Contrary to the numbers games of today's majoritarians, America's federal republic reflects not a trace of national, numerical democracy.

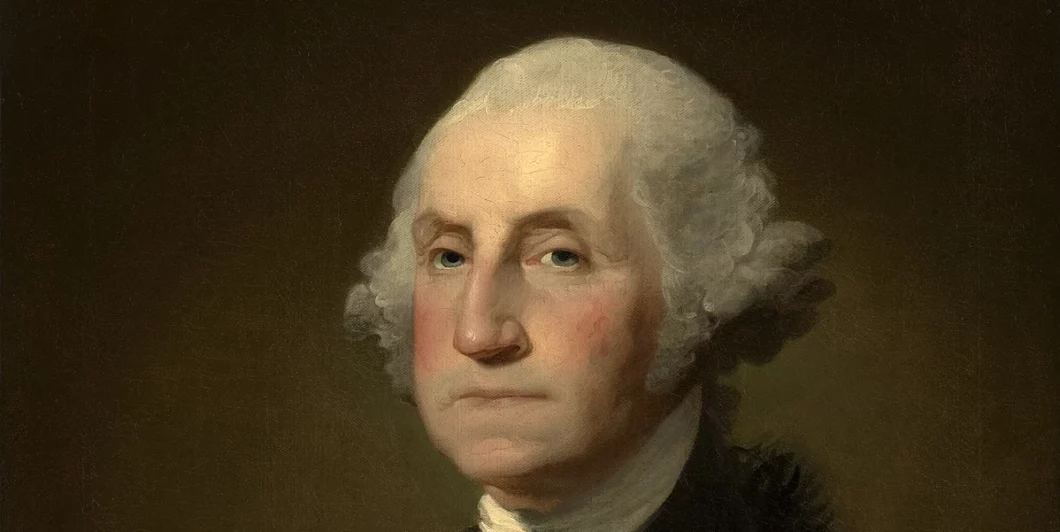

The Catholic Case for George Washington

Americans have long understood, if intuitively, that honoring the American Founding and celebrating George Washington are intrinsically linked. Should the day ever come when the events of the 1770s–1790s do not stir the soul, we’ll have little reason to continue raising a glass every February 22 to the memory of the man who won the Revolution, handed his power back to the civil authorities, presided over the Constitutional Convention, and then held the young union together as the first President of the United States. Likewise, you can bet your bottom dollar that if Americans ever become indifferent or hostile to Washington it will mean that we have given up on the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.

Thankfully, Washington has had fewer critics than other Founders over the years, but he has not been without detractors. The most common critiques of Washington today come from two distinct groups whose views run parallel to one another. The more well-known of the two embraces the ideas of Critical Race Theory, or CRT. This group argues (implausibly) that the most important issue to the leaders of the Revolution and the Constitutional Convention was the protection of chattel slavery, and that Washington, as a slave owner, supported this inhumane goal. Much ink has been spilt defending Washington on this score with ample historical evidence complicating the common CRT narrative—his letter to Phyllis Wheatley, his desire to see the slave trade ended, and the manumission of his own slaves. All of this is well-traveled ground.

I am more interested today in the second group of Washington critics. They are admittedly less common, less aggressive, and far newer to the scene, but they have the potential to be more damaging. I’m speaking of ideological traditionalists, most of whom are Catholic. They have come to associate everything bad in contemporary America as the natural outgrowth of the Founding era’s commitment to Lockean liberalism. I’ve come to call the position held by this newer crowd Critical Catholic Theory, or CCT, the general framework of which holds that the American Founding is best understood as a set of theological, metaphysical, and anthropological propositions that are fundamentally at odds with the classical and Christian roots of Western Civilization.

Clearly, an anti-Catholic sentiment was present in British America, as there clearly was in Great Britain itself, at the time of the American Revolution and those prejudices did not immediately disappear at the time of the Founding. But, without a doubt, the situation greatly improved for Catholics after American Independence. Nevertheless, some proponents of CCT argue (again, implausibly) that Washington’s achievements are marred by his anti-Catholicism. As with responses to the claims of CRT, one has little difficulty combatting such claims with historical facts that show Washington’s respect for his Catholic compatriots during the Revolutionary War (when he banned the celebration of Guy Fawkes Day) and during his time as President (when he penned his famous and gracious letter to the Catholic community in America).

