The Common Law: Ginsburg Gets It Wrong

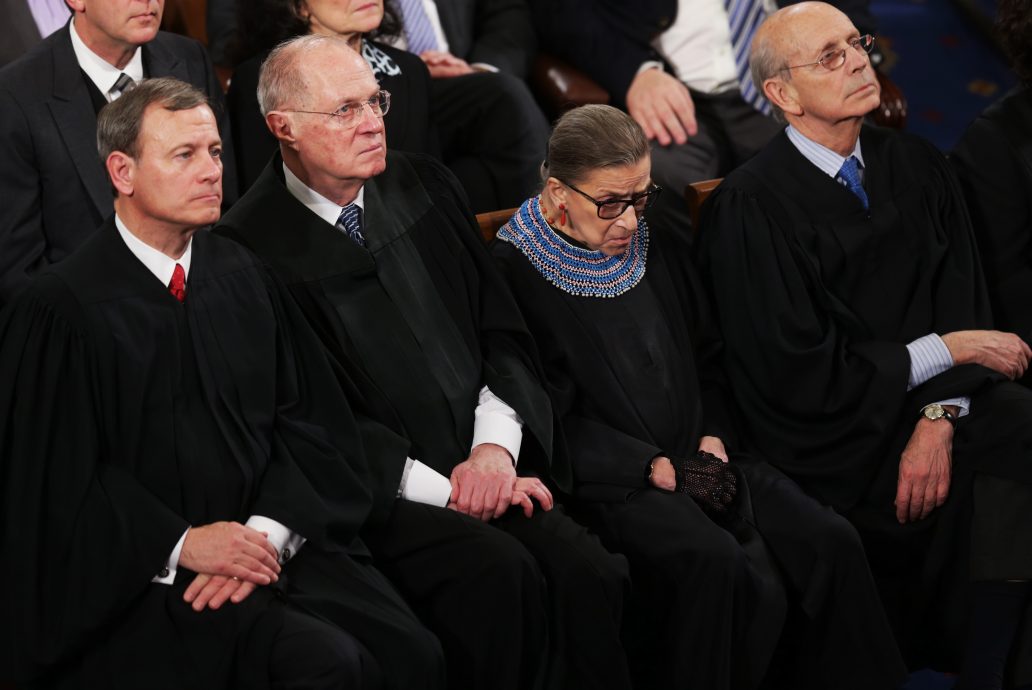

During oral arguments in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), Justice Ginsburg asked a question that has heartened the supporters of marriage revision:

We have changed our idea about marriage is the point that I made earlier. Marriage today is not what it was under the common law tradition, under the civil law tradition. Marriage was a relationship of a dominant male to a subordinate female. That ended as a result of this Court’s decision in 1982 when Louisiana’s Head and Master Rule was struck down. And no State was allowed to have such a—such a marriage anymore. Would that be a choice that a State should be allowed to have?

Referring to this question, London’s Guardian newspaper gushed: “Ruth Bader Ginsburg Eviscerates Same-Sex Marriage Opponents in Court.”

Not exactly.

Ginsburg’s question presupposes an inaccurate (to put it mildly) narrative about the development of marriage law. The law that the Supreme Court struck down in the case to which she referred was neither common law nor civil law. Ginsburg’s characterization of the common law tradition is false in important respects. And her assertion is premised on a positivist fallacy: that our civil marriage institutions today are the product of positive enactments and not common law.

The Supreme Court struck down Louisiana’s so-called “head and master” law in its decision in Kirchberg v. Feenstra (1981). The offensive provision was contained in a statute, enacted in 1912, which a lower court characterized as “the bedrock of Louisiana’s community property system.” That law cannot be blamed on the common law or civil law traditions.

Ginsburg’s understanding of common law appears incomplete at best. For one thing, the common law doctrine of coverture, under which a married woman’s legal identity was subsumed within that of her husband, was abolished more than a century before the Supreme Court ruled in Kirchberg—and without its intervention. State supreme courts and legislatures amended the common law rules to eliminate inequalities between husband and wife, even as they retained important features of common law marital ownership that limited both a wife’s and a husband’s freedom to encumber property without the other’s consent.

