To shut out all contemporary music without discriminating is not enough—we must attempt to re-educate popular tastes by critique.

The Beat Generation and The Decline of the West

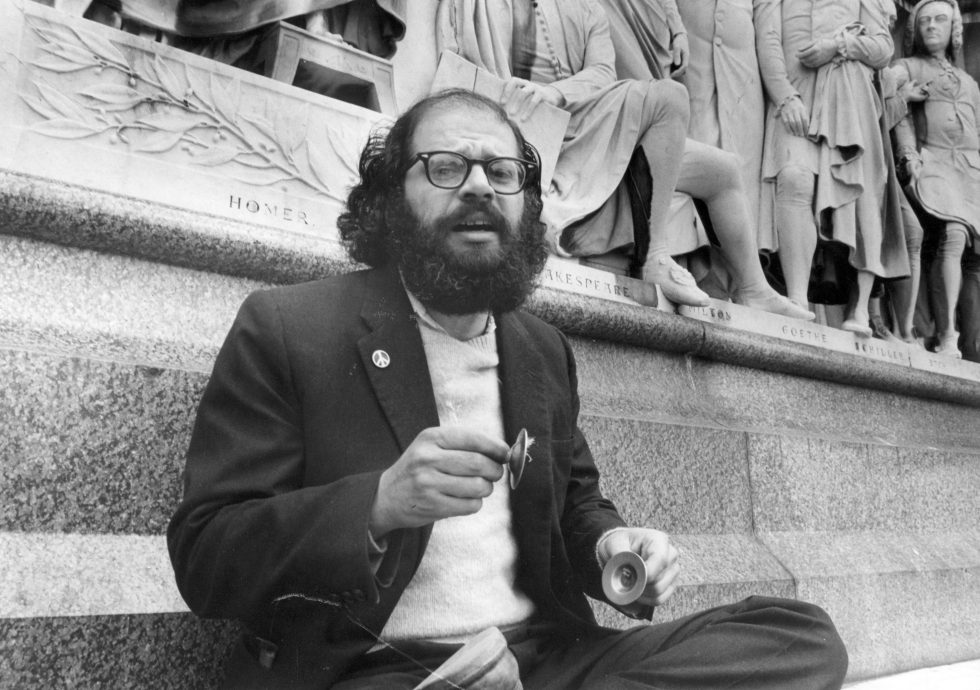

Think of the Beat Generation, the group of poets, artists, and original hipsters who went on the road in the 1950s, and a certain picture emerges: young literary outlaws driving across America, smoking marijuana and rejecting middle class culture. Lead by Jack Kerouac, whose book On the Road is considered an American classic, the Beats included free-spirited outsiders like Allen Ginsburg, William S. Burroughs and Lawrence Ferlinghetti. They were sexually promiscuous, loved jazz, did drugs, and practiced a syncretism of various religions. The Beats, it is popularly thought, had no coherent philosophy other than freedom and a rejection of the square world that they inherited.

But what if that picture is incomplete, or even false? In the new book Hard to be a Saint in the City: The Spiritual Vision of the Beats, Robert Inchausti, Professor Emeritus of English, California State Polytechnic University, argues that the Beat Generation have been turned into “pop culture icons,” and that “a moribund nostalgia threatens to recast these serious religious writers into icons of pop-culture hedonism.” The Beats, offers Inchausti, were among “the most important spiritual writers of the last half the twentieth century.”

Saint is a compilation of spiritual writings by Ginsberg, Kerouac, Norman Mailer, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Michael McClure, Gary Snyder, Anne Waldman, and others. Inchausti centers his argument around the idea that a central text that influenced the Beats, especially Kerouac, was Oswald Spengler’s book The Decline of the West. Spengler (1880-1936) believed that cultures begin as cults, or spiritual enterprises designed to convert the “zoological struggle for survival” into a pursuit of high ideals. As cultures age, they decline into civilizations: “Mechanical operation replaces idealistic zeal,” Inchausti summarizes. “Altruism gives way to the practical life. Everyday existence becomes less a heroic adventure and more an ‘irreligious’ routine.”

As a civilization declines, however, a “second religiosity” can emerge that gives old symbols new meaning even as it ushers in a new age that begins the cycle all over again. As an example, Spengler cites the Axial age, when Buddha refurbished a rigid Hindu system into a method for universal enlightenment.