Perhaps a better response to the CCT position, however, is to show the tremendous respect American Catholics at the time of the Founding had for Washington and the nation he helped design. The most authoritative and obvious evidence for this is the pair of eulogies that John Carroll, the first Catholic Bishop in the United States, gave in Washington’s honor. The first was given as a funeral eulogy in December of 1799, shortly after Washington’s death. The second was offered as a general discourse or essay on February 22, 1800, the first observation of Washington’s birthday after his death. Both are examples of Carroll’s unabashed support of America and his respect for its most indispensable citizen.

The first eulogy takes most of its bearings from scripture. Carroll begins with a reference to the book of Sirach: “Nothing can be compared to a faithful friend, and no weight of gold and silver is able to countervail the goodness of his fidelity” (Sirach 6:15). America, Carroll says, has no truer friend than Washington, and that “no weight of gold and silver . . . no reward in this lower world is able to countervail and compensate for the goodness of his fidelity.” The value of Washington’s place in the American Founding, Carroll reminds us, is beyond measure.

From there, Carroll’s first eulogy turns to Romans 13, wherein Paul says that “there is no power but from God. He that resisteth the power, resisteth the ordinance of God.” Carroll uses this passage to admonish those of his own day who are critical of the Constitution to be careful to avoid hypocrisy in their mourning of Washington. Guided by the same observation that opens the present essay, Carroll reminds his audience that one cannot honor Washington without celebrating the nation he fought to free and the government he helped to design.

Carroll goes on to argue that “libertinism and irreligion” are completely inconsistent with the Constitution and the life of Washington—they have no place in America. Those who oppose the Constitution and its laws, either for love of the old Confederacy or love of excessive liberty, are equally guilty of violating Paul’s teaching that we must submit to political authority. He ends by reminding his listeners that we can follow the Bible by fulfilling Washington’s dying wish that “Americans would cordially unite, by uniting would strengthen Government, and there seek their true interest where it was to be found; that after an orderly and well-spent life, they might be entitled to a place among the blissful inhabitants of the Heavenly Jeruzalem.” Here Carroll is admonishing Jeffersonians for being out of step with the Constitution by reminding them of Washington’s warnings in the Farewell Address, which he argues are in keeping with the moral teachings of Christianity.

Shortly after this first eulogy, Carroll sent a letter to the clergy of Maryland with instructions on how to appropriately respond to the governor’s call for celebrating the first posthumous birthday of Washington. Supposing that Protestant and secular organizations would be toasting the late President, Carroll clearly wanted to be sure Catholics do not miss the chance to demonstrate their own patriotic appreciation for the blessings of independence, liberty, and a well-ordered government. He opens the letter saying,

We Roman Catholics, in common with our fellow citizens of the United States, have to deplore the irreparable loss our country has sustained by the death of that great man, who contributed so essentially to the establishment and preservation of its peace and prosperity. We are therefore called upon, by every consideration of respect to his memory, and gratitude for his services, to bear a public testimony of our high sense of his worth, when living; and our sincere sorrow, for being deprived of that protection, which the United States derived from his wisdom, his experience, the reputation and the authority of his name.

He goes on to tell the priests to model their public remarks on Saint Ambrose’s eulogy of the young Emperor Valentinian, “who was deprived of life, before his initiation into our Church; but who had discovered in his early life the germs of those extraordinary qualities, which expanded themselves in Washington.” The reference to Ambrose is meant to remind Maryland’s Catholic priests that God is willing to use all humans as instruments of his Providence regardless of their faith and that it is possible for any person to possess extraordinary natural virtue. Carroll also suggests that Washington’s virtues exceed those of the Emperor Valentinian, and that however much Ambrose was rightfully thankful for the blessings of Valentinian’s just rule, Americans have more reason to be thankful for a man like George Washington whose service included the creation of a decent republican regime that could, if maintained, far outlive a single just ruler.

