the Puritans whom he baffled with arguments. They would not tolerate his arguments, either, nor, I expect, would Burns deign to associate with such a man.

Perhaps we need to learn from Franklin’s irony how to deal with the dangers of our times. We certainly must reexamine his great belief that scientific advancement offers an escape from narrowness of mind or the jealous certainties that bedeviled him. We have achieved the kind of success Franklin prophesized, peopling the continent whose freedom he helped secure, overawing the British empire, and making new engines and devices for two centuries after his death, But, if anything, daring men like Franklin are rarer now than they were then, as are all other great men—greatness itself is often hated and decried by our elites. We would do well, like Franklin, to return to Xenophon and Socratic philosophy, which can make sense of our inability to understand or foster human greatness.