An Australian court explained that the abolition of coverture in that common law nation did not abolish the common law marital estate, the form of ownership of real property by married couples known as “tenancy by the entirety.” Rather, eliminating coverture elevated the wife to a place of authority equal to her husband, even as it constrained the individual liberty of both for the sake of the marriage.

In “tenancy by the entirety,” thus modified, “the two spouses constitute a kind of compound owner, resembling an incorporated association of persons.” For this reason, “neither can alienate without the other—even as a member of an incorporated company cannot alienate any interest in the company’s lands; and there is no interest in the company’s lands that can be sold in execution for his debt.”

Common law states (not Louisiana) in this hemisphere have retained and adapted common law marital ownership, too. As the Tennessee high court explained, the modern tenancy by the entirety elevates the wife to “equal legal status” and avoids those “artificial and archaic rules” that placed the wife under a disability.

Not all common law sovereigns have followed this approach. Some (for example, the United Kingdom) have eliminated common law marital estates, and many have embraced what Hanoch Dagan calls the ideal of “free exit” from marriage. But many have retained the strongest features of common law marital ownership, recognizing that the liberty to commit oneself to marriage is a liberty to choose to create new obligations for oneself. As Joseph Raz has observed, the freedom to marry consists of a “degree of unfreedom.” To create a marital obligation for oneself is in part to obligate oneself not to act on one’s own preferences alone.

It’s not in dispute that coverture entailed injustice, but Ginsburg fails to understand what that injustice was, and therefore why it was gotten rid of. Its purpose was not to allow men to dominate women. Nor was the primary injustice of coverture to excuse husbands for abusive acts, although that was in some cases a foreseeable effect of the doctrine. As a judge of the Michigan high court explained, “the disabilities of coverture were seen as serving to protect and benefit [married] women.” Coverture relieved married woman of both freedom and responsibility. Indeed, the doctrine was often challenged after being invoked by a wife. Some wives, having committed their assets in some way, later sought refuge behind coverture from would-be creditors.

Thus what was wrong about coverture was its treatment of married women as if they were not fully rational human beings. When the Texas Supreme Court struck down Texas’ coverture doctrine in its 1851 decision in Jones v. Taylor, that court reasonably treated coverture as an anomaly within the common law tradition. Men were held responsible for the disposition of their assets. Likewise, single women were accountable for their decisions. Only a married woman was deemed “divested of her faculties as a rational being.”

Abolishing coverture reconciled the common law tradition to itself, in which all rational owners enjoy the “right of disposition, control, and management.”

Most striking of all, however, is Justice Ginsburg’s assumption that state marriage laws today constitute a radical departure from the common law tradition of marriage. Where does she suppose those laws came from? The presumption of paternity existed in common law long before state governments codified it in their statutes. Prohibitions against incest, rights of parental custody and parental recognition, the duties of parents which justify parental rights, spousal privileges and immunities: none of these was invented in the late 20th century by state legislatures or the Supreme Court of the United States.

Indeed, the very idea of marriage as an institution of unique and non-fungible dignity, different in kind from friendships (whether same- or opposite-sex), business ventures, social clubs, religious assemblies, and all other forms of human sociability—the very idea that marriage revisionists want to appropriate for same-sex relationships today—is a common law idea.

Justice Ginsburg’s categorical assertion that marriage in contemporary law is something other than what it is in common law is simply wrong. In the most important respects, marriage most emphatically remains what the common law says it is.

During oral argument in Obergefell, the petitioners’ counsel appeared incapable of understanding, much less answering, the Chief Justice’s suggestion that to eliminate from law the “core definition” of marriage is to redefine the institution of marriage. The obvious import of the Chief Justice’s question was this: If marriage is no longer the union of a man and a woman, what is it going to be? That question matters because, if the common law definition of marriage is wrong, then there might be no rational basis for the norms or legal incidents that the common law has attached to marriage, which the petitioners took for granted.

Oddly, the Guardian lauded Justice Ginsburg’s “spatial awareness.” It is a curious spatial awareness that fails to recognize what is holding one off the ground. Ginsburg and the petitioners seemed to want to saw off the branch on which they and the rest of us are sitting.