Traditionally, American Catholics have celebrated the Founding because Providence’s role in its initial success is so glaringly apparent, especially in the life of Washington.

Following his own instructions, Carroll offers a discursive eulogy on Washington’s greatness on February 22, 1800, which he delivered in Saint Patrick’s parish in Baltimore. This second eulogy differs from the first in several important respects. Washington is still praised from a biblical standpoint, but the frequency of biblical quotations is reduced. No longer do we see several quotes from Sirach and a politically charged reference to Romans, but instead a single, long quote from Wisdom 8, that indicates Washington’s dependence on Providence for all the good that he accomplished. The focus on Providence allows Carroll to emphasize the universal appeal of Washington. Unlike the first eulogy, the second does not have any political jabs, though it continues to call, in the name of Washington, for unity under the Constitution. He elevates Washington above the fray, making him—like the Constitution he helped to craft—an object that all are right to look to for encouragement in promoting a nation with “undefiled religion,” accompanied by morality, peace, unity, and liberty.

It is hardly an exaggeration to say that Carroll’s second eulogy refers to Providence in almost every paragraph. Providence, he says, is an artist that impressed a character on the life of Washington so that it might use him as its “principle instrument.” Providence exhibited in Washington multiple endowments and prepared his body and mind for his vocation as a leader of the Continental Army, President of the Constitutional Convention, and first President of the United States. Carroll also says that Providence provided Washington with a guardian angel to help minister its designs upon him during his youth. Even the unflattering parts of Washington’s career, such as his missteps in the French and Indian War, are spoken of as providential so that Washington might learn from them.

And the purposes of “all-wise” Providence are multiple, for not only was Washington the instrument of America’s success in founding a new government, but he is also an instrumental example of a good American citizen and leader. “Would to God,” Carroll exclaims, “the principal authors and leaders of the many revolutions, throughout which unhappy France has passed in the course of a few years, would to God, that they had been influenced by a morality as pure and enlightened, as that of Washington, and his associates” at the First Continental Congress which so soberly approached the issue of Revolution. They, and not France, are the examples Catholics should follow.

Carroll goes on to credit Washington’s success in the Revolutionary War not to his merits, but rather to his dependence on “the God of battles, to whom he made his solemn appeal.” Not only did Washington demonstrate a life dependent on Providence, but he also understood what he was doing and urged his fellow Americans to likewise entrust themselves to Providence’s care, as is evident in his Farewell Address when he admonishes us “to bear incessantly in their minds, that nations and individuals are under the moral government of an infinitely wise and just providence; that the foundations of their happiness are morality and religion; and their union amongst themselves their rock of safety; that to venerate their constitution and its laws is to insure their liberty.” Accordingly, Carroll ends his eulogy by praying that Providence will continue to care for America, and says he is confident it will so long as Americans remember to “gather round the name of Washington.”

Bishop Carroll’s eulogies, while perhaps excessive in their praise by today’s standards, are a good reminder that Catholic critiques of the American republic and the most indispensable of our Founders are a relatively new phenomenon. Traditionally, American Catholics have celebrated the Founding precisely because, as Carroll refuses to let his audience forget, Providence’s role in its initial success is so glaringly apparent, especially in the life of Washington. For Carroll, Washington is evidence of a great God who cares for us. And when we cooperate with Providence, as Washington did, Carroll is confident that God will continue to bestow His blessings upon us.

In this depiction, Washington is not offered as the true Father of the Nation—God is the Father. God is the Founder. God is the Legislator. God is the Executive. God is the Judge. Washington was the willing instrument. So long as Americans follow his example, Carroll is confident America will thrive. If Carroll is right, and if things are indeed becoming chaotic in America, we cannot blame the Founding generation for all our woes. We can only blame ourselves for not being as willingly instrumental as Washington in the Hands of a beneficent Providence.

Carroll’s eulogies serve as a strong response to the CCT narrative of an anti-Catholic American Founding. More broadly, reading them is a great way to continue celebrating Washington every February 22.