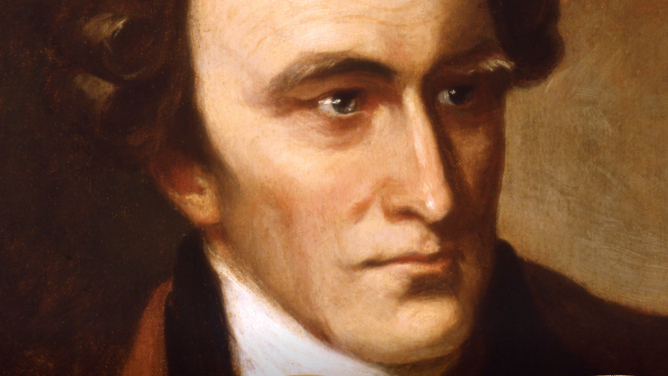

The Fiery Patrick Henry

In 1775, a 36-year-old named Patrick Henry swung the balance of the Second Virginia Convention with these words:

Why stand we here idle? What is it that gentlemen wish? What would they have? Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!

This impassioned statement, with its famous concluding phrase, convinced the delegates to commit troops to the War of Independence. Henry dominates the American imagination as a fiery orator and champion of independence.

Jurists and scholars interested in church-state relations often remember him for his proposed “Bill Establishing a Provision for Teachers of the Christian Religion” (1784), a purportedly illiberal scheme to create an established church that was defeated by a coalition of enlightened liberals and religious dissenters. But Henry—the sixth in the present series on the Founders’ debates on matters of church and state—was actually one of the most effective advocates of religious liberty during the formation of the new country. He was, moreover, far more prescient about the threats to liberty posed by the federal Constitution of 1787 than many Founders.

Born in 1739 in Hanover County, Virginia, Patrick Henry was baptized in the Church of England. His father and uncle held significant posts in the local parish, but Henry’s mother joined Samuel Davies’ Presbyterian church during the First Great Awakening. For many years, the young Henry drove his mother to the Davies meetings and listened attentively to the minister’s powerful preaching. This early exposure to evangelical sermons may have contributed to the development of his brilliant oratory.

Henry’s famous speech to the Second Virginia Convention bears the marks of this influence. In his book Reading the Bible with the Founding Fathers (2016), Daniel L. Dreisbach notes that he “lifted entire lines nearly verbatim from the King James Bible” and that the speech “reads like a lay sermon.” Scripture was Henry’s tool to meet a wide array of religious perspectives on common ground. While he was a lifelong Anglican, his beliefs and language were distinctly evangelical, and resonated deeply with the growing population of religious dissenters.

Henry first came to fame in a case opposing Virginia’s established clergy. In 1755, and again in 1758, the colony passed laws permitting citizens to pay their tithes in either tobacco or cash, at the rate of two pence per pound. The laws were disallowed by the king, and a minister of the established church sued for back payment of his salary. Henry launched a vigorous assault on such greedy clergy and convinced a jury to award the parson a mere penny.

His performance in this case, often referred to as the “Parson’s Cause,” contributed to launching Henry’s political career. As a member of the House of Burgesses, he helped author laws protecting pacifist Quakers and Mennonites from being compelled to serve in the militia. In 1769, he served on a committee that drafted a bill “exempting his Majesty’s Protestant Dissenters from the Penalties of certain Laws.” The bill failed, but Henry supported dissenting ministers in other ways, for instance defending them in court proceedings and, on at least one occasion, paying fines levied against them.

During the War of Independence, the Virginia Convention approved a resolution drafted by Henry that allowed Baptist ministers to preach to Baptist soldiers. In May 1776, the state adopted a declaration of rights, an important predecessor to the Constitution’s Bill of Rights. George Mason was its primary drafter, but Thomas E. Buckley, the best student of church-state relations in Virginia writing today, contends that Henry was almost certainly involved in crafting the declaration’s famous Article XVI, the final version of which reads:

That religion, or the duty which we owe to our Creator, and the manner of discharging it, can be directed only by reason and conviction, not by force or violence; and therefore, all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience; and that it is the mutual duty of all to practice Christian forbearance, love, and charity towards each other.

During debates over this provision, Henry proposed that the following language be added after “free exercise of religion”: “and therefore that no man or class of men ought to on account of religion to be invested with peculiar emoluments or privileges; nor subjected to any penalties or disabilities.” When questioned about the proposal, he denied that it was an attack upon the established church. Instead, at least in his mind, it simply extended the benefits afforded to this church to other denominations on an equal basis.

Given his longstanding support for religious dissenters, why would Patrick Henry propose an illiberal general assessment bill in 1784?

He believed in religious freedom, but like many other Founders, he considered Christianity essential to maintaining a healthy democracy. True religion, therefore, merited public support. Although the Church of England remained the established church, Virginia had not attempted to tax anyone (including Anglicans) to support it since 1775.

Henry’s proposed bill was aimed at reviving a wide array of churches. It taxed Virginians to support Christianity, but permitted them to specify which denomination would receive the taxes they paid. These funds would then be used to support “a minister or teacher of the Gospel” or to provide “places of divine worship.” Quakers and Mennonites were allowed to allocate the tax to their churches’ general fund. Tax payments not directed to a religious organization would be distributed by the General Assembly to “seminaries of learning.” This last provision arguably protected atheists and non-Christians (if anyone would admit to being either at this time) from being compelled to support a faith in which they did not believe.

The General Assembly postponed voting on the bill until 1785, and after a sustained campaign led by Madison a final vote was never taken. Instead, the legislature passed Thomas Jefferson’s famous “Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom” in 1786. There are good reasons to oppose even a multiple-establishment arrangement such as that proposed by Henry. However, and particularly in the context of the late 18th century, it is hard to make a convincing case that the proposal was illiberal or a threat to religious liberty.

Henry served as Virginia’s Governor for three more years, after which he was invited to attend the Constitutional Convention in 1787. To the surprise of many, he turned down the offer, reportedly saying that he “smelt a rat in Philadelphia.” Henry rightly suspected that some participants in the convention intended to consolidate the power of the national government and he was deeply concerned that revolutionary principles and freedoms would be lost in such a process. His vigorous opposition to ratification led him to champion the Anti-Federalist cause; once ratification became a sure thing, he was instrumental in arguing for amending the Constitution with the Bill of Rights.

Henry retired from public life in 1794, moving his family to his plantation in Charlotte County. Despite many offers to serve in prestigious positions, he remained out of politics until he was finally convinced to run for election to the Virginia House of Delegates in 1798. Three months before taking his post, Henry died on his plantation, leaving his property and slaves to his relatives and giving his wife the power to free them if she so chose.

Unlike many of his colleagues, Patrick Henry witnessed firsthand the suffering and dedication of religious minorities even as he experienced the rich tradition of the Church of England. His advocacy of religious liberty, including his support for the general assessment bill, is a testament to his deep respect for religious diversity. He should be remembered as an important promoter of religious liberty and religious equality, not as a supporter of an established church.