Public sector unions are exacerbating our criminal justice crisis and making it much harder to educate the next generation during the coronavirus pandemic.

The Decline of Self-Rule

The signs are all around us that the government envisioned by the Framers—self-rule by the people—is on the decline. At the federal level, life-tenured judges often decide matters that are, or should be, the province of the legislative branch (or the states). In the modern administrative state, unelected and unaccountable bureaucrats in executive branch agencies frequently make decisions that the Constitution assigns to either the judicial branch or to Congress, often exceeding the enumerated powers granted to the federal government in any event.

Things are not much better at the state and local levels, where powerful factions (special interests, or “rent-seekers,” in modern parlance) often wrest control of elections (and the budget) to enrich their members at the expense of the voters and taxpayers. I refer, of course, to public employee unions, which represent 7.2 million government workers, accounting for nearly half of all union membership in America. As organized labor has declined in the private sector, public employee unionization has built up an astonishing rate of membership: 35.2 percent of all government workers join unions, versus 6.7 percent of all private sector workers. When employees who are not union members but who are in a “bargaining unit” represented by a union (so-called “agency fee payers”) are included, the public sector share increases to 39 percent, which is to say that unions represent four government employees out of every 10.

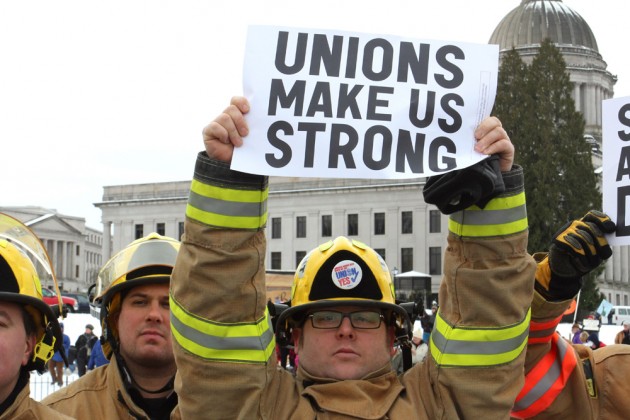

Likewise an astounding 45 percent of local government employees—including the heavily unionized occupations of teachers, police officers, and fire fighters—are unionized. This rate is considerably higher than the peak of private sector union membership (around 35 percent) in 1954, when the auto industry was in its heyday, American steel makers dominated the world market, many industries (airlines, communications, interstate trucking) were still regulated (and therefore protected from competition), and domestic manufacturers faced few global rivals. In heavily unionized states, such as California, New York, Michigan, and Illinois, the rate of union membership among employees of large municipalities approaches 100 percent—a phenomenon never observed in any private sector industry, even Detroit when the Big Three auto makers had a virtual monopoly in the domestic automobile market prior to 1970.

What are we to make of such a robust rate at a time when unions in the private sector are experiencing a freefall in membership? Well, obviously the government sector does not operate by the same rules as the private sector economy.

In a business, owners (or managers, when the enterprise is owned by shareholders) are subject to the discipline of the marketplace. Labor costs must be minimized to produce a competitively priced product at a profit. Accordingly, owners/managers are highly motivated to resist unionization, and will vigorously oppose union-organizing campaigns. Rarely if ever would a business voluntarily permit union organizers to recruit employees on the company’s premises, and certainly not when employees are on the clock.

If, despite the employer’s opposition, employees choose to be represented by a union, the owner/manager has strong economic incentives to resist excessive union demands in collective bargaining negotiations, hewing to reasonable wages and benefits. If one firm in a competitive industry has higher labor costs or less efficient work rules than other firms, it will be at a competitive disadvantage and will eventually lose customers and perhaps go out of business altogether.

Alas, none of these constraints exist in the public sector. In every important respect, governmental entities do not resemble businesses (which is why it is foolish to allow public employees to unionize and collectively bargain). Governments are monopolies that can and do compel people within their jurisdiction to pay for government services through taxes. The purchase of government services is, by definition, nonconsensual. Elected officials, who are the public sector counterparts of owners/managers, face no economic pressure to earn a profit, and do not have to worry about competing firms offering the same product for a lower price. There is no “discipline of the marketplace.” The only way governmental entities lose customers is when taxpayers move to another jurisdiction to escape a heavy tax burden, a decision that entails considerably greater transaction costs than merely changing brands.

Accordingly, government officials (unlike, say, the textile mill owners depicted in the movie Norma Rae) are largely indifferent to whether the people in their workforces unionize. They may even invite public employee unions to make recruiting presentations to newly hired workers as part of their orientation, while on the clock. Most important, when a union is chosen to represent government employees, elected officials are more inclined than are private sector employers to accede to demands for higher wages and benefits (especially benefits payable in the future, such as “defined benefit” pensions). The reason is obvious: they are negotiating with “other people’s money.” Elected officials may even agree to use taxpayer money to pay the salaries of union officers (who are also government employees) to perform union duties.

A truly pernicious aspect of public employee unions is that they use the union dues they withhold from the paychecks of government workers (and the “agency fees” they withhold from non-members) for political purposes. Public employee unions spend lavishly in political campaigns to elect candidates favorable to their interests. Unions such as the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, the Service Employees International Union, and the National Education Association are among the biggest political donors nationwide, and often dominate spending in local elections (especially school board races, which are “owned” by unions representing teachers). The vast majority of political contributions by public employee unions go to the Democratic Party. What happens then is utterly predictable. The elected officials endorsed and supported by public employee unions become enthusiastic advocates for union members, rather than the taxpayers.

Instead of the inherent tension between capital and labor in the private sector, which provides a sort of equipoise in collective bargaining, public employee unions essentially negotiate with themselves. The taxpayers merely pick up the tab. When existing revenue sources are insufficient to satisfy union demands, the unions simply lobby for tax increases.

As author Steven Malanga astutely noted a few years ago, government employee unions

have become the nation’s most aggressive advocates for higher taxes and spending. They sponsor tax-raising ballot initiatives and pay for advertising and lobbying campaigns to pressure politicians into voting for them. And they mount multimillion dollar campaigns to defeat efforts by governors and taxpayer groups to roll back taxes.

In the rare event that an elected official stands up to public employee unions, as Governor Scott Walker did in Wisconsin in 2011, the political backlash is epic, bordering on insurrection.

Collective bargaining in the public sector—sensibly opposed by President Franklin Roosevelt and by George Meany, head of the AFL-CIO—has succeeded in distorting the allocation of taxpayer-funded services to produce grossly absurd compensation for government employees (such as the BART janitor who earned $270,000 last year) and pension benefits so generous that they are a major factor in driving cities into bankruptcy. The National Labor Relations Act, or Wagner Act, was passed in 1935 to rectify the perceived “inequality of bargaining power” between capital and labor. Its proponents believed that because capital was organized in the form of corporations, labor needed the concomitant right to organize into unions. Whatever one thinks of this concept, it has no application to the process we have today, which allocates scarce taxpayer resources among competing demands—roads, schools, parks, and public safety.

The disastrous decision by states to allow unionization and collective bargaining by government employees—who, tellingly, are not covered by the NLRA—beginning in the 1960s created precisely what James Madison warned us against: the “dangerous vice” of faction. Public employee unions have become one of the most powerful interest groups in American politics, allowing government employees to dominate the taxpayers they supposedly serve. Until this imbalance is corrected—judicially or legislatively—local government in the United States will fall short of the ideal of popular sovereignty envisioned by Madison in Federalist 10.