Allen Ginsberg once recalled that in 1944 William Burroughs recommended to the young Jack Kerouac The Decline of the West. Kerouac and his circle of Columbia University friends were fascinated with what Ginsberg described as “some kind of spiritual crisis in the west and the possibility of Decline instead of infinite American Century Progress.” According to journalist Michael D’Orso, “The novels, poems, and articles that Kerouac produced over the next twenty years are all concerned, in one way or another, with this ‘spiritual crisis’ in his society.” In his writings, argues D’Orso, “Kerouac displays a dissatisfaction with post-World War II American society and the condition of modern Western man in general, an obsession with the concept of time, and a longing for the innocence of a childhood free of the push and pull of time.” Both Spengler and Kerouac “were aware of what they considered the decay of their society, and both examined that decay—one analytically and the other by recreating it in fiction.” In other words, On the Road was not only heralding a new age; it was describing the slow death of an epoch.

One can reject Spengler’s view of history, and even dislike the Beats as sybaritic precursors to the 1960s, but as a matter of academic and historical insight, Hard to be a Saint in the City provides a corrective to the popular perception of the Beat writers as hep-cat lightweights and liberal icons. The Beats shunned not only middle class American culture and consumerism, but often the revolutionary zeal of the hippies and the technology and entertainment industry that would prevent people from following the Buddha’s advice and being present in the moment. Spengler’s influence helps explain why Kerouac, a star college football player, ladies man, and devout Catholic, was never a conventional liberal, and in fact mocked the hippies and even turned far right as he got older. He didn’t believe in utopias or political revolutions, opting to find God in the here and now as one era, or so he believed, transformed into another – which would then, in turn, rise and fall.

This is how Kerouac describes the meaning of Beat in an excerpt reproduced in Saint in the City:

Beat doesn’t mean tired, or bushed, so much that it means beto, the Italian for Beatific: to be in a state of beatitude, like St. Francis, trying to love all life, trying to be utterly sincere with everyone, practicing endurance, kindness, cultivating joy of heart. How can this be done in our mad modern world of multiplicities and millions? By practicing a little solitude, going off by yourself once in a while to store up that most precious of golds: the vibrations of sincerity.

With its combination of traditional Christian sentiment and offbeat hipster phrasing — “the vibrations of intimacy” — this is a typical representation of the Beat worldview. The Beats did not totally reject traditional religion, instead choosing to pick the parts they liked. Immersed in Spengler, Kerouac grabbed whatever he thought were the spiritual expressions that would last as one civilization crumbled and another arose: jazz, novels, art, Nietzsche, sex, drugs, mystical Christianity, Zen. With the possible exception of Allen Ginsberg, who embraced communism, Beats were not utopians. Poet Michael McClure, fictionalized in Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums, rejected the “solutionism” of both the capitalistic right and the revolutionary left, noting, “people say we want a solution, we want utopia, we want bliss, we want progress, we want revolution, we want this, we want that. These are all simplistic solutions. It’s like we are all trapped in solutionism.” This observation would not have been unusual coming out of the mouth of Walker Percy, or William F. Buckley. Cable news and social media have become a long, intense, and hortatory sermon to do something right now, this very minute, to make a dramatic political change because the very fate of something is as stake. Kerouac and the Beats saw spiritual dissatisfaction as an essential part of man’s being, not something to be legislated away.

As the excerpts collected in Saint in the City show, the Beats’ aesthetic could be a powerful force when it was rooted in study, spiritual discipline and the sweat of actually writing books. It became difficult to keep afloat as Kerouac, Burroughs, Ginsberg and others got more involved in drugs, sexual promiscuity, bad politics and morally reprehensible behavior. The darker side of the Beat Generation is left out of Hard to be a Saint in the City, and it’s not a pretty picture. William Burroughs, the Harvard graduate and scion to a wealthy family, became a drug addict whose wife died under suspicious circumstances. (Like Kerouac, Burroughs’ political opinions could surprise. His favorite newspaper columnist was anti-New Deal conservative Westbrook Pegler. Burroughs believed in frontier individualism, valorizing “our glorious frontier heritage of minding your own business.”) Allen Ginsberg, the poet whose seminal poem “Howl” was seized in 1957 by customs officials and declared obscene, degenerated into anti-Americanism, bad poetry, and an unforgivable membership in NAMBLA, the North American Man Boy Love Association. Kerouac sank into alcoholism and was divorced twice. He was living with his mother when he died in 1969 at age forty-seven.