The inconsistencies between Clausing 1.0 and Clausing 2.0 are indicative of an economics profession that has eschewed its own humble insights.

The Faulty Rhetoric of Income Stagnation

Both left- and right-wing attacks on liberalism (or “neo-liberalism”) highlight the claim that U.S. incomes have “stagnated” over the last generation for middle- and lower-income Americans. This ostensibly shows that the globalized market economy does not work for ordinary Americans. Politicians and groups advance a wide array of policies to respond to this problem. The thing is, though, that the data show wages have not stagnated but have increased significantly for all sectors of American workers over the last generation.

According to Congressional Budget Office data from 2016 (the most recent year available), incomes measured in constant dollars have increased by 33 percent for the poorest Americans—the bottom fifth—since 1979. Incomes have also increased by the same magnitude for the middle three-fifths of Americans. To be sure, incomes have increased by more than that for the top twenty percent of Americans. But the claim that the richer got richer while the poor and middle class also got richer has very different implications from the claim than that the richer got richer while the poor grew poorer and the middle class stagnated.

The news is even better, however, than the usual computations imply.

Of significance for the policy discussions in the upcoming presidential race—particularly among the Democrats—is that when incomes are calculated taking into account the tax, income, and social insurance policies that already exist, lower income groups have experienced even higher income gains over the last generation than indicated by the figures quoted above.

This is not a matter of evidentiary special pleading. An obvious way to measure the effectiveness of a policy intervention is to compare what outcomes would be with and without the given policy intervention. The evidence shows existing policies—tax, income, and social insurance policies—have already been remarkably successful at moving substantial amounts of income from affluent Americans to less affluent Americans. This moves the threshold for comparison. There is a huge difference between advocating for a set of policies because the rich have gained at the expense of the poor and middle class in a zero-sum game, and advocating for that same set of policies when everyone’s income has increased significantly.

So consider the data. The data come from the Congressional Budget Office’s report, The Distribution of Household Income, 2014, with the most recent update of data from 2016 released in July 2019.

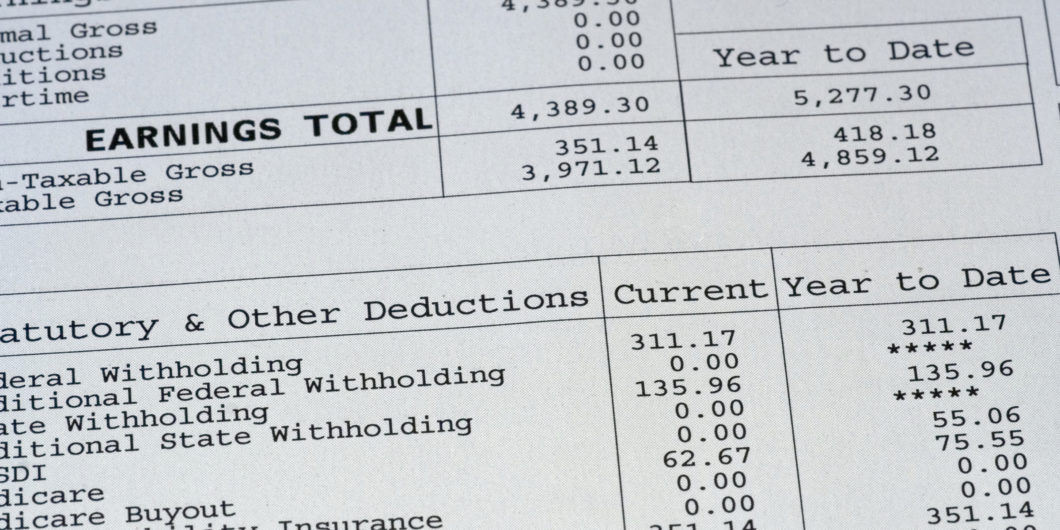

As an initial matter we can begin to understand the impact of taxes and transfers on income by looking at the most recent year for which there are data. In 2016, average income for the poorest 20 percent of Americans before taking account of taxes and transfers was $21,000. Taking into account tax policies, social insurance, and income transfers, average income for the poorest 20 percent of Americans was $35,000. That is, these policies increased the incomes of the poorest Americans by two-thirds over what incomes would have been without the policies.

Looking at the opposite extreme in income distribution, before taking these policies into account, average income for the richest 20 percent of Americans was $291,000. After factoring in taxes and transfers, average income for this group dropped to $214,000—a decline in income for this group of over 25 percent.

Comparing the numbers in a different way, the ratio of income of the richest fifth of Americans to the lowest fifth of Americans in 2016 was 13.86 before taking account of taxes and transfers. This ratio drops to 6.1 after factoring in taxes and transfers to incomes in both groups. Income disparity drops by over half by this measure when factoring in taxes and transfers paid out and received by the two extremes.

But we’re mainly interested in the oft repeated claim of “wage stagnation.” So what about income gains over time?

As noted above, the data show incomes for the poorest (and middle class) Americans increased by a third (33 percent) between 1979 and 2016 (in constant dollars) when looking at incomes before taking transfers and taxes into account. While this percentage gain does not reflect much on an annualized basis, it nonetheless represents a non-trivial increase over the entire time period. Incomes increasing by a third is not “income stagnation.”

But this is income gained before including the impact of taxes and transfers. According to the CBO data, when taking taxes and transfers into account, incomes for the poorest fifth of Americans increased by a dramatic 85 percent between 1979 and 2016. Incomes almost doubled during this time period for Americans in this group.

For middle class Americans (the three quintiles between the poorest fifth and richest fifth of Americans), incomes increased during this period by a third (33 percent) when not including taxes and transfers. They increased by almost half again (47 percent) when taxes and transfers are included.

The data do not support the claim that incomes stagnated in the U.S. over the last generation whether one includes taxes and transfers in those income numbers or not.

To be sure, incomes for the richest fifth of Americans increased by a whopping 101 percent during this same period. Irrespective, there is a big difference between increasing inequality when the rich get richer and the poor get poorer, and increasing inequality when the poor get richer, but simply don’t get richer at the same rate at which the rich get richer.

The income data considered with or without US tax, income, and social insurance policies are even more noteworthy when we consider the challenges the U.S. economy faced from a dramatically changing global economy, changes that critics of neoliberalism tend to ignore.

In something of an irony, American critics of neoliberalism tend reflexively to generalize the American experience onto the world. In doing so they incorrectly assume that if wages stagnated for American workers they also stagnated for workers throughout the world. I’ve discussed elsewhere why globalization implies workers in less developed countries gain even if American workers lose (here and here, hint: this phenomenon follows from some implications of the Stolper-Samuelson theorem). The reality, however, is striking: over the last generation a billion people in lesser developed countries have moved out of extreme poverty.

There are two implications. Firstly, the richest fifth of Americans have gotten richer because of increasing returns to capital. This is the flip side of increasing returns to labor in lesser developed countries. The remarkable thing is that the U.S. economy, in combination with existing redistributivist tax, income, and social insurance policies, has guaranteed that gains from globalization extend non-trivially even to Americans who own very little or no capital.

One little-observed consequence of this is that if the U.S. government had actually modified Social Security in the 1990s to allow workers to invest even a part of their Social Security withholding in private capital markets, the distribution of gains in the capital markets would have been much more widely shared during the last twenty years than they were.

Secondly, gains on par with the last twenty years for the richest fifth of Americans will not continue ad infinitum into the future. Globalization, with its different implications for American workers relative to American capital owners, has already changed the structure of the global economy. Potential gains going forward in 2020 for continuing globalization simply are not what potential gains were in 1979. In responding to globalization today, American politicians seek to close the proverbial barn door: The horses have already escaped. Critics of inequality also neglect that the rich are not gaining as much as it might seem in real terms relative to the increase in their nominal holdings: there has been massive sectoral inflation confined to the set of assets in which the rich compete against each other. This means the world’s rich are getting much less bang for their bucks than they used to, yet this change is pretty much confined to them. After all, it’s not as though capital gains results in the rich to bidding up the price of a McDonald’s hamburgers for the rest of us. Rather, they’ve bid up the prices of assets and “baubles” (Adam Smith’s word) against each other.

Finally, we should note that data from the last two years indicate that the tight labor market has finally begun reflecting itself in annually significant increasing wages for workers irrespective of taxes and transfers. With seemingly little future upside in capital markets given the huge run-up over the last ten years, this also implies a likely decrease in income inequality increases in the medium term.

The telling point about income, however, should not be lost in these weeds. Contrary to seemingly ubiquitous claims of income stagnation, the data show incomes for all American households increased substantially over the last generation. The data also show existing tax and transfer policies have in fact had their intended effect, with a substantial redistribution of income gains from the richest Americans to the poorest Americans. The data do not support a central economic claim of both left and right critics of neoliberalism.